The post South China Sea Dispute: China’s ‘Gray Zone’ Is Shrinking appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>- The Marcos administration in the Philippines is internationalizing the South China Sea conflict, scrapping the bilateral approach of the Duterte years.

- US President Biden has reiterated that the US-Philippines mutual defense treaty applies to the South China Sea.

- ‘Gray zone tactics’ that may have worked previously are now more likely to elicit a response from Washington and other littoral claimants.

The United States and Philippines are planning their first-ever military training exercises outside of Philippines’ waters. The exercises are the latest in a series of moves suggesting a more active US stance on defending its allies’ sovereignty in the South China Sea. The overall objective is clear: remove the diplomatic and military ambiguity that China’s gray zone tactics thrive in.

Background

The South China Sea is a critical theater for Beijing, holding out the possibility of material wealth in its underseas mineral deposits and greater military security by pushing out the PLA’s defense perimeter from China proper. But Beijing’s sweeping claims to the waters overlap with other littoral states, namely Vietnam, the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia, and Taiwan. The resulting clashes have played out for decades, sometimes producing a sudden redrawing of the map, as was the case after China’s occupation of the Paracel Islands in 1974, and other times leading to a more gradual ‘slicing of the salami’ where a previous status quo slowly gives way to a new one, often by way of gray zone tactics designed to fall short of producing a direct military response.

The post South China Sea Dispute: China’s ‘Gray Zone’ Is Shrinking appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Global Wheat Markets Stabilize amid Ukraine War appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

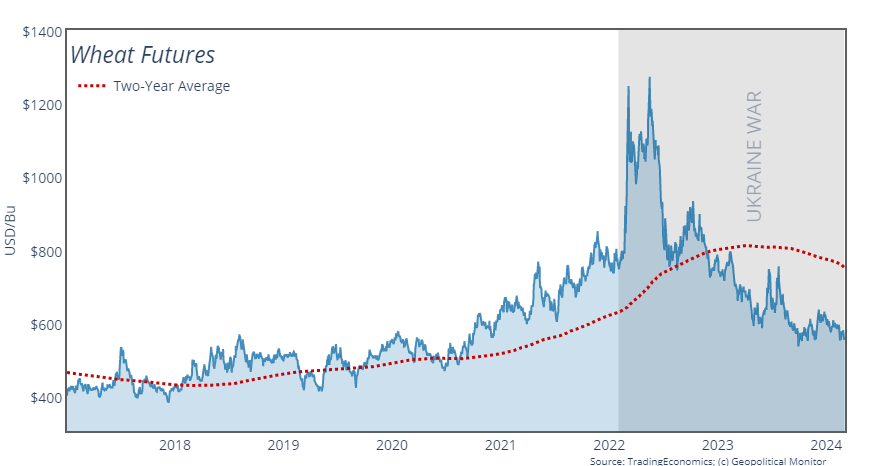

The geopolitical significance of staple foods like wheat is difficult to overstate, as price fluctuations over the course of human history have fueled the rise and fall of regimes, political systems, and even civilizations. At the dawn of 2024, global wheat markets are still recovering from significant supply-side disruptions from the pandemic and Ukraine war. This recovery is anything but assured looking ahead, as a complex interplay of factors threaten future price volatility. These include geopolitical tensions, supply and demand dynamics, weather conditions, and macroeconomic forces.

The post Global Wheat Markets Stabilize amid Ukraine War appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post ECB Makes Its Choice: Price Stability over Growth appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The lack of a cut comes as no surprise to the majority of investors, as inflation reductions across the continent have yet to calm the ever-inflation-averse officials of Germany and other major European economies, let alone their publics. Though the above graph highlights how inflation has dipped dramatically since its post-COVID highs, price levels have yet to settle into the sub-2% comfort zone in France, Germany, or Spain.

The post ECB Makes Its Choice: Price Stability over Growth appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Backgrounder: China Economy Year in Review appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

The year 2023 will go down in history as one of defied expectations for China’s policymaking establishment and the manifold analysts who called it wrong. Both were banking on a post-pandemic economic recovery that has yet to materialize, and this failure to launch is now shaping markedly gloomier forecasts for the year ahead.

One event framed the political context of the first half of 2023 more than any other: the abrupt end of China’s zero-COVID policy. The first few months of the year saw hospitals and health services overwhelmed with the sick, and a population fearful of catching a virus that had been aggressively stigmatized by the state. COVID-related deaths rapidly mounted, though no one can be sure of the exact number given underreporting in the official data. Estimates of total deaths range from the hundreds of thousands to millions.

There was a widely held expectation that, once this transitory period of epidemiological bloodletting was over, the Chinese economy would experience a boom much like the United States did after 2021, fueled by pent-up consumer demand and savings over the course of the pandemic. But this has yet to materialize, and the listless post-COVID recovery has thrown long-term economic contradictions into sharper relief, namely weak consumer spending, declining real estate markets, mounting debt burdens, and capital imbalances. Such was the story of 2023, and absent a fundamental restructuring of the Chinese economy to address these contradictions, there’s little reason to believe that 2024 will be materially different.

Consumer Spending

The creation of a confident and wealthy middle class, one that can power GDP growth through their consumption, has long been the white whale of Beijing’s economic planning. Numerous pivots have been mapped out over the years aimed at precipitating a shift from state-led investment (largely in the form of fixed capital formation) to consumption-led growth; none have met with success, and the exit from zero-COVID was no different.

It should quickly be noted here that quantifying consumer spending or any other economic metric in China is not a straightforward exercise. This is due in large part to the very real possibility of inaccurate or incomplete reporting from official organs ever sensitive to the political implications of negative data. Taking this well-established lack of transparency as a given, economic reality is most likely revealed by examining multiple data sources and placing the official numbers in their proper context.

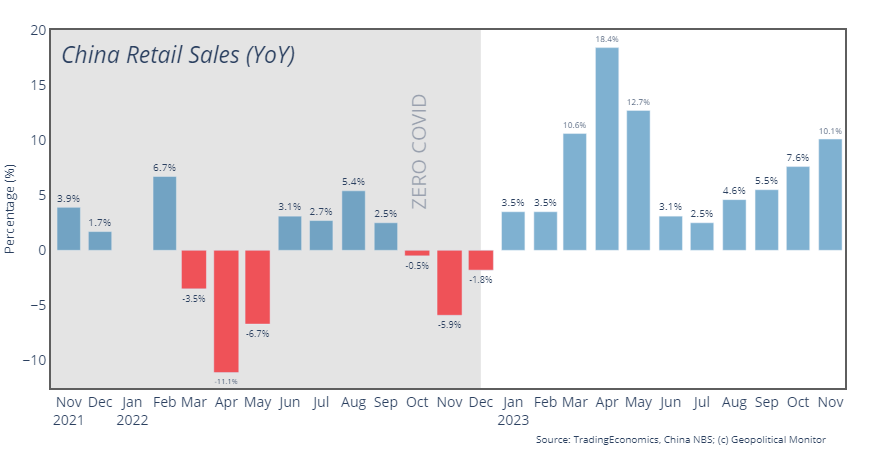

So far as the official data is concerned, consumer spending remained weak over most of 2023 before picking up in October (7.6% growth year-on-year) and November (10.1%); however, these year-on-year numbers are heavily skewed by the zero-COVID baseline of 2022. Conversely, consumer confidence surveys from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reflect consistent pessimism over the final few months of the year.

