The post Dedollarization and the Wane of Western Sanctions appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Dedollarization and the Wane of Western Sanctions appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Outlook 2021: Asia’s Path to COVID-19 Recovery Runs through Regional Trade Deals appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>At first glance, China looks to have stepped in to fill the void, seizing the opportunity to extend its influence and become a regional economic rule-setter. Upon signing the RCEP, Premier Li Keqiang said the deal was “a victory of multilateralism and free trade,” using language more often associated with the United States. Yet China will not be the sole beneficiary. Asia-Pacific countries hope the CPTPP and RCEP will encourage economic integration and drive growth as the region looks to recover from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dynamic Southeast Asian economies, four of which are members of both deals, are well-placed to benefit from the combined effects of CPTPP and RCEP in pushing down tariffs and liberalizing regional trade over the coming years. Aside from China, other stronger economies on the periphery, such as Japan, Australia and a small cohort of Latin American nations, are set for more marginal gains. The more difficult question is to what extent the United States, outside of both agreements as Biden takes office, is set to fall behind the curve.

The post Outlook 2021: Asia’s Path to COVID-19 Recovery Runs through Regional Trade Deals appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Why Protectionism Could Not Solve Trump’s Trade Deficit appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

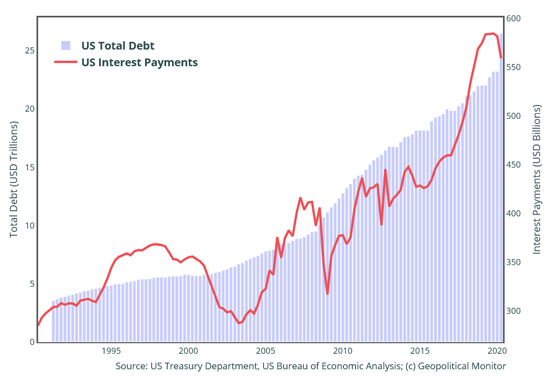

]]>Reagan began his presidency with $965 billion in debt, and ended it eight years later with $2.74 trillion, a trend ushered in by Reagan that would continue throughout the next five sitting presidents. George H. W. Bush elevated the national debt further, bringing it to $4.23 trillion by the end of his four-year term. This increase ebbed slightly following Bill Clinton’s election with the federal debt rising to $5.77 trillion after his eight years in office. Owing to the “War on Terror” and subsequent military and security expenditures, President George W. Bush more than doubled the national debt, bringing its total to $11.1 trillion after his two terms. Although President Barack Obama’s rise in federal debt failed to maintain the same pace as his predecessors, he still left office in 2017 with over $19.85 trillion in debt. National debt growth under Obama is, however, quite misleading with the “Great Recession” having significantly impacted the national deficit even before Obama assumed office.

Donald Trump took office in 2017. During his four years as president, he will have added $6.6 trillion in deficits and was originally projected to add approximately $8 trillion despite having been elected on the promise of reducing or eliminating the US trade deficit. His total deficits are tightly intertwined with the global pandemic and the US’ response through Trump’s declaration of a state of emergency and Congress passing the $2 trillion CARES Act, in addition to a number of other stimulus measures deemed essential for the protection of the US economy, though the spending outcome may have been different had the US federal government planned differently. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated these factors would have a deleterious effect on the federal deficit. Trump’s skyrocketing deficits can, to a considerable degree, be accredited to external forces and their impacts on the United States. Trump, nonetheless, lost his battle with the national deficit and has failed to secure a second term during which he may have been able to follow through on this original election promise or immerse the US deeper in debt.

