With twenty percent of the world’s population, China has only seven percent of the fresh water. Yet the country controls crucial fresh water sources needed by three billion people in Asia. And it will not share it.

As Chinese troops swept into Korea in 1950, Mao Zedong was seizing control of Xinjiang and Tibet, regions that encompass the headwaters of six rivers flowing from the mountains of Tibet, and are collectively depended on by nearly fifty percent of the world’s population.

Two of the rivers, the Yangtze and the Yellow, are critical to China, with 580 million Chinese dependent upon the Yangtze alone. The Yellow River has in the past 70 years lost nearly 90% of its flow, a rate of decline that is symptomatic a brewing national crisis.

Over the past quarter century, rapid industrialization and urbanization in the People’s Republic of China has resulted in 28,000 bodies of surface water disappearing. Around 70% of these water resources have been directed to agriculture, and 15% to resource extraction and industrial processes. If new sources cannot be found, resource industries, such as rare earth processing that uses a great deal of water and manufacturing, will suffer.

Mao Zedong was well aware in 1952 of his country’s water distribution issues, with 80% of the PRC’s water resources in the south and two thirds of its agricultural production in the north. To redistribute the water, he advocated what has now become a $70 billion canal system. The South-to-North Water Diversion project is transferring water through a 1,200 kilometer canal system to the Beijing region; but additional water is simply serving as a stopgap until other sources can be secured. Late in the game, the Chinese government has come to realize that they have been squandering scarce resources by allowing extensive pollution from agricultural run-off and industrial waste. Half of the population does not have access to safe water, with 90% of cities depending on polluted underground water. Fifty cities, including Beijing, are experiencing land subsidence due to the exhaustion of these underground water sources.

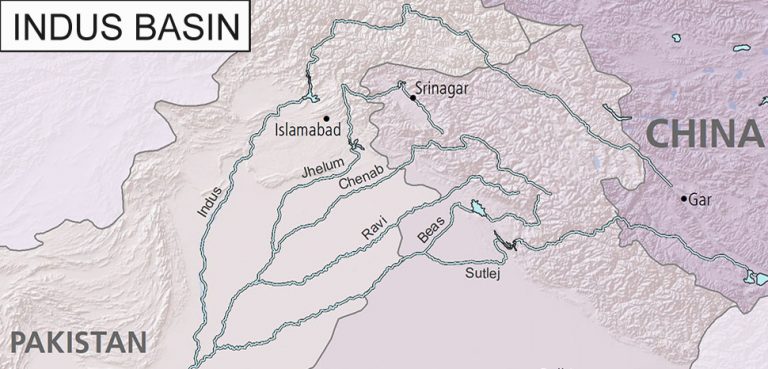

Former premier Wen Jiabao, said that “the very survival of the Chinese nation is threatened by lack of a water supply.” Already, China is seeking a solution by tapping the flow of four major rivers that supply nine bordering countries: the Mekong, the Brahmaputra, the Indus, and the Ganges. Eleven dams have been constructed on the Mekong. Seventy million people in Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam rely upon the river. China controls the headwaters and shows little interest in its policy impacts downstream. By the time the river reaches Vietnam, it is scarcely more than a trickle.

Next on the agenda is the Brahmaputra. In August, Jiacha Dam, the second hydroelectric facility, was completed. Future dams are expected to begin directing water through alternate channels to replenish the Yellow River.

With only 3% of the Indian population dependent upon the river, its real value is political. India is developing the river in Arunachal Pradesh along the Tibetan frontier. The 90,000 km2 territory is claimed by China as a part of southern Tibet, and Beijing objects to any project that indicates that Delhi intends to remain.

Delhi has accused China of supporting a fifth column in the form of a local separatist movement, the United Liberation Front of Assam. The long-neglected and impoverished region is linked to western India by a narrow corridor known as the ‘Chicken’s Neck.’ If China were to sever the corridor, India would lack the means to reclaim its territory and many of the ethnic minorities there would not necessarily oppose separation from the rest of India.

More so than India, China has invested in a rail and road network in the high mountains, and is backing up its land-based forces with aircraft from local air fields. A skirmish in the Galan Valley near the Chicken’s Neck in June, in which 20 Indian soldiers were killed, is a warning to Delhi over its construction of a new all-weather highway through the territory. China seeks to emphasize that it is the party which sets the rules of engagement.

India faces an underground movement in Assam; Chinese forces with their more advanced weaponry near the Galan Valley; Pakistan ground units along the Kashmir frontier; as well as a Pakistan-supported insurgency inside India-controlled Kashmir. Should there be a coordinated assault by the Chinese and Pakistani armies, India would likely face another defeat at the hands of the Chinese, as happened in 1962 when Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru asked President John Kennedy for military assistance. The collapse of the Indian army was so thorough that it appears as though the PLA would have pushed all of the way to the Bay of Bengal had Washington not intervened. Aid from the U.S. and from the UK rescued India, although China did keep 40,000 km2 of territory in Ladakh and maintains further claims to this day.

Faced with an economic contraction and a far more powerful China, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, after hesitating for several years, has decided to join the Quad, an informal alliance with Japan, the U.S., and Australia, in order to deter China. Alone, China views India as an inferior rival. However, an India acting in alliance with the U.S. changes the equation and poses China with a dilemma: Is the need to acquire water worth the risk of a war with nuclear-armed India and, potentially, the United States as well?

Chairman Xi Jinping is the man with the answer.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any institutions with which the authors are associated.