Weak consumer spending is also reflected in the stock market performance of two of China’s online retail giants. The stock for JD.com (HKSE) – a Chinese e-commerce company – shed nearly 60% of its value over the course of 2023. Alibaba stock (HKSE) similarly dropped by approximately 30% over the same period.

Golden Week – an extended holiday that typically represents the peak of annual travel and consumer spending – also disappointed, albeit with some positive indicators in certain sectors. In terms of travel, cross-border flights hit 1.477 million, approximately 85% of their pre-pandemic levels, but the number fell short of the 1.58 million government target. Singles Day – a one-day shopping event often likened to Black Friday – also disappointed in November, as indicated by the refusal of both Alibaba and JD.com to release their official sales numbers. This is a far cry from the pre-pandemic days when Singles Day sales data was proudly held up as proof of the implacable rise of e-commerce and the wider Chinese economy. Furthermore, third-party assessments of Singles Day have been dismal; for example, data provider Syntun estimated sales volume at 2.9% lower than in 2022, when economic activity was being throttled by zero-COVID policies.

The failure of these high-profile retail events speaks to the tenuous position of Chinese consumers, many of whom are being pressured on multiple fronts by COVID-era disruptions to their livelihood, eroding household wealth stemming from real estate, and a weak job market, particularly for young people. But there’s another dynamic at work here: the once-dramatic discounts of Singles Day are no longer remarkable because retailers have been slashing prices year-round to entice consumer spending. The trend is also evident at the macroeconomic level as rising deflation over several months of 2023, beginning in July. Price declines then accelerated in November, which posted an annualized drop of 0.5%, more than the 0.2% drop recorded in October and suggestive of a trend heading into 2024. The mere hint of an entrenched deflationary spiral is enough to freeze the blood of policymakers as it harkens back to Japan’s post-1990s lost decade, which combined a sudden collapse in property values with long-term deflation, creating a cycle of stagnation that still reverberates to this day.

Real Estate

An overstretched consumer class is understandable in the context of China’s ongoing property crisis, which erupted during the early phases of the pandemic. The crisis originally centered on Evergrande, the second-largest property developer in China, which since 2021 has been struggling to maintain solvency after having defaulted on billions worth of loans. The ensuing vortex of collapsing confidence in real estate markets then enveloped Country Garden, mainland China’s largest private property developer, which warned in October that it is at risk of defaulting on its over $200 billion worth of debt obligations. Reuters has since reported that state authorities entered into talks in November with Ping An, a private insurance giant, urging it to take a controlling stake in Country Garden so as to alleviate some of the real estate developer’s cash flow concerns.

On a systemic level, the risk is clear: with every new default, the peril ratchets up for the remaining developers who must grapple with declining confidence. The dynamic is compounded by the nature of the Chinese real estate market, where buyers often secure their home by placing large deposits before construction has started (a system often compared to a Ponzi scheme). Such practice is the norm rather than the exception, with as much as 90% of new homes being purchased pre- or during construction. A Nomura Group report estimated some 20 million units (the equivalent of 20 times Country Garden’s output) of unconstructed and delayed pre-sold homes across the country at the 2023. The report also warns of mounting social instability in 2024 as the number of undelivered units from distressed developers ticks upward, barring more direct government intervention.

The extent of the debt levels of these distressed developers is significant. Taken together – and not including the numerous smaller developers struggling to remain solvent – Evergrande and Country Garden’s combined liability burden comes in at around $550 billion, equivalent to approximately 3% of China’s total GDP. Such sizable liabilities represent a contagion risk for China’s banking system, reflected in the recent bankruptcy of the Zhongzhi Enterprise Group, whose Zhongrong trust banking arm first signaled solvency issues in August of 2023. Both lenders were highly exposed to real estate investments, and the eventual bankruptcy came despite active efforts by the authorities to stabilize their finances.

On the ground level, Chinese households are seeing their wealth eroded by diminished sales and demand, and the effects are not evenly distributed. Real estate markets in tier 1 cities like Beijing and Shanghai, and to a lesser degree tier 2 cities like Guangdong and Jiangsu, have remained resilient relative to tier 3 and 4 cities. Similarly, new builds have historically tended to outperform existing homes due to consumer preference.

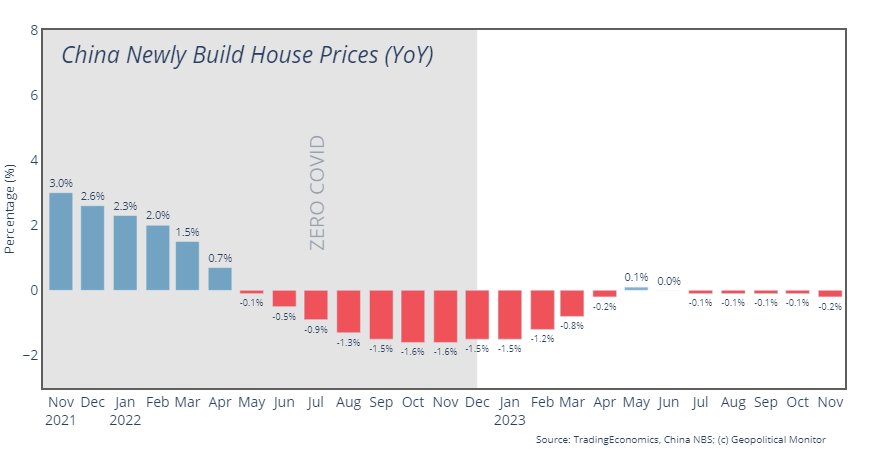

Country-wide, new house prices dropped by approximately 4.5% over the course of 2023 according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) data, with price declines accelerating over the last two months of the year, posting 0.2% and 0.3% month-on-month drops respectively. Third-party assessments of the existing home market have also skewed negative. The Tianjin-based Beike Research Institute estimated a near 18% drop in prices since August 2021.

It should be noted that the NBS data likely does not reflect a complete picture of China’s real estate markets, as it is based on a survey sample using ambiguous methodology as opposed to aggregates. Moreover, the lack of public disclosure of final sales price makes any reliable third-party verification of the official numbers impossible.