The trade deficit emphasized throughout President Trump’s campaign became an avowed reason as to why the US economy was slowing down and the unemployment rate was increasing. Trump, in true political fashion, promised to reduce the trade deficits by attacking China and many key US allies in an effort to save US jobs and enhance the economy. Although he has kept to his word and “attempted” to decrease the deficit, it has been to no avail and instead resulted in ballooning the deficit even further. This may be due to his position that by attacking his closest allies and imposing tariffs on many Chinese, Canadian, and Mexican products, he would solve his woes. We detail firstly how the deficit has been growing as a result of an increase in the US’ purchase of foreign products and Trump’s decision to cut taxes, which consequently have resulted in inflating the national debt even further and forcing the US to borrow more from foreign investors to fund its consumption. We then articulate that Trump’s use of tariffs has been sorely misguided and has only served to magnify the trade deficit rather than mending it, resulting in, again, the national deficit increasing astronomically under Trump’s rule.

Ballooning the Trade Deficit

One of President Trump’s first promises after being sworn into office was to both cut taxes and to “Make America Great Again” by getting US citizens back to work by limiting the mass importation of goods that could be produced within the country, such as automobiles. Within one month of his presidency, he had stopped a Ford automobile plant from moving to Mexico, and “saved” thousands of jobs at its original factory in Michigan. Later, he signed the Tax Cut and Jobs Act which legislated an approximate $1.5 trillion tax cut that saw a 30% reduction in the corporate tax alone. With these two fiscally conservative actions, Trump instantly became a national “hero” to many. He subsequently reduced the unemployment rate to a record 3.9%, energized the economy, helped appreciate the US dollar – or increase the dollar’s buying power on the international market – and facilitated the boost in production of US goods to aid in the decrease of their consumption of foreign products. Looking at these statistics alone would lead many people to the understanding that Trump’s economic policies, explicitly his increase in ad valorem tariffs – that increase the price of a product by a fixed percentage – resulting in a trade war with China and his surrounding allies would work, right?

When the US economy was booming in 2019 and the unemployment rate was at its lowest point since 1968, it was expected by many of Trump’s supporters that his promise of decreasing the trade deficit would come true, but instead, they saw it ballooning even further. This is due to firstly, President Trump’s narrowly minded fascination with solely the current account in the US balance of payments, while seemingly ignoring the capital account though it is of equal importance. The balance of payments (BoP) is essentially a list of the transactions that flow in and out of the US. The BoP is split into two sections, the capital account, which is the flows of capital – often times seen through foreign direct investment – and the current account, which encompasses imports and exports. The capital and current account should always balance out to 0. Due to th e ongoing trade deficit in the US, this means that the country is importing more than it is exporting and thus, running a current account, or trade deficit. The current account deficit, in turn, requires the capital account to run a surplus to maintain the balance of payments, meaning that there are large flows of capital coming into the country in the form of investment. With President Trump’s decision to slash taxes and implement de-regulation amongst corporations, he created an atmosphere that resulted in more foreign firms entering the US market because of low-tax incentives. By bringing in more foreign firms he has consequently increased the capital account surplus. which inherently implies a current account deficit. By explicitly ignoring the US capital account, he limited his administration’s ability to decrease the trade deficit and has in fact, exacerbated it.

e ongoing trade deficit in the US, this means that the country is importing more than it is exporting and thus, running a current account, or trade deficit. The current account deficit, in turn, requires the capital account to run a surplus to maintain the balance of payments, meaning that there are large flows of capital coming into the country in the form of investment. With President Trump’s decision to slash taxes and implement de-regulation amongst corporations, he created an atmosphere that resulted in more foreign firms entering the US market because of low-tax incentives. By bringing in more foreign firms he has consequently increased the capital account surplus. which inherently implies a current account deficit. By explicitly ignoring the US capital account, he limited his administration’s ability to decrease the trade deficit and has in fact, exacerbated it.

Secondly, the US has exhibited a rise in US consumption as a direct correlation to Trump’s economic policies because of the resulting increase in per capita income. According to the determinants of demand, when a states’ average income rises and their currency appreciates, consumers in the US are expected to spend more money and concurrently, buy more products that are usually from abroad due to both their increased access to capital as well as the higher buying power of the US dollar. This has remained true in the US even with its recent mercantilist economic policies that attempt to stop the consumer from purchasing foreign products and instead, keep their money in the country. However, due to the relatively low-cost of foreign products, such as those imported from China, Americans found that they are consuming more imported goods, only aiding in the deficit increasing.

