Building bases

Recent satellite imagery released by the United States (US) satellite imagery company BlackSky depicting the Ream Naval Base in Cambodia, which is funded by China, has garnered significant attention from the US government. The construction of the naval base in Sihanoukville, situated on the Gulf of Thailand, was previously regarded as a mythical notion. Nevertheless, reports based on satellite imagery have the potential to offer compelling evidence suggesting that China’s naval base is nearing completion. Nevertheless, China’s pursuit of establishing additional bases is not limited to this specific case. Based on an assessment made by the US-based research institute, AidData, authored by Alex Wooley, Sheng Zhang, Rory Fedorochko, and Sarina Patterson, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Bata in Equatorial Guinea, and Gwadar in Pakistan are the three most likely locations for a Chinese naval base to be established between 2025 and 2030.

The shortlist comprises a total of eight prospective locations where China could potentially establish naval bases within the upcoming two to five years, with four of these being situated in Africa. These locations are Kribi, Cameroon; Luganville, Vanuatu; Nacala, Mozambique; and Nouakchott, Mauritania. China has made significant investments in ports, port facilities, and infrastructure situated in West and Central Africa, as well as the Atlantic region. The choice of nomenclature holds significance as it seemingly avoids the utilization of the term “base,” which implies a temporary though aggressive aim, in favor of employing diplomatic yet deceptive terminology.

Hence, it is plausible to argue that the Chinese investments, intentional use of non-military terminology when discussing its prospective facilities, and the evident advancement or near-completion of construction projects could be interpreted as indications of Beijing’s strategic ambitions in maritime affairs. Consequently, these developments may pose a challenge to the dominant position of the US, contributing to the emergence of a security dilemma.

Strategic maritime ambitions

China’s pursuit of multiple bases, including one for porting warships on Vietnam’s southwestern flank, is indicative of its strategic ambitions. In recent years, Beijing has demonstrated a proactive approach in augmenting its military capabilities by establishing ports in strategically important areas. Several noteworthy examples can be identified, such as the Hambantota International Port in Sri Lanka, which necessitated a substantial investment of approximately US$2.18 billion, as indicated by data sourced from AidData. Additionally, the Autonomous Port of Kribi in Cameroon demanded an investment of approximately US$1.30 billion, while the Bayport Terminal at Haida Port in Israel required an investment of approximately US$1.25 billion. Lastly, the Port of Kaia in Angola necessitated an investment of approximately US$1.10 billion. China has strategically positioned military installations in several locations, including Oman, Djibouti, Kenya, Tanzania, and the Seychelles, alongside its territorial presence in neighboring regions.

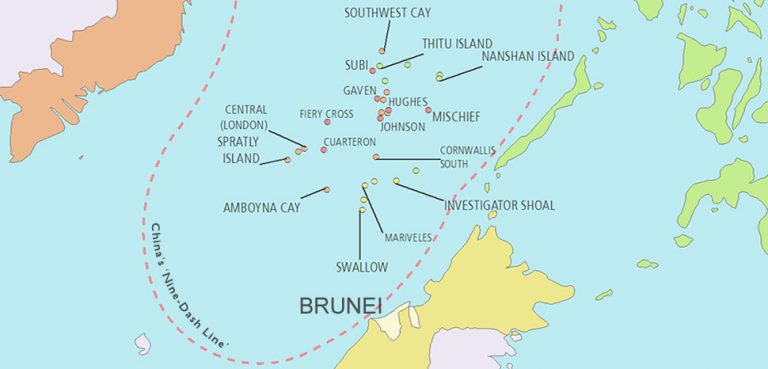

If the visual representations of the Ream Naval Base are indicative of a positive stance towards the enlargement of the pier, which would accommodate large warships, it is improbable that the harbor is intended solely for transport vessels. Upon its completion, the port would serve as a valuable addition to China’s maritime capabilities, effectively expanding the operational range of its naval vessels and giving the PLAN direct access to the Gulf of Thailand while complementing the PLA’s existing bases in the South China Sea (SCS). The ports can additionally provide concealment for PLAN warships.