The authorities have not taken this slowdown in a sector representing as much as 30% of China’s GDP lying down, and steps have been taken at all levels of government to stimulate demand and restore buyer confidence. These include a reduction in minimum down payments, waiving restrictions on multiple home purchases, and loosening financing restrictions. In large part, the story of China’s economic health in the year ahead boils down to whether or not these stimulus measures achieve their objective of stabilizing property prices and by extension the fiscal health of China’s giant developers and the banking system that sustains them. However, market watchers are remain unconvinced, with most economists polled by Reuters predicting a tepid 1% price growth rate overall in 2024. Their lingering pessimism stems from the structural nature of the problem at hand: after decades of speculative building, cities are severely over-supplied just as home demand is peaking due to economic and, even more alarming due to the long-term implications, demographic pressures. The problem is particularly acute in tier 3 cities, which together account for around 60% of China’s GDP. As recent as 2021, some 78% of total housing construction was concentrated in such cities.

Foreign Investment

‘Decoupling’ and ‘friend-shoring’ emerged as popular buzzwords in the wake of President Trump launching his trade war with China; however, the immediate impact of the policy with regard to FDI flows remained muted initially. According to research from the Rhodium Group, this temporary grace period resulted from a combination of macroeconomic factors, capital control circumvention, and overly optimistic reporting by the state authorities. In actual fact, capital inflows for long-term ‘greenfield’ projects have been declining since 2020, though the negative effects have been mitigated somewhat by strong demand among multinationals to establish China-based production targeted at the Chinese market. The end result, according to Rhodium, is an FDI outlook that is ‘lower for longer,’ thus reducing the likelihood of foreign investment rescuing GDP growth from the abovementioned contradictions in China’s domestic economy.

The more recent data is much more supportive of the idea that US-China geopolitical and trade tensions are reverberating in China’s inward FDI flows. The data point that immediately jumps out is the third quarter 2023 net deficit of $11.8 billion in FDI flows – the first such deficit since data collection began in 1998.

On one hand, it should be noted that monetary policy was a significant tailwind for multinationals looking to repatriate profits from China for safer returns in the United States. Yet it’s also true that a rare, bipartisan consensus appears to be coalescing in Washington, one that views China as a peer-level rival and antagonist despite recent attempts by the Chinese leadership to pivot back to the pre-Trump status quo. The Biden administration’s outbound investment screening program is emblematic of the new reality. The program will grant the Treasury Department authority to monitor and potentially prohibit investments involving sensitive technology in countries of concern, notably China and the Hong Kong SAR. Moreover, it’s not only the United States looking to restrict and regulate its outward investments to China. The European Union also plans to table an initiative in 2024 that will restrict investment in certain sensitive technologies on national security grounds. A successful push into investment and export controls by Brussels would mark a paradigm shift in the bloc’s security calculations, as the issue has long been a source of friction between national and EU-level governments.

While the devil will be in the details regarding how restrictive these outward screening regimes ultimately are, the new controls clearly do not bode well for investor confidence in China, especially because, like with sanctions, there is a tendency toward over-compliance where companies err on the side of caution to avoid punishment.

Government Debt

Debt remains a pressing issue for the Chinese government, though disagreements exist over severity. What’s unequivocal is that the broad long-term trend has been one of accumulation, with China’s total debt increasing four-fold, from 70% of GDP in the mid-1980s to 272% of GDP in 2022. And where the post-COVID global tendency has been deleveraging, China has moved in the opposite direction; for example, emerging markets excluding China shed 7.6% in debt-to-GDP in 2022 where China’s debt increased by 7.3%. Going back further, China accounts for over half of the entire world’s total debt-to-GDP increases since 2008.

The breakdown of China’s debt obligations is also a matter of debate owing to the opaque and often political nature of the state’s fiscal responsibilities. These can range from the straightforward local governments, which act as primary service providers despite being severely limited in their toolbox of revenue-raising instruments, to unprofitable state-owned enterprises that buttress social stability via mass employment or provision of critical services, to the countries and lending entities underpinning high-level foreign policy initiatives like Belt and Road. In nearly all cases, all roads lead back to China’s banking system, which, absent government intervention would be saddled with non-performing debts, creating systemic risk.

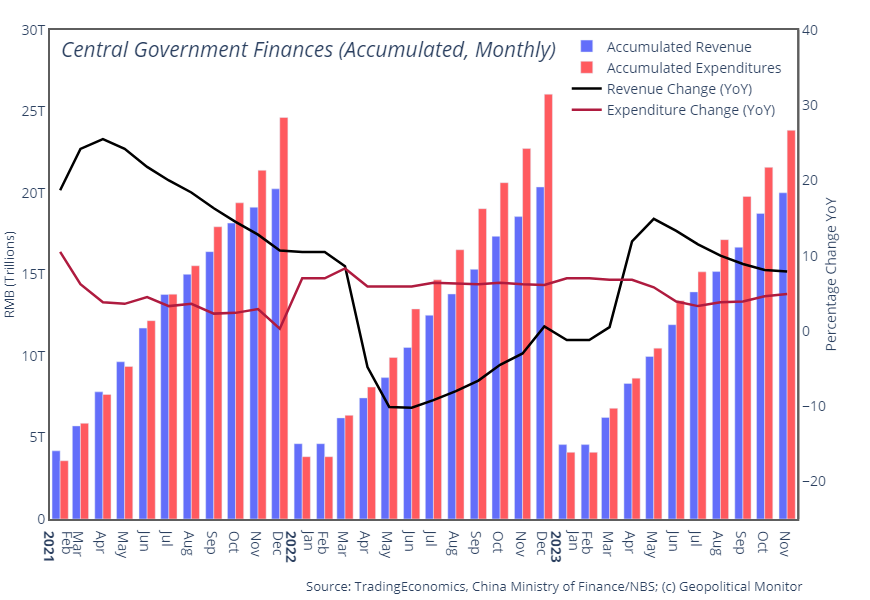

It was the combination of these overt and implicit responsibilities that prompted Moody’s to lower its outlook on China’s A1 debt rating from ‘stable’ to ‘negative’ in the beginning of December, a move that prompted a strong rebuke from the state media. The ratings house cited a likely bailout of local and regional governments, which themselves will be fiscally stressed by declining property values, as reasons for the downgrade.

An interesting perspective comes from Michael Pettis of Peking University, who points out that much of the focus on China’s debt burden hones in on the extent of the government’s liabilities. However, the real structural contradiction lies on the other side of the ledger – assets – where years of misallocated, state-led investment has engendered inflated valuations of what are actually non-performing capital expenditures. These valuations can be sustained only so long as the credit is available to refinance them, and the inevitable credit crunch will unleash a systemic reckoning where imaginary valuations are reconciled with reality. In light of Reuters reporting in October that the authorities are ordering state-owned banks to roll over local government debts at longer terms with lower interest rates, it would appear the reckoning is being pushed into the future. But the money to pay down these liabilities will have to come from somewhere, and until that happens the debts will continue to corrode the balance sheets of China’s major banks, hampering overall liquidity whether or not they carry the de facto ‘non-performing’ label. Incidentally, these refinancing deals are also cited by in the Moody’s downgrade as examples of the costs of local government debt being borne by the broader public sector.

