Summary

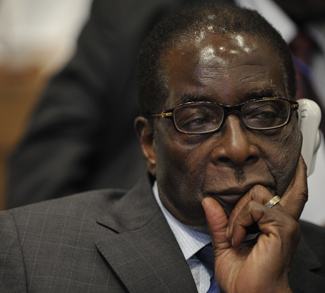

The Zimbabwe coup has been a peculiar one from the onset. First the military seized parts of Harare, insisting that it wasn’t staging a coup but rather was targeting ‘criminals,’ one of which happened to be sitting president Robert Mugabe who was subsequently placed under house arrest. Then this weekend events took another turn for the bizarre when Mugabe was allowed to address the nation under the assumption he would step down and end his 37-year reign with dignity. Of course he didn’t, instead doubling down on his constitutional authority over the troops that had turned their guns on him. Now the deadline for Mugabe to resign has passed, and impeachment proceedings will be initiated by the ruling Zanu-PF party, supported by the opposition MDC-T.

Mugabe’s unwillingness to play ball with the coup plotters is not terribly surprising given the defiance that characterized his leadership style. However, his gambit will surely reverberate as Zimbabwe heads into the unknown of the post-Mugabe era.

Impact

The two central figures in the coup – former vice president Emmerson Mnangagwa (‘the Crocodile’) and General Constantino Chiwenga – have close ties to the embattled president, which explains the soft approach the army has adopted in taking power. Put simply, both Mnangagwa and Chiwenga want nothing more than Mugabe to go quietly into the night so that they can inherit the same Zanu-PF apparatus that helped Mugabe rule the country since independence.

Conflict between Mugabe and the coup plotters opens the door for splits within the Zanu-PF, which threatens to weaken the party’s hold on the Zimbabwean political mainstream. It’s also extremely difficult for Mnangagwa and Chiwenga to bring an uncooperative Mugabe to heel by airing out the president’s dirty laundry in public, because both men were complicit and/or actively participating in many of Mugabe’s authoritarian exploits.