The development of Beijing’s strategic port network can be perceived as a collection of valuable assets encircling India, a regional power contender, facilitating connectivity between the PLAN and coastal areas that extend well beyond China’s immediate proximity. The network plays a pivotal role in enhancing the capabilities of the PLAN, thereby potentially facilitating its transformation into a formidable blue-water military force with the ability to dock and resupply in remote locations.

The construction of additional ports, however, presents novel challenges for nations beyond the borders of India. The parties involved in the SCS dispute have been required to adapt to the existence of Chinese military installations that have the capacity to accommodate missile submarines and offensive military aircraft in previously unoccupied regions. In the foreseeable future, it is anticipated that the US will witness the introduction of PLAN warships in areas where their presence has hitherto been absent. The feasibility of this scenario can be attributed to the increasing number of bases capable of accommodating PLAN warships, as well as the projected growth in the size of the PLAN. Rear Admiral Michael A. McDevitt (retired) anticipates that by 2035, the PLAN will possess around 270 warships capable of operating in open waters, surpassing the size of the US Navy.

Challenging US hegemony

There has been frequent assertion in recent years that China’s expansive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a strategic maneuver aimed at undermining the prevailing dominance of US hegemony in China’s neighboring areas, and its ambitious objectives appear to be rooted in establishing strongholds in regions that would provide significant advantages for its military capabilities. China’s strategic focus on Central America, Africa, and the Arctic region exemplifies this concept.

Washington discusses China’s ambitious pursuit of global power with unbridled expression, specifically alluding to Xi Jinping’s BRI as the guise under which this endeavor is unfolding. While the BRI may initially seem to be primarily driven by economic considerations, it is crucial to recognize that it also encompasses national security objectives and aspirations. The BRI has played a crucial role in facilitating the establishment of strategically important docks and ports by China, which are vital for supporting its naval operations. The negotiations between Beijing and Chile regarding the construction of a port in Punta Arenas would potentially grant China the opportunity to establish a presence in Antarctica.

China has made significant financial investments in José Petroterminal in Venezuela, amounting to US$441 million, and in the Port of Santiago de Cuba, with an investment of US$133 million. These financial commitments have provided China with the strategic advantage of establishing a presence and the ability to redeploy PLAN warships in close proximity to the mainland US. The ability of China to dock its warships in close proximity to the US, similar to Russia’s recent docking of the training class ship Perekop in Havana on July 11, 2023, suggests a significant challenge to and a potential erosion of the US’s long-standing Monroe Doctrine.

The necessity of these ports for China’s trade operations is questionable. Instead, they fulfil a more significant role, specifically providing a means of securing berthing for naval vessels in regions where US military supremacy has been widely accepted.

China’s strategic interests in port development beyond Cambodia encompass regions where it is highly improbable for US dominance to be relinquished. Historically, South America and the Western Hemisphere have conventionally been perceived as the sphere of influence or “backyard” of the US. This perception was notably challenged by the Soviet Union in October 1961, during a tense period of approximately two weeks known as the Cuban Missile Crisis or the October Crisis, characterized by nuclear anxieties. The Western Hemisphere has also traditionally been regarded as the domain of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), in accordance with the tenets of Cold War ideology.

Do these measures constitute a fundamental element of Beijing’s strategic plan aimed at realizing Xi Jinping’s vision of the “great revival of the Chinese nation”? Throughout the annals of human history, opposition to dominant power structures has consistently manifested as a recurrent phenomenon. During the period spanning the late 15th and early 16th centuries, Portugal emerged as a prominent global leader, while Spain emerged as a formidable challenger in the global arena. During the late 16th and early 17th centuries, France emerged as a formidable contender to the Netherlands in its pursuit of global leadership. The Dutch Republic underwent a notable decline due to a range of challenges posed by France that impacted its security and economic prosperity. During the late 17th century to early 18th century, the British Empire faced substantial regional and global challenges to its dominance, primarily from France at first, followed by Germany. From the early 20th century until 1945, the Soviet Union emerged as a formidable contender to the US in its pursuit of global leadership.