Looking Ahead to 2024

Short-term success will not be measured in growth rates of 5, 6, 7% – those days are over, at least for the time being. Rather, it will come in the form of a controlled and orderly disentangling of the structural contradictions at the heart of China’s economy. Failure on the other hand could resemble the ‘lost decade’ suffered by Japan, a country that also struggled to reconcile high debt loads with low growth amid a cascading real estate collapse. But Beijing does have some advantages available to it that Japan did not in the 1990s, not least of which is the historical perspective gained from Tokyo’s long period of economic turmoil.

We can expect the recent barrage of regulatory easing and olive branches extended toward the private sector to continue in 2024, all with an overriding goal of restoring market confidence. Already the ascendance of pro-private sector and pro-growth jargon is evident in state communications, which had only recently been dominated by national security concerns. But China’s debt burden will impose hard limits to what the state authorities are able to accomplish in terms of bailing out distressed entities, whether local government, bank, or property developer. Returning to the tried-and-tested approach of mass supply-side stimulus is also presumably off the table barring a crisis, and even then it would merely be putting off the inevitable economic pain. Whatever the actual GDP growth rate was for 2023 – the Rhodium Group pegs it at around 1.5% – the year ahead will likely be modestly higher, but still well short of the official target of 5%.

The post Backgrounder: China Economy Year in Review appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Backgrounder: The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>China’s People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) evolved out of a military predicament specific to the post-civil war period: How does a government without a formal navy protect its coastline from attack? Fast-forward to the present, and the PAFMM is still being charged with unconventional tasks, though the question has now evolved into: How does a government exert control over a contested body of water without triggering a ‘hot’ war with rival claimants?

This backgrounder explores the history, composition, and tactics of the ‘little blue men’ of China’s littoral waters – the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia.

Background

What is the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia?

The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) is a pseudo, civilian-military coast guard that engages in ‘gray zone’ operations intended to establish de facto control over disputed waters near China. These operations include providing armed escort for Chinese fishing vessels, intimidating commercial vessels from other nations in disputed waters, and dissuading the coast guards and navies of other claimants from policing their own waters for fear of potential escalation with Beijing.

PAFMM operations are low-intensity and designed to generate acquiescence on the part of rival claimants; in essence, they seek to win the war without a shot being fired. These tactics might involve aggressive forays into waters policed by rival claimants, or more passive ‘rights protection’ missions in waters already firmly within China’s control under the unspoken credo that maritime jurisdiction is merely presence.

For evidence of the success of PAFMM operations overall, one must look no further than the evolving map of the South China Sea.

In keeping with its history as a ‘people’s militia,’ the PAFMM is composed of a mix of maritime workers, who receive military training similar to reserves or national guard and are subsequently eligible to be ‘called up,’ and conventional full-time military recruits. This atypical force composition follows a much more conventional line of command that reaches all the way up to Beijing. Consequently, the US military now views the PAFMM as a branch of the PRC armed forces on the same level as the PLA Navy and China Coast Guard.

Determining the exact size of the PAFMM remains a difficult task due to its vague and shifting membership – fishermen can be ‘drafted’ in and out of the force as the situation demands. Specific details about the militia also rarely make it into official government documents (in fact, the ‘People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia’ itself is a moniker bestowed by the US Department of Defense). One estimate from US Naval War College expert Andrew S. Erickson puts the number of large vessels at 84. Others have estimated that the PAFMM can leverage as many as three thousand small vessels at any given time. And these numbers can be considered conservative when put in historical context: according to one 1978 estimate, the PAFMM was once composed of 750,000 personnel and 140,000 vessels.

History of the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia

The PAFMM’s history stretches back nearly as long as the PRC itself. Comprising mostly of untrained fishermen, the militia was created soon after the civil war. Like the PRC’s ground-based armed forces, the PAFMM followed the Maoist logic of ‘people’s war’; it also intended to solve the more practical problem of shortfalls in naval assets and expertise among the early CCP leadership. The immediate task of the early PAFMM was to defend the mainland from Nationalist incursions. The militia was also employed in attempts to retake coastal islands from the KMT during the 1950s (the first and second Taiwan Strait crises).

But these early forays were just the beginning of the PAFMM’s enduring role in China’s littoral waters. Since its inception, the militia has been a central player in numerous geopolitical stand-offs. In some of these events, the presence of the PAFMM was arguably more decisive than that of the conventional (and historically underfunded) People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). They include:

- Capture of the Paracel Islands from Vietnam in 1974, when the presence of PAFMM vessels – many of them carrying armed crew – helped slow down the South Vietnam government’s decision-making and ultimately deter an armed response. The South China Sea island chain remains under PRC control.

- USNS Impeccable incident in 2009, when PAFMM and PLAN ships swarmed an unarmed US Navy ocean surveillance vessel after it encroached on China’s 200-mile EEZ south of Hainan. The confrontation involved two China-flagged fishing vessels attempting to run over the Impeccable’s sonar equipment and then blocking its path of escape.

- Harassment of Vietnamese survey vessel in 2011, when a Vietnamese seismic survey ship (Binh Minh 02) had its cables cut by Chinese vessels. The incident was notable in its proximity to Vietnam’s coast, taking place just 43 miles southeast of Con Co Island.

- Scarborough Shoal clash in 2012, when the Philippine Navy attempted to board and arrest Chinese fishermen suspected of illegal fishing around Scarborough Shoal, triggering a standoff between Philippine and PLA Navy vessels where Beijing came away the victor. The initial fishing vessels were reportedly PAFMM members who helped coordinate the subsequent coast guard and naval response. Scarborough Shoal remains under PRC control.

- Haiyang Shiyou-981 rig incident in 2014, when Vietnamese vessels attempted to preempt the establishment of a Chinese oil platform near the disputed Paracel Islands. PAFMM involvement came in the form of the 35-40 fishing vessels that helped cordon off the oil platform and prevent it from being harassed by Vietnamese vessels. These PAFMM ships also reportedly harassed Vietnamese fishing vessels operating on the outskirts of the cordon.

- Senkaku Islands surge in 2016, when up to 400 fishing boats entered Japan’s territorial waters around the disputed Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu in Chinese), complete with an escort from China Coast Guard vessels. The incident mirrors a similar surge in 1978, when hundreds of Chinese fishing vessels swarmed the islands ahead of negotiations for a bilateral peace treaty.

- Whitsun Reef surge in 2021, when over 200 fishing vessels were spotted moored off of a boomerang-shaped reef claimed by both the Philippines and China. The presence of the ships drew official complaints from Manila, and the presence of PAFMM vessels subsequently declined.

PAFMM: A Novel Geopolitical Tool

In light of the above, the PAFMM’s utility for China’s government becomes clear. For one, the force’s deniability – whether or not PAFMM ships are a deployed military or ‘patriotic fishermen’ – makes it perfect for the type of gray zone operations that have helped China rapidly (and likely permanently) alter the geopolitical map of the South China Sea. The goal has always been to advance China’s territorial interests without eliciting a direct military confrontation, either from rival claimants or their allies. Just consider how, over the past two decades, China has been able to occupy various features lying within the de jure EEZ of a US treaty ally in the Philippines, and all without a kinetic response from Washington.