Trump misguidedly failed to exhibit the understanding that in order to cut the trade deficit, he not only should be concerned about the importation of products, but more importantly the spending habits of the American populace. In order to fund the American citizenry’s increase in consumption, the US government is forced to borrow more from abroad – often times from either China or Japan – resulting in capital flowing back into the country through the capital account. This, again, helps to balloon the trade deficit because in order to maintain an equilibrium of the balance of payments, the US is forced to run a current account deficit. Thus, due to the increased consumption by US citizens, the US is forced to borrow more capital from foreign investors, increasing capital flows into the country and aggravating the one thing that Trump said he would minimize – the trade deficit.

Why are Tariffs Not the Answer?

Even in the 18th century, when Adam Smith was composing the Wealth of Nations, economists were becoming well-aware of the negative effects that tariffs had on a state’s economy and that they were not beneficial in the long-term for the country and should simply be avoided. Although Smith, similar to Trump, believed that a state should, writes Douglas A. Irwin, “diminish as much as possible the importation of foreign goods for home consumption, and to increase as much as possible the exportation of the produce of the domestic industry,” he would surely disagree with how Trump sought to diminish the amount of imports the US obtains. Smith recognized that although tariffs were beneficial in the short-term because they increased employment and output in certain sectors that received protection, they were detrimental in the long-term owing to the fact that they would eventually result in a monopolistic dictatorship and prevent free trade from occurring, causing consumers to be charged higher prices for goods due to the loss of competition.

Although many economists after Smith have elaborated on his idea of free trade, he was one of the first economists to truly comprehend the detrimental effects that tariffs can have on a country, and instead pushed for free trade policies that allowed a state to pursue its absolute advantage in a product. Absolute advantage meant that a state should specialize in the production of a certain good that they can produce the most efficiently and then expand production to trade with other countries. Trade then becomes mutually beneficial for all parties involved because both resources and labour are allocated more efficiently in the production of the goods in comparison to if the US, for example, attempted to produce all the goods its populace required. If a state chose to implement a tariff, in comparison, production of certain goods would have to be increased past a corporation’s efficient capacity, resulting in the good not being produced as aptly in the home country as it could be abroad. Tariffs, although are a deterrent to consumption, do not completely disqualify a particular good from the market, resulting in many goods with tariffs still being purchased by the consumer. The consumer is then forced to pay a higher price for the good because of the tariff, due to the higher market value. The American populace, because of the implementation of tariffs on certain imports, would then have to pay for these tariffs out of their own pockets given that the producer forces the financial burden from themselves to the consumer, effectively harming citizens at home instead of the intended foreign corporation.

Although consumers in the US have been financially burdened because of the implementation of tariffs on a high quantity of the goods they demand, we saw the US going through a period of increased employment as well as greater production in certain sectors, such as manufacturing, because of the implementation of tariffs that are protecting American industries and allowing them to hire more workers. This, of course, all came to a grinding halt with the onset of the COVID-19 global pandemic and its impact alongside the government’s anti-pandemic measures that have had a debilitating effect on Americans and the citizens of many other countries. Despite their exceptionally brief benefits, these tariffs have also resulted in reciprocal “tit for tat” tariffs being added to US goods, such as the 25% ad valorem tariff on soybean products being imported to China. These retaliatory tariffs, in turn, have caused soybean farmers in the mid-west to struggle finding buyers for their produce and has hurt the economies of states such as Tennessee where soybeans are one of their largest exports. Smith, in comparison, did believe that tariffs were beneficial if they were used in a retaliatory fashion, which China has showcased, but this was the only exception and should be only temporary in form as it can complicate the use of free trade and can hamper a state’s progress in the importation of goods due to the increase in price per product. Thus, free trade should be pursued unless such extremely specific circumstances arise, because although tariffs can assist with defending certain industries by providing them protection in the international market, such protection will eventually stimulate a boomerang effect and be at the detriment to the whole state, demonstrated when Smith contended, “the gain of the town is the loss of the country.”

