Two post-Soviet Caspian Sea sub-regions – Central Asia and the South Caucasus – have experienced different conflict scenarios. The South Caucasus has been embroiled in protracted, large-scale armed conflicts, while Central Asians have managed to avert a serious armed conflict, remaining largely peaceful in spite of local, short-term, small-scale clashes, and the existence of factors that may have led – and still may potentially lead – to a serious military conflict.

Armenia and Azerbaijan could have pursued a staunch European path similar to Georgia and Ukraine, but the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict appears to have represented an effective barrier for them. The Georgian war of August 2008 and the Ukraine crisis of 2014 showcased Russia’s uncompromising rejection of European and Euro-Atlantic orientations of post-Soviet nations. Moscow’s reaction provides a clue to understanding the diverging conflict scenarios in the Caspian sub-regions.

In theory, Central Asian countries can’t pursue a European path because of their geographical location beyond Europe. The geographical factor and its implications have played an important role in Central Asia’s significant political and economic dependence on Russia. For landlocked Central Asia, Russia is viewed much more favorably as opposed to other immediate neighbors – China, Iran, and Afghanistan by virtue of a range of political, security and economic considerations. Yet Russia, together with China and Iran, are effectively countering any Western presence in the region. Therefore, Moscow has remained relatively satisfied with Central Asia, which has contributed significantly to the lack of serious armed conflicts there.

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was the first violent dispute to break out in the former Soviet Union in late 1980s. Back then it was believed that it might cause a domino effect on other Soviet republics, including those in Central Asia, according to a declassified CIA file. Indeed, similar violent conflicts erupted later in Abkhazia and South Ossetia of Georgia, Transnistria of Moldova, and more recently, in Ukraine. But Central Asia has managed to avert a serious military conflict. Even now roughly three decades after the collapse of the USSR and the outbreak of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the South Caucasus, experts warn that territorial and border disputes with an ethnic dimension may turn out to be Central Asia’s “Karabakhs,” with even more dangerous consequences than the original. Following the annexation of Crimea, Western experts were worried about a “domino scenario” for Kazakhstan, as its northern regions that border with Russia are populated by ethnic Russian communities. But they miss significant factors contributing to the Nagorno-Karabakh and other conflicts in the South Caucasus, factors that are absent in the case of territorial and border disputes with an ethnic dimension in Central Asia. Those factors are, first and foremost, related to geography and hence the geopolitics of these two Caspian Sea sub-regions.

Central Asia Can’t Escape from Geography

A European orientation for post-Soviet nations often necessarily implies a Euro-Atlantic or transatlantic dimension, as Europe and the United States are closely interconnected through NATO, transatlantic free trade, and other arrangements. Therefore, a post-Soviet state’s orientation toward Europe is immediately perceived by Moscow as Euro-Atlantic, hence anti-Russia. This was the case for the Eastern Partnership launched by the EU to upgrade its relations with six former Soviet republics in the South Caucasus and Eastern Europe – Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. With the introduction of the Eastern Partnership, the EU drew a hard line in the Caspian Sea, with its western flank – the South Caucasus – being Europe and its eastern flank – Central Asia – falling outside the boundary.

The logic behind such division was due to geography. Central Asian nations are geographically located beyond Europe and have no perspective, even in theory, to become part of Europe with a slight exception of Kazakhstan, whose western part – around 10 percent of its territory – falls within the European continent. And Russia geographically and figuratively separates Kazakhstan and therefore, Central Asia from Europe. The republic of Cyprus was admitted to the EU in 2004 in spite of the fact that it is geographically located in Asia and therefore included in the Asian Group of the United Nations. Unlike Kazakhstan, which is separated by the Caspian Sea and Russia from Europe, Cyprus is in the direct neighborhood of Europe. Similarly, EU candidate state Turkey has only 10 percent of its territory located on the continent, though it is directly adjacent to Europe.

Geography determines not only the political but also the economic orientations of Central Asia. It is due to geographical location that Azerbaijan managed to build export pipelines delivering Caspian oil and gas through Georgia and Turkey to Europe while Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, the major Central Asian energy powers, have been deprived of such a luxury and remain dependent on the Russian route to gain access to European markets. Changing this would require a trans-Caspian infrastructure, but Russia together with Iran has managed to effectively block attempts to develop one. As a result, unlike the Central Asians, Azerbaijan and Georgia in the South Caucasus have achieved more economic and therefore, more political independence from Russia. In 2007, Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev suggested an idea of building a canal from the Caspian to the Black Sea in search of a less troubled access to Europe. This, as well as Astana’s interest in the proposed canal link between the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf, is symptomatic of Astana’s hopeless desire to break the curse of its landlocked geography.