Second, the PAFMM helps realize the critical aspect of maritime sovereignty: ground-level presence. Over the past two decades, China’s sweeping claims have been subjected to all manner of legal and academic challenges, ranging from disputes over the historical evidence to a contrary judgement on the entirety of the nine-dash line claim from the Hague’s Permanent Court of Arbitration. Yet this same period has seen China establish a permanent and highly militarized footprint throughout the South China Sea. Why? Because the PAFMM has helped establish an enduring presence in the area, and presence is often the foundation of a credible sovereignty claim (legally dubious or otherwise). Fishers in other littoral states are also patriotic, and many are angry after seeing their catches dwindle. However, their governments lack the ability to organize, train, supply, pay, and ultimately leverage them as a geopolitical tool in order to stake a claim at a given reef. Moreover, they lack the backing of China’s increasingly powerful Coast Guard and PLAN vessels, which so often are also present and serve as a suggestive back-up to the PAFMM’s more aggressive maneuvers.

The post Backgrounder: The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Backgrounder: Myanmar’s Kyaukpyu Port appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

Summary

Kyaukpyu is a small fishing village of some 50,000 people located in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. This sleepy hamlet is where China wants to establish the next maritime hub of the Belt and Road Initiative. The plan is to construct a world-class deep-water port and free trade zone, thus allowing China’s Yunnan-based industries to gain easier access to global markets via the Bay of Bengal.

However, like some other Belt and Road projects, political concerns are muddying the waters. Kyaukpyu Port ranks highly on a long list of controversial Chinese development projects in Myanmar, a list that includes the cancelled Myitsone hydropower dam and the ever-contentious Letpadaung copper mine. The port’s detractors worry that it will force Myanmar into a subservient position of debt servitude for decades to come. Supporters argue that these concerns are eclipsed by the economic gains to be had from building a bustling new port complex on what is otherwise a largely underdeveloped swathe of Myanmar’s coast.

This backgrounder will explore the economic promise and geopolitical ramifications of the Kyaukpyu Port.

Background

Kyaukpyu Port is similar to Belt and Road projects elsewhere, notably Gwadar Port in Pakistan and Hambantota in Sri Lanka, the latter of which passed into China’s possession on a 99-year lease after the Sri Lankan government found itself mired in fiscal crisis (in part due to the loans needed to build the port in the first place).

Yet in the case of Kyaukpyu Port, it’s worth noting that Myanmar has had a strong historic aversion to being drawn too closely into China’s economic orbit, which has resulted in an arms-length approach to various Belt and Road projects. This aversion was evident in the popular outcry that led to the (perhaps temporary) demise of another Belt and Road project: the $3.9 billion Myitsone dam, which intended to build a series of hydropower stations on the headwaters of the Irrawaddy River. The dam was nearly universally opposed by the Myanmar public due to its social and environmental costs (over 15,000 people would need to be relocated), and the terms of the original deal, which were viewed as excessively favorable for China (the project would see 90% of its electricity exported to China’s Yunnan province).

Put simply, Naypyidaw’s baseline attitude toward Beijing is one of skepticism. But in Myanmar as in other locations along the BRI’s economic corridors, there aren’t many alternative investors willing to step in and supplant Beijing’s willingness and ability to fund major infrastructure initiatives. With the advent of the post-2010 reform process, Myanmar opened up its domestic political process, secured sanction relief, and attracted new sources of investment – all of which served to lessen the country’s reliance on China. However, this rapprochement suffered a breach amid the Rohingya crisis of 2017, followed by open rupture after the 2021 coup effectively ended the country’s pseudo-democratic experiment. Now, Myanmar once again finds itself isolated and reliant on Chinese finance and support, and this reliance is reflecting in the terms of the Kyaukpyu Port and other BRI projects.

Kyaukpyu Port

Though the Kyaukpyu Port was first proposed all the way back in 2007, the project has struggled to get off the ground ever since. This is only partially due to the aforementioned skepticism on the part of the Myanmar authorities. Another drag on the project is the unclear economic logic underpinning it. Pre-coup there were numerous competing facilities in the neighborhood, most notably the Japan-financed Thilawa Port just south of Yangon. Thilwa Port can handle vessels of up to 20 thousand DWT (tons deadweight) and 200 meters in length; it has benefitted from ‘spillover’ from the nearby Yangon Port, which is increasingly constrained by the trade boom of the past decade. Thilawa’s main external patron is Japan, which has poured hundreds of millions into expanding the port’s facilities, and those of a nearby industrial park. Post-coup trade volumes have dried up and major players like Adani Ports have been forced to divest or risk falling afoul of Western sanctions.

Due to the country’s pre-existing infrastructure networks, many of which link up with bustling metropolis of Yangon, critics assert that Kyaukpyu would be less about developing the Myanmar economy in a holistic sense and more about creating a new and mostly China-owned economic conduit linking Yunnan province with the Indian Ocean.

In other words, the overriding logic of the project has always been geopolitical rather than economic.

Negotiations over Kyaukpyu Port have been ongoing since 2015, when the project was originally awarded to China’s CITIC Group, one of the country’s first state-owned investment consortiums. The original terms of the deal were controversial to say the least, particularly the $7.3 billion price tag that was initially floated. By way of contrast, the first phase of the Hambantota Port project cost just $361 million back in 2008, and Gwadar Port cost about $248 million to build back in 2003.

How that $7.3 billion would have been spent will remain a mystery. For its part, according to the CITIC, the port would have an annual capacity of 4.9 million containers, which is around the size of the Hanshin ports servicing the Osaka-Kobe region of Japan. Another mystery is the fiscal gymnastics that would have allowed a country with a GDP of just $71 billion (about the same size as Luxembourg) to pay the money back without triggering fiscal meltdown. The deal’s original supporters within the Myanmar government maintained that the sum would be repayable, and that the project would proceed on a phase-by-phase basis, with a certain threshold of success having to be reached before the next phase could proceed.

Another point of contention was the ownership stake in the port. CITIC originally sought a controlling stake of anywhere between 70-85% in the project.

The original terms of the deal were subsequently renegotiated by the Suu Kyi government following the 2015 election. As a result of these talks, the scope of the project was significantly downgraded, with the port to be just one seventh the size and capacity of the original plan. The fiscal burden was also reduced for Myanmar, which would have to borrow/pay around $1.3 billion in exchange for a 30% stake in the project, up from the original 15%.

Yet even with these more favorable terms, the project remained bogged down in a state of regulatory limbo in the lead-up to the 2021 coup, with the CITIC still submitting environmental and social impact studies in late 2019, only to have COVID-19 destroy any economic and political impetus for the project soon after. The dynamic has changed since the Military Council took over in 2021. Heavily sanctioned by the West and fighting a slow-burn civil war throughout the country, the Myanmar authorities have lost any leverage they previously had dealing with China. Beijing on the other hand is happy to engage with Naypyidaw and lessen its international isolation, though now it has a free hand to push for the resumption and expedition of the Kyaukpyu Port project – and this is precisely what China is doing.