What Now?

In his article, “Why the Trade Deficit is Getting Bigger – Despite All of Trump’s Promises,” David Lynch stresses the fact that Trump misled the American populace into believing that tariffs on foreign products would solve the inherent “problem” of the trade deficit, when in fact, the US economy would suffer extraordinary setbacks in the future due to Trump’s protectionist policies. Lynch asserts that cutting taxes as well as “removing Congress’ limitations on government spending” culminated in the economy growing and consumption increasing, effectively ballooning the deficit even further. Trump’s realization that his protectionist p olicies have ballooned the deficit forced him to seek out other opportunities to reduce spending that the trade deficit has exacerbated. Trump then announced cuts to government spending while assuring the US populace that Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, three institutions that encompass 60% of the national budget as of 2015, would not receive cuts and that the military would only receive a small reduction in spending from $716 billion to $700 billion. These reductions, or lack thereof, could hardly affect the $21.7 trillion government deficit and were destined instead to continue to grow the deficit because of the increased expenditures Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security require due to the aging population of the US. As well, much of Trump’s voter-base is comprised of middle-aged and elderly people who depend on the welfare state and therefore limited Trump’s ability to cut these programs if he hoped to be re-elected in 2020. Thus, the only other viable way to limit the trade deficit would be to increase taxes to lessen the amount of borrowing from foreign investors, which would in-turn decrease the capital account surplus that would then allow the current account to balance with a less severe deficit. However, Trump was never likely to capitulate to this necessary evil.

olicies have ballooned the deficit forced him to seek out other opportunities to reduce spending that the trade deficit has exacerbated. Trump then announced cuts to government spending while assuring the US populace that Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, three institutions that encompass 60% of the national budget as of 2015, would not receive cuts and that the military would only receive a small reduction in spending from $716 billion to $700 billion. These reductions, or lack thereof, could hardly affect the $21.7 trillion government deficit and were destined instead to continue to grow the deficit because of the increased expenditures Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security require due to the aging population of the US. As well, much of Trump’s voter-base is comprised of middle-aged and elderly people who depend on the welfare state and therefore limited Trump’s ability to cut these programs if he hoped to be re-elected in 2020. Thus, the only other viable way to limit the trade deficit would be to increase taxes to lessen the amount of borrowing from foreign investors, which would in-turn decrease the capital account surplus that would then allow the current account to balance with a less severe deficit. However, Trump was never likely to capitulate to this necessary evil.

Trump’s efforts to “protect” US industry have resulted in increasing investment and capital flows into the country, while also ballooning the trade deficit and negatively affecting many US corporations that are now struggling under tariffs in addition to the added pressures of the global pandemic. With Trump’s inadequate knowledge of both basic international economic practices as well as the balance of payments of the US, his policies have effectively resulted in expanding both the trade deficit and concurrently the national deficit. To solve these ills, the Trump administration would have needed to either curb spending by a larger degree or limit capital inflows into the US through some alternative form that does not involve the enactment of tariffs. This would have then helped the current account’s deficit decrease by not being pressured as strongly by the capital account because of the enormous capital flows coming into the US. By decreasing the capital account surplus, the US would have inevitably seen a decrease in the trade deficit and overall, the nation’s deficit. Although Trump may have realized that drastic changes needed to be made to the US overall budget, he failed to act on any such awareness. Though the American populace will not have the opportunity to see how his fiscal policies play-out in a second term, Trump, based on his single-term performance, would have likely chosen ineffective policies and would have ended-up magnifying the national deficit further.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any institutions with which the authors are associated.

The post Why Protectionism Could Not Solve Trump’s Trade Deficit appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Post-Pandemic Supply Chains: Production Alternatives to China appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>America’s reservations and, in some cases, outright objection to China’s growing involvement in sensitive areas such as telecommunications and robotics is best exhibited through the Trump administration’s hawkish policies. Efforts like the increase in tariffs, the US-led campaign against Huawei, and the expansion of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) all serve as signals of a bifurcated global economy, pitting both powers against each other in a quest for economic supremacy.

