Analysis

There’s growing concern in defense and intelligence circles that the global recession has the potential to threaten America’s national interests. But a small group of academics and Pentagon policy-makers believe that the U.S. could benefit from the financial havoc.

With economies around the world on edge, they argue, a weakened-but-still-gargantuan USA has new opportunities to pressure adversaries through the strategic application of market trades and bank transfers. They call their theory “financial warfare.”

“Countries are under stress. Their populations are getting more and more agitated. So they’re more dependent on our investments,” one Pentagon official tells Danger Room. “This kind of financial warfare — it could be another tool in the toolkit.”

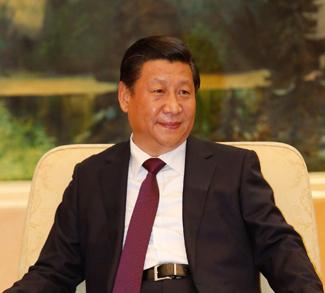

But financial warfare comes with all sorts of risks. The Unites States is deeply in debt to other countries — especially China, which holds over a trillion dollars in U.S. securities — and that kind of leverage, in the wrong hands, could be destabilizing. China’s prime minister said Friday he’s “a little worried” those investments may not be totally sound.

“You can envision scenarios where (creditor nations) launch a financial attack, you know — a Pearl Harbor on the dollar, if you will,” finance expert and Director of National Intelligence adviser James Rickards tells NPR. “And those are the things that I think national security professionals rightly think about. But it doesn’t even have to be that. It could just be China acting in its own best interests, in a way that causes interest rates to go up, the dollar to go down.”

Financial warfare has a past. During the 1956 Suez Canal crisis, for instance, President Dwight Eisenhower used market pressures to keep the UK and France from attacking Egypt by ordering the Treasury Department to flood the market with the Sterling. “This depressed the value of the British pound, causing a shortage of reserves needed to pay for imports,” writes Yale management professor Paul Bracken. “The message quickly got through to London, which, along with Paris, soon pulled out of the Canal.”

But that’s one of the few times America has openly used such a tactic, he adds. Instead, the U.S. has used blanket economic sanctions to punish foreign states, or frozen the bank accounts of terror groups and drug gangs. “But those are blunt instruments,” Bracken tells Danger Room. “Look at the embargo on Iraq in the 90s; the main effect was killing children and old people.”

Instead, Bracken suggests, the U.S. might consider targeting the “foreign bank accounts of the top 500 people” in an enemy state. “That financially decapitates a country’s elite.”

Last summer, former Justice Department official David Rivkin suggested punishing Moscow for its invasion of Georgia by going after the assets of the “ex-KGB siloviks and wealthy Kremlin-friendly tycoons” that “bankrolled [Russian overlord Vladimir] Putin’s rise” and really run modern Moscow. Around the same time, the National Security Council debated doing just that, but eventually demurred.

Other experts are advocating an approach that would seem to be diametrically opposed to financial warfare tactics. Rather than try to lean on countries through the markets, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s David Rothkopf says the U.S. should be heading up an effort to restore the global web of institutions that held the world economy together for so long.

Rothkopf told the House Armed Service Committee last week: “Unless the U.S. leads this process, spends the necessary capital to ensure the relevance of global financial institutions, invests the necessary political capital to create organizations that can truly manage global challenges, others will not follow and we will all suffer the dire effects of the ensuing institutional void.”