A Belt and Road project with strategic significance

There’s a significant military dimension to Kyaukpyu, as the location is geopolitical significant and would grant China another outpost in its ‘string of pearls’ strategy meant to encircle India in the Indian Ocean. The site is almost directly across from INS Varsha, near India’s coastal city of Visakhapatnam. INS Varsha will be the future headquarters of India’s Eastern Naval Command. The scope of the Kyaukpyu project – speak nothing of the size of the required loans and their potential to ensnare Myanmar’s finances – implies that long-term military calculations are underpinning China’s enthusiasm for the project. However, the permanent stationing of PLA military assets in Myanmar remains highly unlikely given the country’s longstanding sovereignty sensitivities vis-à-vis Beijing.

Kyaukpyu Port could also help to lessen China’s dependence on seaborne energy imports. In fact, gas and oil pipelines have already been built to link Kunming and Kyaukpyu. Paradoxically, these pipelines actually served to further inflame local opposition against future stages of Kyaukpyu Port, as these early projects were characterized by poor compensation for land purchases, environmental shortcuts, and overreliance on foreign labor at the expense of local workers.

Of course, there’s an important economic dimension as well. Kyaukpyu would give Yunnan-based industry easier access to global markets via the Indian Ocean. But even more importantly, it would provide new political impetus for high-speed rail projects linking Ruili on the China-Myanmar border to Mandalay and eventually the coast. A contract was signed in 2011 to establish a Kunming-Rangoon rail corridor, but the project was cancelled in 2014 following widespread protests against the terms of the deal, which would have granted the railway to China as a 50-year concession. Road projects would also shadow the rail corridor between Ruili and the coast to improve transport capacities for goods moving from Yunnan to Kyaukpyu Port.

The post Backgrounder: Myanmar’s Kyaukpyu Port appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Second Thomas Shoal Emerges as South China Sea Flashpoint appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The overriding contradiction remains the same: Beijing’s ‘gray zone tactics’ altering the de facto map of the region by consolidating a presence in far-flung corners of the South China Sea, and always to the detriment of the territorial claims of other littoral states. Manila on the other hand has been pushing back against these actions with newfound zeal, as the current Marcos administration has been much more willing to press the issue and draw diplomatic and military assistance from its treaty ally in the United States than the previous Duterte government.

The character and extent of this US support will go far in determining how tensions surrounding the Second Thomas Shoal play out. And given the marked absence of diplomatic good faith, coupled with China’s slow-but-steady territorial advance of recent years, pressure is mounting on both Manila and Washington to collectively draw a line in the proverbial sand. It follows that we could be witnessing a geopolitical paradigm shift in-the-making, one where kinetic options begin to take precedence over diplomatic ones in the disputed waters of the South China Sea.

The post Second Thomas Shoal Emerges as South China Sea Flashpoint appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Belt and Road at 10: A Paradigm Shift in Development Finance? appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

Ever since its largely unremarkable inception in a speech at Kazakhstan’s Nazarbayev University in 2013, President Xi’s landmark Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has represented a moving target for analysts and policymakers. The branding has evolved – from a Maritime Silk Road of the 21st century, to One Belt One Road, before finally settling on the current form. So too has the project’s geographic scope, which branched out from its original Eurasian focus to eventually encompass Africa, Oceania, Latin America, and even the Arctic. And in a shift beyond the original economic thrust of promoting infrastructure development, Belt and Road has evolved into a banner under which numerous educational, environmental, and technological exchanges proliferate around the world. Just two of many examples include the ‘Digital Silk Road,’ which seeks to expand the footprint of China’s tech giants and afford them a larger role in shaping global standards, and the ‘Space Silk Road’ which facilitates satellite launches and technical cooperation among developing countries.

It’s not only the Belt and Road Initiative that has been changing over the past decade. Shifts in the global distribution of economic and diplomatic power have also unfolded, leading to a gradual eclipse of US preeminence that has favored the expansion of the BRI, a platform that is generally presented as an alternative to traditional Western circuits of development finance. A similarly upward trajectory can be discerned in two other young institutions synonymous with China’s expanding global clout – the BRICS grouping and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) – both of which have expanded their membership and diplomatic influence in recent years.

From the vantage point of 2023, the historical weight of Belt and Road is undeniable. Even those ascribing a more nefarious or ideological dimension to China’s motivations are inclined to admit that BRI has become emblematic of not just the Xi Jinping era of Chinese politics, but also a wider paradigm shift in how Beijing views its place in international society. But does the high visibility and global reach of Belt and Road mean that the project has achieved its original objectives? This question will be explored in greater depth in the sections below.

“Mobilize resources, leverage growth drivers, and connect markets”

Mobilizing Resources: China as a Developmental Finance Superpower

Belt and Road can be viewed as ‘globalization with Chinese characteristics’ and, like conventional globalization, it is a fundamentally economic phenomenon that over time inevitably creeps into the political and military spheres, ultimately generating ever-deeper integration and dependencies. The central pillar of BRI remains trade facilitation via the creation of hard infrastructure (ports, roads, rails) and reduction of cross-border trade barriers (customs, inspections, quarantine). And the overriding goal is to connect global markets to the economic hub of China, thus securing an unimpeded stream of primary inputs and a permanent consumer base for Chinese exports.