Fears of such a scenario have only accelerated Beijing’s plans, as it seeks to independently fulfill its ambitions in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, aerospace & defense, and other sectors deemed critical to China’s technological prowess.

Yet China’s departure from low-cost manufacturing is not to be understood as a unilateral decision. Instead, Western leaders continue to pressure Multinational Corporations (MNCs) into redesigning their supply chains, shifting their overreliance on China in favor of repatriating manufacturing jobs to their home countries or selecting alternatives in the Asia Pacific (APAC).

With COVID-19 threatening to further impair the relationship between the West and China, the impetus to diversify suppliers and explore exit options has seldom been stronger, and even before the pandemic reached the United States. For example, President Donald Trump published a tweet seven months ago ordering US businesses to “start looking for an alternative to China.”

Such conditions present new opportunities for emerging markets in the APAC region to establish rival manufacturing bases for the China-weary. Of these options, India, Vietnam, and Myanmar possess the greatest opportunity to siphon off manufacturing activity from China.

The post Post-Pandemic Supply Chains: Production Alternatives to China appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post AfCFTA: Potential Problems for a Single-Market Africa appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post AfCFTA: Potential Problems for a Single-Market Africa appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post EU Inks Free Trade Deal with Mercosur appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>It took 20 years to the day for the two blocs to reach a trade deal, but the improbable finally occurred on June 28, 2019.

Hailed as a ‘truly historic moment’ by EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, the agreement will create a new market of over 770 million people. In Europe it’s being viewed as a victory for manufacturers, especially vis-à-vis their US competitors; in South America, it represents lucrative access to a market worth 3.4 trillion euros.

Here’s what’s on the deal:

The post EU Inks Free Trade Deal with Mercosur appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post US-China Trade War: Making Up Is Hard to Do appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>But a truce isn’t peace, and that has been reflected by the political maneuvering in both Washington and Beijing as the two governments prepare for the next round of trade negotiations. Which begs the question: What’s going on?

While this temporary armistice may have been struck in Buenos Aires during the G20 Summit, the origins of the US-China trade war goes way back to predate Trump’s populism or Xi’s imperial governance.

Trade relations with China, as well as many other Asian nations, for America, has always had more than just pure capitalistic benefit at heart. After all, it wasn’t until 1979 that the United States even established ‘normal’ economic ties with the Chinese. Up until Richard Nixon’s attempts to thaw relations during the Vietnam war, and President Deng Xiaoping’s liberalization of economic policy, the U.S. position on China had remained the same: passive containment. But it lacked heart, particularly in the face of greater foes such as the Soviet Union. In some cases, like with the Nixon Administration, Washington even viewed China’s contentious relationship with Moscow as potential shrapnel to be logged against the Kremlin.

In fact, the average American had a rather positive view of China as a result. In 1979, Gallup polling showed China’s favorability rating in the U.S. was 64%. In fact, up until the early 90s, China remained relatively popular, peaking at 72%. Even in the past five years, Uncle Sam’s Pacific neighbor has hovered in the 45% approval range back home.

Hoping to avoid conflict while still spreading Western concepts of economics and governance, much of America’s reasoning for a purposefully lax trade policy with China was the hopes that the connection would lead Beijing into the 21st Century as, at the very least, a neutralized threat. And to an extent, it worked. In 2001, the United States even backed China’s entrance into the WTO. But perhaps in an ironic twist to the US foreign policy of self-preservation and human rights, these initiatives designed to push China toward a freer market worked a little too well.

There’s even a term for it: Red Capitalism, which also happens to be a book written by Fraser J. T. Howie, a researcher who’s conducted extensive studies on China’s maneuvering in international markets. When asked about the recent truce, Howie told the Washington Post in an email “Markets should be happy, in that the worst is postponed. But I don’t see the West ever going back to business as usual with China. Too many genies have been let out of bottles.”