A Snapshot of Disputes and Potential Conflicts in Central Asia

All Central Asia countries grapple with border and/or territorial disputes with ethnic dimensions to some degree. Negative Soviet legacies such as controversial definition and changes to borders, and practices of leasing lands such as pasture, water reservoirs, oil/gas deposits, and other facilities underpins various disputes in Central Asia, where dozens of contested enclaves exist. Furthermore, Kazakhstan is home to significant ethnic Russian populations, which could come to be involved in scenarios similar to that in Eastern Ukraine. Ethnic Russian communities’ share in the populations of the northern regions of Kazakhstan varies from 36 to 50 percent. These figures were much higher in early 1990s when the Soviet Union collapsed.

Uzbekistan-Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have experienced tensions due to territorial and border disputes with an ethnic dimension. At one point, the short-lived Independent Kazakh Republic of Bagys was self-proclaimed in a disputed village on the Kazakhstan-Uzbekistan border in 2001. These Kazakh-Uzbek disputes appear to have been resolved following a 2002 bilateral border agreement.

Uzbekistan-Kyrgyzstan

Uzbekistan has border disputes other Central Asian countries. Indeed, there are border disputes, unresolved territorial claims, and ethnic problems between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan also has border disputes with Kyrgyzstan centering on the Fergana Valley, particularly the Uzbek-populated city of Osh. Moreover, there are four enclaves within Kyrgyzstan that are Uzbekistan’s territory, and one within Uzbekistan that is the Kyrgyzstan’s territory. In 2010, bloody clashes erupted, killing hundreds of people, most of whom were Uzbeks, and displacing tens of thousands. 76 percent of the 1378 km-long Kyrgyz-Uzbek border has been demarcated so far and agreed to, while the remaining 324 km-long portion, including 58 disputed points, remains to be settled.

Uzbekistan-Tajikistan

Uzbeks constitute the largest minority ethnic group (15 percent) in Tajikistan, while Tajiks make up 5 percent of Uzbekistan’s population. The 105 km-long portion of the Uzbek-Tajik border where these minority populations live is subject to various territorial disputes. The Uzbek side has planted land mines along the border. Yet there are other issues and disputes related to fighting terrorism, and Tajikistan’s controversial Rogun Dam project. In particular, Uzbekistan’s iconic and historic Samara and Bukhara cities are home to large ethnic Tajik communities hence making them prone to ethnic tensions. But following the deadly 1992-97 civil war in Tajikistan, its claims to those cities has largely faded. And the civil war, which also involved ethnic minorities, ended with the involvement of Russia and Uzbekistan.

Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have accomplished the delimitation of around 519 km of their 978 km-long shared border. The remaining 459 km segment, which passes through densely populated lowlands, is subject to mutual claims and includes 58 separately contested sections. Tajikistan also administers two enclaves within Kyrgyzstan’s Fergana Valley region, which complicate the existing border disputes between the two nations. Indeed, the most complicated bilateral border negotiations involve the Fergana Valley, where a myriad of enclaves exist, and all three countries, which share it – Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan – have both historical claims to each other’s territory and economic interests in terms of its transport routes, rivers, reservoirs, and industries. Whatever happens in the Fergana Valley significantly affects all three of these countries in their economic, political, and religious spheres.

Central Asian Geopolitics

Russia Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov blamed the West, particularly the United States and NATO, for the non-resolution of conflicts in the South Caucasus, and for the breakout of the Ukraine crisis. Had legally binding norms been introduced to maintain an equal and indivisible security space in the Euro-Atlantic and Eurasia, then the conflicts such as the Nagorno-Karabakh and Transnistria would have been resolved long ago, according to Lavrov. “Our attempts to make those norms legally binding were rejected by Western nations” Lavrov said.

In other words, Russia wants legally binding obligations from the United States and its NATO allies that they won’t further expand into what is seen by Russia as its historical sphere of influence. This echoes President Vladimir Putin’s speech at the Munich Security Conference, which accused the West of betraying Russia by expanding into post-socialist Eastern Europe. He quoted the former NATO General Secretary Mr Woerner’s speech of May 17, 1990: “the fact that we are ready not to place a NATO army outside of German territory gives the Soviet Union a firm security guarantee.” Then, Putin popped up a rhetoric question: “Where are these guarantees?”

From the Russian perspective, in the absence of legally binding security guarantees from the West, the armed conflicts in Ukraine and elsewhere serve as a tool to block Western penetration into the post-Soviet South Caucasus and Eastern Europe. Central Asia is less prone to a similar Western presence, hence the lack of similar conflicts in Central Asia. The tool appears to be working, as the EU and NATO have made it clear that they wouldn’t be accepting new members with pre-existing conflicts within their territory. However, in another case, the EU has admitted the republic of Cyprus, which is divided into Greek and Turkish spheres. It doesn’t recognize the Turkish part – the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which is recognized and supported only by Turkey. But the point is that the EU treats Turkey and Russia differently. While the EU ignores its long-time NATO ally and EU candidate member Turkey’s concerns and interests regarding the Cyprus conflict, it is absolutely fearful, mindful, cautious, and conscious of Russia.

