For all the defining moments in history post-“the long nineteenth century,” spanning to the unipolar moment‘s recent end, the advent of the United Nations (UN) has perhaps meant more to the cause of international peace than any other. After all, a corrective to the short-lived qua ill-fated League of Nations, the UN was formed in the crucible of peace.

There is much in its storied history to support this view. But this framing has its limits, especially as the liberal international order has come under unprecedented strain over time.

Alas, having regard to its central aim of tamping down and resolving international conflicts/crises, the UN’s ability to serve as a cornerstone of international cooperation is currently undermined in at least two ways.

The first centers on the nature of the crises themselves. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres readily admits, this moment of international politics is “marked by increasingly complex crises for our world.”

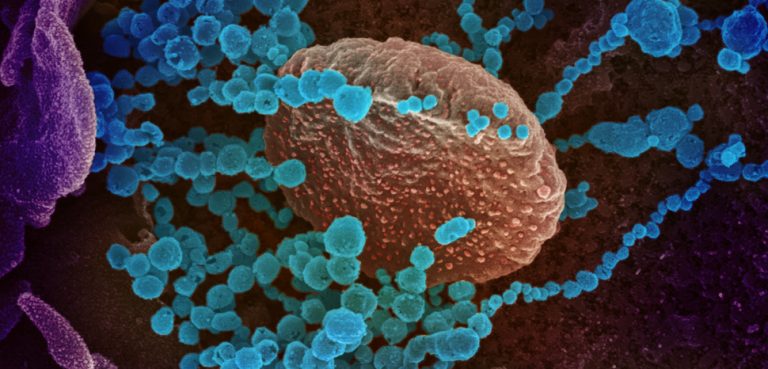

In fairness, in some instances, this is through no fault of its own. A case in point is the COVID-19 pandemic’s “deeply negative impact on SDG progress.”

Regardless, in the early goings of this post-unipolar moment-related conjuncture, the UN’s risk exposure-cum-profile has risen exponentially. A centerpiece of that risk is the emergent global transition to a multipolar system, which hinges on and is driven by great-power competition.

Beyond that, and secondly, as Guterres also underscores, “geopolitical mistrust” is at an all-time high. This is because great-power competition is in full swing, widening East-West and Global North-Global South divisions.

The main architects, along with their proxies, of unfurling post-Western-oriented geopolitical dynamics have seen to it that great-power engagement is in the rear-view.

Inasmuch as they are geopolitically significant moments in their own right, the Gaza and Ukraine wars are emblematic of those broader divisions, which are also unsettling the extant international order.

Just how those conflicts further take shape and the implications arising thereof will have a bearing not just on the UN’s 193-strong membership, but also on its fortunes going forward. This is playing out in a context where the UN, straining under the weight of a mismatch of organizational functionality and aspects of the shifting geopolitical realities in question, is already at a tipping point.

The UN Security Council, which is caught up in and is seemingly adding to international system-level dysfunction, is a prime example.

In the circumstances, the P5 UNSC members can ill afford to continue to pay lip service to UN reform.

Given the stakes involved, small states, such as those of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) bloc, also have a lot riding on UN reform. That’s how they see it; not least because their leaders have expended political capital on the matter.

Indeed, recognizing the wider, security-related impact of these conflicts, they have adopted a highly participatory approach to international diplomacy of the hour as regards the Gaza and Ukraine wars, which are on center stage in international relations. (That said, as part of their attendant diplomacy, CARICOM member states have pitched their reactions differently vis-à-vis the aforesaid conflicts.)

Yet it is important to recognize that, also in their view, such diplomacy will only achieve so much.

In that respect at least, for crises-related diplomacy to be given effect in ways that matter, UN organs like the UNSC must be fit for purpose vis-à-vis today’s (security) realities.

For all the world body’s success since it first opened its doors on October 24, 1945, then, such UN-related staples as the Security Council continue on as a vestige of a bygone era, whose architects have long since passed on. And as is often the case in such large organizations, owing to their path-dependent design, institutional inertia sets in. Given that its roots run deep through history, the UN is especially prone to such a state of affairs.

The UN’s roots can be traced to a series of high-level conferences, held in the 1940s, which took place at the behest of Allied powers’ statesmen of the day, who were committed to and vested in crafting the institutional contours and systemic orientation of the post-war international order.

But first, they had to craft a way out of the war. The Yalta Conference and the Potsdam Conference were crucially important in that regard, constituting final steps in the Allied powers’ efforts to bookend the war.

By May 1945, Germany had unconditionally surrendered. This resulted in an Allied victory over that leading Axis power, ushering in the “zero hour” or “Year Zero.”

Yet, this marked only the first of two hard stops to the war.

The final one came later on in 1945, stemming from Japan’s unconditional surrender. This occurred in the wake of the United States’ atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but also—thereafter—the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on this second of the two foremost Axis powers.

Given the sheer scale of that war’s devastation, 19th century German dramatist Georg Büchner’s outlook on mankind was likely never far from the minds of statesmen and diplomats of the day; i.e. mankind is held beneath the “hideous fatalism of history…[and] human nature [has] a terrible sameness, in human circumstances an ineluctable violence vouchsafed to all and to none.”

In hopes of distancing humanity from war and its uglier side, thereby charting a way forward towards some semblance of peace in the anarchic international system, yet another monumental conference took place to set the stage, as it were, between April 25, 1945 and June 26, 1945. This United Nations Conference on International Organization—held in San Francisco, California—brought together delegates of 50 governments.

Informed by the work of other, previously-held high-level meetings and outcome documents from the same—including The Atlantic Conference & Charter (1941)—this Conference (dubbed the San Francisco Conference) unanimously approved, inter alia, the UN Charter and the Statute of the International Court of Justice, thereby establishing the UN.

Today, for the reasons outlined above, one may well ask—is it time for a San Francisco moment 2.0?

After all, the UN is struggling to navigate towards a resolution to the Gaza and Ukraine wars, which raise the ante in terms of global insecurity. The UN is at a crossroads, then, and all the more so because of the Gaza and Ukraine wars.

All things considered, notwithstanding the state of the world, it is less likely now that such a moment will (meaningfully) see the light of day. In short, in this geopolitical moment, the grand sweep of great-power competition is too much of an encumbrance to that end.

It would take a leap of the imagination to believe otherwise.

But that should not hold back the good work of those who are contributing to efforts to advance on the UN’s future development and, in this regard, UN reform. To paraphrase ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, change is inevitable.

It is also worth noting, Rome was not built in a day.

But it is also the case that, as some of the world’s most intractable conflicts and crises continue to spiral unabated—putting virtually all of the international community in peril, as the UNSC is hamstrung by “strategic competition between the United States, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and the Russian Federation”—the UN and its membership do not have all the time in the world.

Something has got to give.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.