China took advantage of the open-door policy given to them by the United States in trade and used it to their advantage. Trade between the two nations reached $211.6 billion in 2005, compared to the $2.4 billion exchanged in 1979. From 2001-2005, the volume of US-China trade increased an average of 27.4 percent a year. As a result, the United States has become the top market for Chinese merchandise and China is buying up more U.S. goods, with U.S. exports to China rising 21.5 percent in each of the last four years.

But China hasn’t been the only one utilizing these open markets. By 2030, it’s expected that US exports to China alone will be a staggering $520 billion, according to a report from the US-China Business Council. To put that into perspective, the combined trade between Beijing and Washington in 2017 was worth $710 billion dollars. The United States has continuously operated as a high-value trade partner for the Chinese, providing trucks and construction equipment, which totaled profits of $6.7 billion in 2014 and $7.1 billion in 2015. US exports to China made 1.8 million new jobs and $165 billion in GDP in 2015 according to the same report.

Overall, while cheaper Chinese products have created a damaging trade deficit and led to the dissolution of countless U.S. jobs over the years, it’s also necessary to note that this imbalance hasn’t been without its positive effects. It’s estimated by the US-China Business Council that the flood of cheaper products have lowered overall prices in the marketplace by around 1.5%, which when taking into consideration that the average family in the states made $56,500 a year in 2015, means that this trade balance saved these families around $850 a year.

The reasons behind this trade deficit of $335.4 billion are rather straightforward and simple: American businesses’ reliance on cheaper Chinese products have led to the U.S. importing more than it exports to Beijing.

Many argue that the main reason for the economic imbalance between these two superpowers – China’s overall cheaper pricing – is purely an artificial ploy by the government. By devaluing the yaun, China’s currency, at a rate of 40%, Beijing has kept it below free-market levels. While China did agree in 2005 to a 2.1% increase in the yaun’s value, it pales in comparison to the work needed to restore the currency to normal levels, a claim backed up by the director of the Institute for International Economics, C. Fred Bergsten, among others.

Strangely enough, unlike the vast majority of issues that face the United States, the problem of trade with China is a matter that draws bipartisan support. A recent UBS poll shows that 71% of U.S. business owners want a tariff increase on Chinese products, a belief shared by 59% of high-value investors in the same survey. Even politicians seem to agree on the issue for the most part.

“China’s refusal to play by international economic rules cripples our ability to compete on a level playing field.” Sen. Chuck Schumer, current Senate Minority Leader said back in 2006. Republican Lindsey Graham (R-SC) sponsored a bill in that year that would have levied a 27.5 percent tariff on all Chinese imports unless the yuan was significantly revalued. However, the bill never made it to President Bush’s desk, as it was withdrawn in March after the two lawmakers visited Beijing.

President Trump’s surprise victory in November of 2016 shook the dynamic of this decades-old relationship to its core. His populistic rhetoric and his position as the US champion of protectionism made some think that as a man, as an idea, he was unelectable. But Donald Trump didn’t invent the concept of ‘America First’ all by himself; he carefully utilized the seed of discontent that had been sowed years ago. His talk on China had always been tough, a mirrored reflection of much of his positions in general on the campaign trail.

“China is neither an ally or a friend — they want to beat us and own our country” – a tweet from Trump on Sept. 21, 2011.

“We can’t continue to allow China to rape our country and that’s what they’re doing. It’s the greatest theft in the history of the world.” – another from the campaign trail in May 2, 2016.

But when Trump made his first visit to the Chinese mainland early in his term, hints at a more moderate tone seemed to emerge. “I don’t blame China,” Trump said in Beijing. “After all, who can blame a country for being able to take advantage of another country to the benefit of its citizens?” But then, for a while, it seemed like maybe the 2016 candidate was back in the saddle.

Tariffs on products worth around $250 billion were levied on Chinese products by the Trump administration in 2018, with Beijing responding with tariffs of its own. But the G20 Summit resulted in some concrete results, with the Chinese Foreign Ministry confirming that the two leaders had instructed their teams to intensify talks. A truce in economic hostilities was also announced, a period to be accompanied by talks that should last around 90 days. A 40% decrease in Chinese tariffs on U.S. cars is also rumored to be in the works.