“The EU doesn’t have to have and doesn’t want to have any exclusive kind of space, but rather share the cooperation with others, avoiding geopolitical games in the region [Central Asia],” said Peter Burian, the EU Special Representative for Central Asia. The statement shows that the EU is being careful not to antagonize Russia in Central Asia. Due to this cautious approach, along with Europe’s emphasis on human rights, rule of law, and democracy, Central Asian leaders tend to keep their distance from the West. This is a comfort to Russia as well as China, which are not renowned for promoting those values.

The Council of the EU’s EU Strategy for Central Asia concludes that relations will flourish or flounder on Central Asian countries’ commitment to undertake reforms to strengthen democracy, fundamental freedoms, the rule of law, independence of the judiciary, and to modernize and diversify their economy. “There’s a disconnect between the EU’s (and other Western nations’) stated strategy goals and what has transpired in the region over the past 25 years,” according to Catherine Putz. Central Asian leaders don’t appear to be very enthusiastic about issues concerning reforms, rule of law, democracy, human rights, etc. For instance, presidential changes have come either through death (Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), revolution (Kyrgyzstan, 2010), civil war and the involvement of external actors (Tajikistan), or no change at all in the case of Kazakhstan, where communist era leader Nursultan Nazarbayev survived the collapse of the Soviet Union and has ruled since 1991.

Following the Andizhan events of May 2005, Uzbekistan sought better relations with Russia and China, who supported Tashkent’s handling of the unrest, in contrast to the United States’ and other Western countries’ criticism of it. In 2005, Uzbekistan, the once-partner of the West, closed its US military base, which was established in 2001, and quit the Washington-backed GUAM grouping of post-soviet nations including Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Moldova.

Central Asia is in the same neighborhood as Iran and Afghanistan. Neither Central Asian elites nor ordinary populations are inclined or sympathetic to them. As contrasted to other neighbors, they find Russia more suitable. Russia offers a huge market for labor immigrants and agricultural products. In the case of Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, Russia is also the major transit country to export their oil and gas to European markets. Moscow is a crucial security partner to fight religious extremism and counter cross-border inflows of violent extremists from Afghanistan and elsewhere. For instance, the 1280km-long Afghan-Tajik border is patrolled by Russian military, who were originally stationed in the country due to the Tajik civil war, and then were reassigned to protect the border with Afghanistan, where sizeable numbers of ethnic Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Turkmens live. Central Asian nations have largely refrained from accepting their fellow ethnic refugees from Afghanistan mainly due to security concerns. They see a potential security threat in refugees from Afghanistan.

Finally, there is the Turkish factor. Turkey and Central Asian countries, with the exception of Tajikistan, are ethnically and linguistically connected. On top of that, Turkey is a long-time NATO member and closely tied with Europe in spite of the current tensions between Ankara and its NATO allies, and ongoing rapprochement with Moscow against the backdrop of the Syrian civil war. Yet Turkey is geographically distant from Central Asia, unlike the case of the South Caucasus, where Turkey is an immediate neighbor and is the closest ally of Azerbaijan and maintains a strong partnership with Georgia.