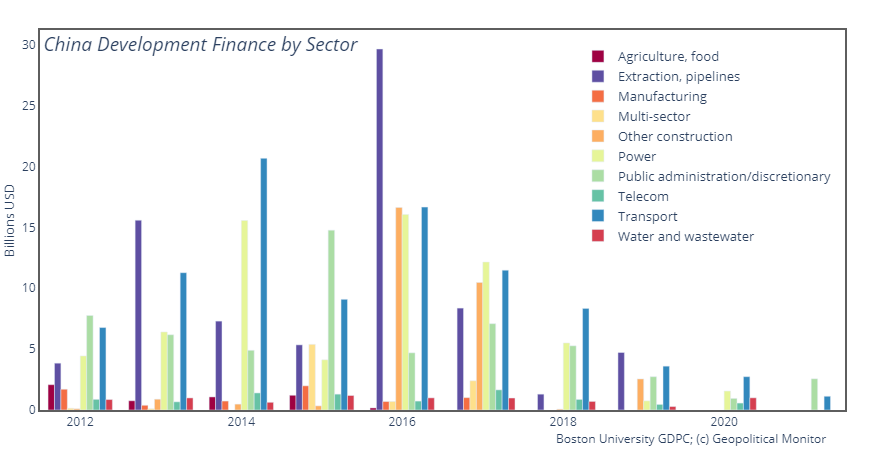

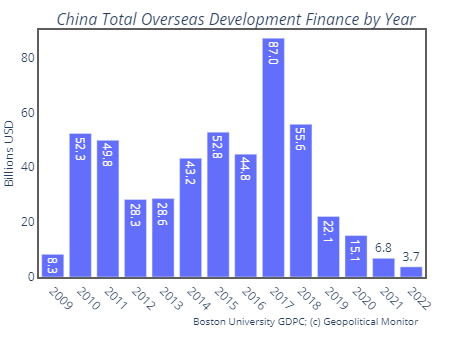

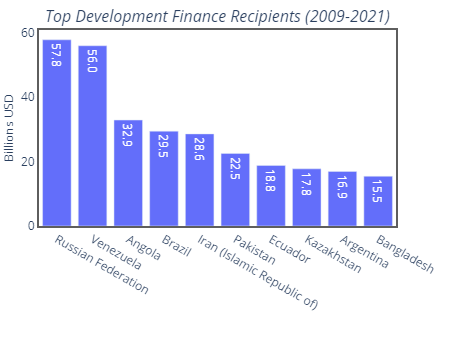

The endeavor has above all entailed massive outlays of infrastructure finance to the developing world. It’s generally believed that over $1 trillion has been spent so far, with estimates varying due in part to frequent confusion over whether a given project bears the official BRI branding. These expenditures have propelled China to the commanding heights of global development finance: the country now spends around $85 billion per year on foreign infrastructure development, outspending the United States and other major powers on a 2-to-1 basis or more.

China’s spending also differs qualitatively from other global lenders.  For one, it overwhelmingly favors loans over grants. In the BRI era, China has adopted a 31:1 ratio of loans to grants, and a 9:1 ratio of Other Official Flows (OOF) to Official Development Assistance (ODA). State-owned lenders have also extended loans with higher interest rates and shorter grace periods and maturation horizons than multilateral creditors on average. In an examination of 100 leaked BRI contracts – just a small sample of the tens of thousands of agreements that remain shielded from public scrutiny – Anna Gelpern et. al identify several distinctive characteristics of this surge in Chinese lending: 1) development loans are largely opaque and subject to extraordinarily strict confidentiality clauses; 2) loans tend to restrict the possibility of multilateral collective bargaining mechanisms such as the Paris Club process; and 3) loans often include various cancellation, linkage (to other China-linked loans), and repayment restrictions that together amount to extraordinary leverage on the part of the creditor, amplifying Beijing’s economic and political influence over borrowing parties.

For one, it overwhelmingly favors loans over grants. In the BRI era, China has adopted a 31:1 ratio of loans to grants, and a 9:1 ratio of Other Official Flows (OOF) to Official Development Assistance (ODA). State-owned lenders have also extended loans with higher interest rates and shorter grace periods and maturation horizons than multilateral creditors on average. In an examination of 100 leaked BRI contracts – just a small sample of the tens of thousands of agreements that remain shielded from public scrutiny – Anna Gelpern et. al identify several distinctive characteristics of this surge in Chinese lending: 1) development loans are largely opaque and subject to extraordinarily strict confidentiality clauses; 2) loans tend to restrict the possibility of multilateral collective bargaining mechanisms such as the Paris Club process; and 3) loans often include various cancellation, linkage (to other China-linked loans), and repayment restrictions that together amount to extraordinary leverage on the part of the creditor, amplifying Beijing’s economic and political influence over borrowing parties.

The limited public data on how these loans are collateralized points in different directions. Research from AidData found that 40 of the 50 largest loans from China state-linked creditors offered collateral in the event of default, and that 83% of loans to countries that fell in the bottom quartile of global fiduciary risk were collateralized. This would seem to suggest that collateralization is Beijing’s preferred risk-mitigation strategy. However, leaked contracts elsewhere hint at less severe risk mitigation measures. Upon examination of a leaked BRI contract for road construction in Kyrgyzstan, Michael Schroeder found no such collateralization clauses, though noted the possibility of political influence being exercised through the various atypical clauses outlined above. All in all, while collateralization appears to be a recurrent theme in high-risk projects, its overall prevalence cannot be determined so long as the vast majority of BRI agreements remain secret.

In closing it’s worth noting that BRI-related infrastructure finance has helped fill a market gap in the chronic shortage of infrastructure finance across the developing world, with annual investment requirements estimated at anywhere between $2.9-$6.3 trillion. Even taking the high outlays of BRI-related finance into account, infrastructure investment is still expected to fall short by around $360 billion annually through 2040. In many cases, Chinese finance is the only option available for governments seeking to build critical infrastructure, and this lack of competition helps explain the favorable terms that Chinese lenders have often managed to secure in BRI contracts.

Leveraging Growth Drivers: BRI as an Economic Engine

Another clause in the abovementioned Kyrgyzstan contract is noteworthy: “the goods, technologies and services purchased by using the proceeds of Facility shall be purchased from China preferentially, and the technical standards to be used shall follow relevant Chinese and international standards.” Here the borrowing party is legally obliged to purchase labor and inputs sourced from China, and to abide by Chinese standards to the ultimate detriment of any potential competitors in the global arena. Thus, it’s not only favorable financial terms where China’s core interests are advanced. It’s also the domestic economic tailwinds produced from Chinese labor, inputs, and expertise being exclusively used to build some of the largest infrastructure projects in the world.

In this sense, Belt and Road is an externalization of the supply-side economics that drove China’s breakneck economic development since the 1980s. State-directed infrastructure investment has played an outsize role in China’s modern development story, so much so that infrastructure stimulus remains a policy failsafe to be reverted to in times of economic trouble. Yet Beijing’s domestic infrastructure spending has proven so prolific that it is now producing diminishing returns. Anecdotes of ‘roads to nowhere’ and ‘ghost cities’ proliferate as all levels of government try to generate economic activity through state-led construction, leaving ballooning debt loads in their wake. Enter the Belt and Road Initiative, which represents a proverbial escape hatch from infrastructure oversaturation without having to forego the perks of China’s established economic model. Moreover, BRI allows the debt risks inherent to domestic infrastructure development to be circumvented by offloading them onto borrowing countries; though, as later sections will illustrate, these risks cannot be mitigated entirely.

The economic benefits of BRI are reflected in the annual statements of China’s largest state-owned construction companies. China Railway Group (CREC), a major player that helped build notable BRI links such as the China-Laos and Addis Adaba-Djibouti railways, saw its revenue nearly double from 558 billion yuan in 2013 to 1,073 billion in 2021. China Railway Construction Corp (CRCC), a rail giant with over 340,000 employees, saw its Fortune 500 ranking of global companies jump from 100 to 39 over the same span. Taken together, from 2014-21, Chinese iron and steel makers invested some $17.5 billion in BRI countries, up from $4.7 billion over the previous eight years. These surging investment flows, facilitated in large part by the state under the BRI banner, have helped Chinese SOEs become five of the largest construction firms in the world.