Yet some analysts argue that the issues go far deeper than just a trade deficit. Barclay’s Ajay Rajadhyaksha told CNBC in October at the Barclays Asia Forum in Singapore: “This is not the U.S. and NAFTA. This is not the U.S. and the European Union … There is a significant part of the US administration that is worried about China’s technology ambitions. The administration wants fundamental changes in how the Chinese treat intellectual property, how they talk to technology companies looking to invest in China. This is not about the trade deficit. If it was, it would be easy to solve.”

Saying that it’s almost impossible to come to any truly comprehensive conclusion on the full impact of the world’s most powerful trade relationship is an understatement, but it’s not hard to see that things have changed, and probably permanently. “Business as usual” isn’t a term we can accurately use anymore when talking about these two giants of the Pacific. The partisanship may continue, as well as the political hearsay, but the facts remain the same. A lot rides on the coming talks, and the impact they will have on the global economy is unpredictable.

I guess you could say: “it’s complicated.”

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect the official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any other institution.

The post US-China Trade War: Making Up Is Hard to Do appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Sino-Indian Relations: The Weak Point of the BRICS appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The BRICS grouping, which takes its name from the initials of its members (namely Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), includes the world’s most important emerging powers. Due to their dimension, economic growth, demographic size and (increasing) military strength, these five states are becoming more and more influential, often taking a leading regional role and even launching some global-scale initiatives. On paper, the grouping has the potential to fundamentally alter the international geopolitical landscape. In practice, however, there are serious challenges to overcome, mainly in the fundamental differences between BRICS countries in terms of configuration and polity and, most importantly, the group’s lack a unified vision. Sometimes, their respective projects can diverge. But in the case of India and China, they openly clash.

The post Sino-Indian Relations: The Weak Point of the BRICS appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Emerging Powers See Opportunities under Trump Doctrine appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>From pulling out of carefully negotiated multinational treaties and trade pacts, and showing a rather cavalier attitude toward key security alliances such as NATO, it should perhaps not come as a surprise when German Chancellor Angela Merkel bluntly observes that “the United States is no longer a reliable partner.”

But what about the rest of the world? How do smaller emerging nations who don’t hold security council seats or massive market power feel about the Trump doctrine? Do they see opportunities to advance their interests under these new rules, or are they as just as opposed to the risks of American isolationism as the major powers?

When the world’s largest nations bicker over how global relations should be managed, emerging markets tend to be ignored. That is a shame. After all, by 2030 developing countries will account for nearly 60% of the world’s GDP, according to the OECD calculations, and one would assume they have an opinion about how the international system should be structured.

The election of President Trump has been accompanied by unprecedented changes to this system, moving the United States away from the “sticky power” of institutionalism, multilateralism, and interdependency, and back toward something more resembling great power politics, a zero-sum vision that does not prioritize rules or norms. President Trump’s administration appears to have much more in common with Vladimir Putin’s worldview than with Bretton Woods or the World Trade Organization – and this trend is not going unnoticed by leaders from Latin America to Africa and Southeast Asia.

So how does this new doctrine change an emerging country’s growth strategy? For one, there are short-term political consequences for factions which had prioritized close relations with Washington and the West. For many establishment political figures who staked their reputations on the fruits of alliance with the US, this is a disappointing moment.

In the coming years, there is going to be a lot of talk about adopting alternative models to achieve growth and prosperity which are untethered from the values that used to be promoted across international institutions. On the one hand, nearly everyone we speak to from Buenos Aires to Johannesburg to Dhaka is in awe of China’s rise, expressing open admiration for their agility to adopt a cooperative developmentalist approach to their regions, one that was already challenging the US model for primacy – even before the Muslim bans, wall proposals, and unflattering comments about Africa.