Immanuel Wallerstein’s neo-Marxist framework posits that the US underwent a phase of pronounced hegemonic ascendancy until 1967, after which it entered a subsequent phase of decline that has persisted until the present. Chinese naval expansion, facilitated by the acquisition of new ports, can be interpreted as a reflection of historical trends in which emerging powers challenge established hegemonic powers. For example, China’s commercial activities in the Indian Ocean point to investments that may foreshadow China’s intention and capability to be able to operate high-end military missions. The allocation of Chinese resources towards port infrastructure development may potentially yield significant military capabilities. These investments include naval deployments that exceed the necessary capabilities for countering piracy or engaging in humanitarian activities. They also involve the development of advanced platforms for gathering intelligence at sea against state adversaries. Additionally, efforts are being made to enhance the resilience of logistics networks that play a crucial role in conducting operations during times of conflict.

A nascent security dilemma

The portrayal of an entity as a military threat by the US government is likely to result in the development of policy responses that align with this perception. This assertion posits that the existence of a military threat is substantiated by its interpretation, thereby implying that the process of military escalation has commenced.

The prevailing issue concerning perception lies in its reliance on inferring intentionality and anticipating the future actions of the other party, thereby indicating the emergence of a security dilemma among states. The concept of the security dilemma was initially introduced by John Herz in 1950 and subsequently expanded upon by scholars Robert Jervis and Charles Glaser. It revolves around the notion that a state’s efforts to safeguard its own security can inadvertently lead to the insecurity of other states. Consequently, other entities react to safeguard their own security, thereby increasing the likelihood of conflict, which was not the primary intention of either state.

The security dilemma finds ample resonance within the framework of China’s endeavor to acquire ports as a means of strengthening the operational capabilities of the PLAN vis-à-vis a perceived adversary that has undertaken similar actions. The crux of the dilemma involves states functioning with limited information, perpetually speculating about the actions, timing, and locations of one another. The US and India, both countries with a significant stake in safeguarding their security, are likely to exacerbate the predicament by taking actions driven by the imperative to enhance their security or align themselves with a particular faction. This situation is further compounded by the presence of other nations experiencing military expansion in their vicinity.

China’s procurement of ports and subsequent endeavors to bolster its military capabilities bear resemblance to those of the US, leading to the establishment of 21 strategically located naval bases of considerable importance across the globe. From the perspective of China, it can be argued that at least six naval installations present a direct threat to China and its national security. Singapore is home to the Commander Logistics Group Western Pacific. Located in Buson, South Korea, the Fleet Activities Chinhae Naval Base is a prominent establishment. US Fleet Activity: Yokosuka and Sasebo, Japan, are also notable naval bases in the region, along with Naval Base White Beach, located in Okinawa, Japan, while USO Naval Base Guam serves as the headquarters for the Naval Expeditionary Force Command Pacific (NEFCPAC).

The establishment of naval bases by China has potentially engendered a sense of insecurity, as it appears to be a response aimed at mitigating a perceived threat and countering the dominant power of the US. The issue of counter-hegemony, in relation to China’s maritime ports and the security dilemma, becomes crucial in understanding this dynamic.

*This article was originally published on August 16, 2023.

Dr. Scott N. Romaniuk is an International Newton Fellow at the University of South Wales’ Faculty of Life Sciences and Education, the United Kingdom, and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Taiwan Centre for Security Studies (TCSS), ROC.

Professor Amparo H. Pamela Fabe is a visiting fellow of the International Centre of Security and Policing at the University of South Wales. She is an anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing expert and the Philippine National Police Representative to the ASEAN Senior Officials’ Meeting on Transnational Crime (SOMTC) and Women, Peace, and Security. She teaches at the Philippine Public Safety College. She is the 2023 Irregular Warfare Initiative Fellow, a joint project of the Modern Warfare Institute of the US Military Academy at West Point and Princeton University’s Empirical Studies of Conflict Institute.

Professor Christian Kaunert is Professor of International Security at Dublin City University, Ireland. He is also Professor of Policing and Security, as well as Director of the International Centre for Policing and Security at the University of South Wales. In addition, he is Jean Monnet Chair, Director of the Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence and Director of the Jean Monnet Network on EU Counter-Terrorism (www.eucter.net). Previously, he served as an Academic Director and Professor at the Institute for European Studies, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, a Professor of International Politics, Head of Discipline in Politics, and the Director of the European Institute for Security and Justice, a Jean Monnet Centre for Excellence, at the University of Dundee.