Academics, marine biologists, retired military personnel, senior State Department officials, and NGOs continue to add their voices to a growing Washington chorus on the complex and challenging South China Sea (SCS) territorial disputes. At a recent Johns Hopkins Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies Program, “Promoting Sustainable Usage of the Oceans–Security, Collaboration and Development,” The Maritime Alliance in collaboration with Foreign Policy Institute, addressed a range of topics, including promoting sustainable ocean development, global collaboration for sustainability and security and development in the South China Sea.

As one of the SAIS presenters, along with distinguished University of Miami marine biology professor John McManus and retired US Marine Corp. Lt. General Wallace Gregson, we took aim at China’s continued unsustainable fishing practices and reckless reclamation in the Spratly Islands.

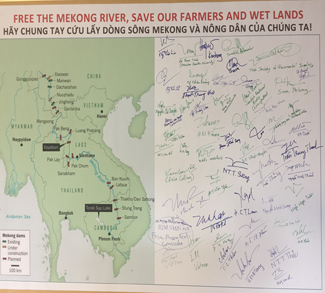

Because this region is one of the most important large marine ecosystems in the world, rich in marine living resources and a mainstay for the livelihood of the local community in SCS nations, policyshapers are taking note of the necessity to create more marine protected areas.

Professor McManus has been lobbying for over 20 years through scientific papers and conferences like this one in Washington for marine protected areas, especially in the Spratlys.

“Vietnam, a claimant nation, already has marine reserves, so this involves extending this practice to the Spratly area. It is usually difficult to institute conservative harvest and protection practices when there is the threat of competition from outsiders. Vietnam stands to lose a great deal if the current situation continues and results in a general decline in fisheries across the South China Sea,” claims McManus.

The protection of the marine ecological environment is a global issue.

Of course, talks of cooperation and conciliation are overlapped by constant intimidation and unlawful engagements over resources and land claims. In our panel discussion, the speakers affirmed the immediate need for a more sustainable use plan that would freeze current claims on the Spratlys and establish an international peace park.

The Philippines and Vietnam have time and again chosen to look at the South China Sea as a sea that binds rather than divides claimant nations by trying to promote cooperation on common interests.

Marine scientists, including those from Taiwan, believe that a carefully managed park will safeguard the declining number of fish species and to protect valuable coral reefs. McManus, along with Dr. Kwang-Tsaou Shao and Dr. Szu-Yin Lin of the Biodiversity Research Center from Academia Sinica, Taiwan, co-authored a 2010 paper advocating the establishment of an international peace park in the South China Sea, which would “manage the area’s natural resources and alleviate regional tensions via a freeze on claims and supportive actions.”

According to McManus, China reclamation constitutes the most rapid rate of permanent loss of coral reef in human history. As an environmental policy journalist, I have written often on the South China Sea’s environmental security. Environmental scientists say the dangers are increasing as the conflicting sovereignty claims heat up between China and eight East Asian nations bordering one of the world’s most strategic maritime routes, which boasts an irreplaceable ecological harvest of atolls, submerged banks, islands, reefs, rock formations and 3,000 species of fish.

The protection of the marine ecological environment is a global issue. The ocean’s sustainability is vital for all life. The challenges in this fragile and interconnected marine web are profound, including climate change, destruction and damage to marine ecosystems, loss of biodiversity, and the degradation of the natural environment through overfishing.

In 2002, the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), which the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei are members of, and China signed a declaration of conduct in the South China Sea and committed to pursuing efforts to “resolve their territorial and jurisdictional disputes by peaceful means, without resorting to the threat or use of force.”

Nevertheless, China’s actions have been anything but compliant.

Policyshapers are interested in exploring alternatives and so the marine protected area is now gaining more currency. The suggestion that sovereignty claims might be temporarily suspended requires much more than Wilsonian beliefs. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines peace parks as “transboundary protected areas that are formally dedicated to the protection and maintenance of biological diversity, and of natural and associated cultural resources, and to the promotion of peace and cooperation.”

There are arguably many stellar examples:

The Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park created in 1932 between Canada and the United States. This agreement led to collaborative research, eco-tourism, and increased partnerships.

The Red Sea Marine Peace Park established in 1994 between Israel and Jordan in the northern Gulf of Aqaba. This pact led to normalization of relations and fostered coordination of marine biology research on coral reefs and marine conservation.

The Torres Straight Treaty signed in 1978 between Australia and Papua New Guinea resolved, after a decade of negotiations, numerous political, legal and economic issues.

The Antarctic Treaty forged in 1959 is an excellent example of a multilateral peace park and solidified collaborative scientific research and conservation practices.

The Joint Oceanographic and Marine Scientific Research Expedition in the South China Sea, a cooperative bilateral exercise between the Philippines and Vietnam initiated in 1994 and followed up with three more until 2007 covered the southern part of the South China Sea.

Since Washington acknowledges the transnational and multilateral nature of South China Sea environmental issues, ASEAN is the logical institution in the region to provide a framework and to champion environmental security in Southeast Asia. China’s unilateral actions in their dangerous reclamations violate the terms of the ASEAN-China Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC-SCS). Unfortunately, China’s attack on the ecological heart of Southeast Asia has not resulted in any condemnation from ASEAN.

Marine scientists like Dr. Edgardo Gomez from the Philippines and Dr. Nguyen Chu Hoi in Vietnam know that healthy coral reefs provide food, storm protection, and cultural identity to coastal communities. The challenge for Washington and the world is to offer a solution to protect these rain forests of the sea.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.