As the United States retreats from global leadership, many have commented that China will capture the spoils – though in many ways that was happening already. What is more important is after decades spent by the US and other international institutions educating smaller nations about the need to trade within WTO rules, to establish rule of law and basic political and economic freedoms, and meet certain fiscal and policy standards to achieve stability, now all of that seems to have evaporated overnight.

Some leaders, of course, will be delighted to be freed of these constraints. Under the Trump doctrine, they are likely to express a broader range of discretion in how they manage domestic affairs – with a more carefree attitude toward compliance with international standards on human and political rights. There are numerous sweeping changes that come part and parcel along with extremist visions of sovereignty above all else.

Just this week, President Trump’s National Security Advisor John Bolton ordered the Washington DC office of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) to be shuttered, and unleashed a withering attack on the International Criminal Court (ICC) that would sound very familiar in Kampala or Khartoum. In Guatemala, a highly successful UN-based anti-corruption commission is on the verge of closure, and crucial international support to keep it open is plainly lacking.

To the developing world, this shift is dizzying. Democracy promotion, open economies, climate change were America’s priorities. Now, nations in the developing world are forced to reassess their options vis-a-vis the ‘new America.’ And, in this brave new moment, non-Western powers and systems are beginning to look more attractive by the day.

But the Trump doctrine also features negative aspects for emerging countries, especially for certain geostrategic locations where they could manage a swing position between the US, Russia, and China depending on the interests of the day. Now, stuck with fewer choices, these leaders are very well aware of Beijing’s agenda. From the predatory lending and enabling of corruption to acts of territorial aggression, industrial espionage, and rampant intellectual property theft, there are known risks that come with a dependent relationship with China.

Beijing’s charm offensive largely seeks to hide these patterns under a rhetoric which oddly parrots the former international order promoted by the West – celebrating inclusivity, cooperation and mutual benefit, while conveniently avoiding issues like liberty and representation. President Xi’s willingness to recognize and promote a “community of common destiny,” illuminates the contrast with the United States.

This is unambiguously negative for US interests. In January, while Trump was requesting Congress to allocate funds for the US-Mexico border wall, China sent delegates to Chile, inviting Latin American leaders to participate in the Belt and Road Initiative. Months later, as Trump bullied US allies at the NATO summit, China was wrapping up the “16+1 summit” in Bulgaria, where Chinese investment and diplomatic relations were marketed to Central and Eastern European leaders. And most recently, Chinese President Xi Jinping wrapped up his travels throughout Africa, where he was visiting with heads of state and deepening China’s relationships with the continent of the future, while America picks a one-sided trade fight with Rwanda.

We are chronically overlooking the ground America is ceding in relations with the developing world. Not long from now, today’s ‘emerging markets’ will have emerged. As Angel Gurría, the OECD’s Secretary-General said: “the newfound prosperity in the developing world represents an enormous opportunity for citizens in the developing and developed world alike.”

The US has much to lose from the engines of tomorrow’s economy shifting their development strategies within China’s orbit. While we in the US recover from whiplash, let’s just remember that the rest of planet isn’t waiting for us.

Peter Schechter is a political analyst, author, co-host of the Altamar Podcast, and former founding director of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. He can be found on Twitter at @PDSchechter.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect the official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any other institution.

The post Emerging Powers See Opportunities under Trump Doctrine appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Trump Puts US-China Trade War on Pause appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The US-China trade war has been put on hold, with both sides claiming an early victory.

A week of high-level talks in the United States resulted in the Trump administration dialing back its threats of wide-ranging tariffs. The move comes days after President Trump called on the Commerce Department to ease penalties on Chinese telecom ZTE, which was faced with bankruptcy after a ban on buying US components.

It’s obvious what China gets here: a reprieve from a damaging US-initiated trade war and a chance to enter into open-ended negotiations, all without having to cross (or even approach) any of its negotiating red lines. What the United States gets out of the deal is far less obvious, a fact that has many of the hardliners in President Trump’s administration – and voter base – up in arms over what they view as an unforced capitulation from their tough-talking leader.

The post Trump Puts US-China Trade War on Pause appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>