Connecting Markets: China as Global Trade Hub

There is a more farsighted aspect to BRI that goes beyond debt leverage and domestic overproduction: the project endeavors to situate China at the center of a new global economy that will characterize trade flows for decades if not centuries. As such, the BRI infrastructure projects that tend to receive the most ardent support from state-linked entities are those that form new spokes connecting back to the hub of the Chinese economy. One example is Pakistan’s Gwadar Port, which represents a maritime link to Xinjiang that can circumvent the choke point of the Strait of Malacca; another is the vast network of roads and railways that with every passing year draws the economies of Southeast Asia ever closer to China. This objective of creating new hard infrastructure links echoes the large body of literature illustrating how such connections can boost overall trade volumes and facilitate industrialization, particularly when a region suffers from a severe infrastructure deficit (which is widely true of BRI members). ‘Soft’ barriers, such as incompatible or inefficient legal and regulatory frameworks, can also act as impediments to cross-border trade flows, and high-level official speeches often ascribe as much weight to the importance of establishing ‘soft connectivity’ through the harmonization of cross-border frameworks as to the building of hard infrastructure itself.

Europe was always a natural target for greater connectivity given its importance as an export market, and early efforts to establish a direct rail corridor under BRI are now reaching fruition. The link is composed of two routes at various stages of completion.  The first of these is the Northern Corridor, which is essentially Russia’s Trans-Siberian Railway extended to link up with Beijing and Dalian. Second is the Central or Middle Corridor which runs from Lanzhou in central China and through the Kazakh ‘dry port’ of Khorgos, where cargoes must be offloaded to account for different rail gauges, before branching northward to the Russian route or southward to join up with the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR) joining Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey via the Caspian Sea. This southward branch has seen its appeal boosted since the outbreak of the Ukraine war as European shippers seek to avoid traversing Russian territory for fear of sanctions. The portion could be expanded further to incorporate Iran in the future, improving transit times by bypassing the Caspian Sea crossing and potentially even linking up with the India-championed International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC).

The first of these is the Northern Corridor, which is essentially Russia’s Trans-Siberian Railway extended to link up with Beijing and Dalian. Second is the Central or Middle Corridor which runs from Lanzhou in central China and through the Kazakh ‘dry port’ of Khorgos, where cargoes must be offloaded to account for different rail gauges, before branching northward to the Russian route or southward to join up with the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR) joining Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey via the Caspian Sea. This southward branch has seen its appeal boosted since the outbreak of the Ukraine war as European shippers seek to avoid traversing Russian territory for fear of sanctions. The portion could be expanded further to incorporate Iran in the future, improving transit times by bypassing the Caspian Sea crossing and potentially even linking up with the India-championed International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC).

The creation of the Eurasian Land Bridge cast China’s BRI in a primarily facilitating role: offering finance and diplomatic impetus for modernizing, harmonizing, and joining up pre-existing national rail networks. These efforts are now paying off, evident in the total 40,000 China-Europe freight trips on a route that prior to 2011 did not functionally exist. In 2021 alone, the China Railway Express (CR Express) – the callsign under which over 50 Chinese cities are connected to 24 European countries via 82 routes – operated over 15,183 trains carrying 1.46 million TEUs of cargo.

A similar process is unfolding in Southeast Asia, although the region’s pronounced infrastructure gap has forced BRI to play a more active role in financing and building new transport lines. Examples include Laos’ transborder railway connecting Vientiane with Kunming; the extension of said railway onward to Bangkok (expected to be completed in 2028); Cambodia’s toll expressway linking Phnom Penh and Sihanoukville (incidentally the site of a rumored future PLA Navy base); and Malaysia’s East Coast Rail Link (ECRL). In addition, plans exist to bridge the Thailand rail system with that of Cambodia and (even more ambitiously) Malaysia, along with a planned modernization of Vietnam’s Lao Cai-Hanoi rail link connecting the capital to China’s border. The overall vision for Southeast Asia mirrors that of the Eurasian Land Bridge: an interconnected regional transit system moving goods and people, with China forever at its core.

Conclusion

In light of the above, it would appear difficult to argue that BRI has not been a major success: the initiative has increased China’s diplomatic influence, stimulated growth internally and externally, and helped to ensure China’s ongoing centrality in regional trade networks for decades if not centuries. Yet a final determination cannot be made without embarking on a closer look of the risks that Beijing has taken on in pursuit of these goals. That will be the topic of the next article in this series.

*This article was originally published on September 21, 2023.

The post Belt and Road at 10: A Paradigm Shift in Development Finance? appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Strategic Commodities 2.0: Global Platinum Supply & Demand appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>Properties and Applications of Platinum

Platinum is recognized for its superior corrosion resistance, high melting point, and exceptional catalytic properties. Its primary utilization is in the automotive industry and other industrial sectors. Platinum-based catalytic converters play an essential role in reducing vehicle emissions, marking its contribution to environmental conservation. Moreover, platinum’s use in manufacturing processes, electronics, and diverse industrial applications accentuates its economic significance.

The post Strategic Commodities 2.0: Global Platinum Supply & Demand appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Regional Bank Collapses Complicate Fed Outlook appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

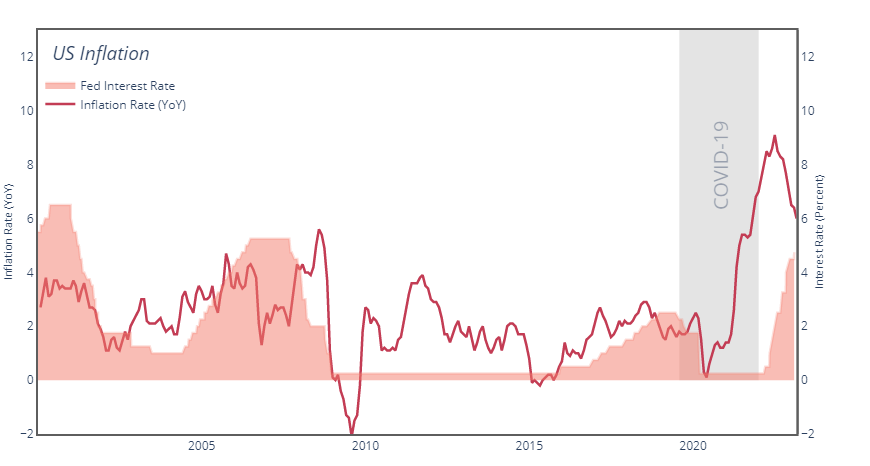

Events last week provided a stark illustration of how the Federal Reserve’s planned escape from post-Covid inflation remains anything but straightforward.

The Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), a California-based regional lender that focused operations on venture capital firms and tech startups, was taken over by US regulators last week after it proved unable to cover mounting client withdrawals. The episode unfolded as a textbook bank run: as soon as there was blood in the water, withdrawals soared as high as $42 billion on Thursday alone, forcing management to liquidate the bank’s already paltry reserves.

The post Regional Bank Collapses Complicate Fed Outlook appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>