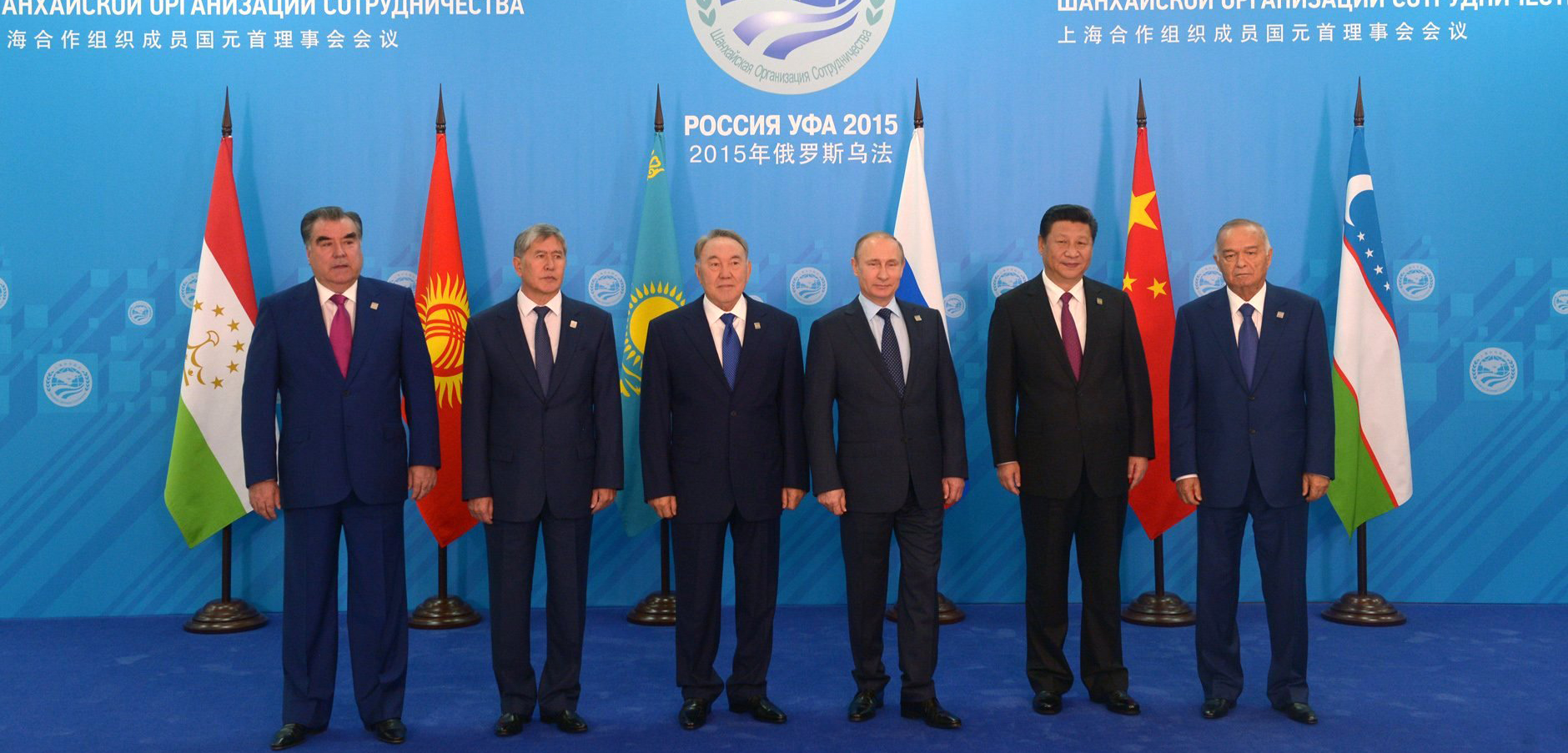

Russia along with China is seeking to prevent a US presence in Central Asia, and they view the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) as serving the purpose of counterbalancing US influence and thus preventing its domination in the region. Another regional power, Iran, is also aligned with Moscow and Beijing to avert a US and NATO presence in the region. In fact, the triangle of Russia-China-Iran has largely succeeded in doing so. Tehran’s role is particularly striking in keeping the Caspian Sea clear of a Western military presence.

Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are the major countries in Central Asia in military, economic, territorial and population terms. And there is a perennial rivalry between Astana and Tashkent over regional primacy. This rivalry was a major reason for fading of the idea of a Central Asian Union, which had originally been proposed by Kazakhstan’s Nazarbayev in 2005 as a model for closer regional integration. “We have a choice between remaining a supplier of raw materials to global markets and waiting patiently for the emergence of the next imperial master, or to pursue genuine economic integration of the Central Asian region,” he said.

The Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) stands as another attempt at regional integration, but the regional bloc still lags in membership. Border and territorial disputes with Kyrgyzstan are the major obstruction to Tajikistan’s accession to the EAEU. Turkmenistan has declared itself a neutral nation and instead joined the Non-Alignment Movement, while Uzbekistan has so far refrained from joining either group.

“Russia has a vested interest in seeing regional border disputes resolved peacefully but many also argue that Moscow has at times been keen to take advantage of a manageable level of turmoil in Central Asia as a means to pull the CIS states back more closely into its sphere of influence” according to a report from the International Crisis Group. The Kremlin-tied Russian media makes far fewer negative mentions of Central Asia as compared to adversarial references to the Baltics, Eastern Europe, and South Caucasus regions. This is indicative both of Moscow’s relative satisfaction with the circumstances surrounding Central Asia and its priority to focus on Eastern Europe and the South Caucasus. The implications of Central Asia’s geographic location appear to be reassuring Russia. This reassurance is further reinforced by changing perceptions of the West in the post-Soviet space due to circumstances in the South Caucasus and Eastern Europe. Indeed, European inaction in particular and Western toothless reaction in general as combined with the Russian actions regarding the Georgian events of August 2008 and Ukrainian events of 2014 has considerably discredited the reputations of the EU and NATO in the perceptions of post-Soviet countries, including Central Asians. This bolsters Russia’s ability to project its power in the region as Central Asians are absolutely cautious about closer Western involvement in the region. A major downside of this trend is that authoritarianism will likely persist in Central Asia in the foreseeable future. The upside is a reduced risk of border and territorial disputes turning into serious military conflicts.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.