The post State Backers in Middle East Proxy Conflicts appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>Over the past decade or so, conflicts in Syria, Yemen, and Iraq have witnessed the engagement of Iran-backed militias, resulting in US soldiers encountering combat, security threats, and fatalities. The involvement of Russia and China often exacerbates the chaos, with China extending economic and diplomatic support, while Russia offers economic and military backing. Examples include China emerging as the primary benefactor of Iran and Afghanistan, as well as establishing normalized relations with the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and accrediting the Taliban ambassador in Beijing. Additionally, Russia, besides supplying weapons, has deployed troops through entities like the Wagner Group and other private military companies (PMCs), backing various militias and parties entangled in these conflicts.

The interests of various external powers often converge, leading to alliances. For instance, both Israel and the United States share an interest in opposing Hamas and Hezbollah. Another example is the United States backing a coalition led by Saudi Arabia in Yemen, while the opposing side receives support from Russia and Iran. Additionally, Russia supports President Bashar al-Assad, while the United States and Saudi Arabia support Syrian opposition forces.

The post State Backers in Middle East Proxy Conflicts appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post The Geopolitics of the Central Caucasus appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>There were reasons why it evaded the notice of many, but first and foremost, we should mentally map the area. The Central Caucasus, comprised of Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, is a historically constructed, complex political concord, embodying a geopolitical tapestry woven over centuries and forming a culturally, ethnically, linguistically, and religiously diverse area stretched between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea.

In the geopolitical discourse, as explained by Saul Bernard Cohen, an eminent American geographer, the axiom stands firm: “Geopolitics is a product of its time.” Each historical period has produced a geopolitical model offering a lens through which to interpret the world map and the world order of that time. In imperialist geopolitical writings of the 19th to early 20th centuries when a state’s greatness lay in its maritime power and/or in domination of the Heartland (the territory ruled by the Russian Empire and later by the Soviet Union), the distance of the Central Caucasus from the Anglo-American space resulted in little to no mention of the region.

Whilst the strategic location of the Central Caucasus temporally escaped the attention of imperialist writers, historically, the region carried geopolitical importance for three major Eastern powers: The Persian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Russian Empire. Already in the early 1800s, the region acted as a buffer zone between Orthodox Christianity and the Muslims of the Middle East. Russia’s expansion into the Caucasus in the sixteenth century additionally carried economic considerations, evident in projects like the Trans-Caspian railway, which facilitated access to Central Asia and control over Caspian oil supplies. Next to its geographical advantages, the Central Caucasus was a boon for natural resources. Besides Petroleum, the region is rich in copper ore. The minerals also attracted foreign investors and as of 1870, Rothschild and Shell was extracting oil, while Siemens mined copper.

After World War II, the political picture drastically changed and a new international system emerged, with multipolarity giving way to bipolarity. During the Cold War, geopolitics became associated with the two leading ideologies of that time: Communism and Western Democracy. Geopoliticians, thus, were mostly preoccupied with the rivalry between the two blocs of the West and the East. When the Soviet Union established its rule over the Central Caucasian states, the region once again became extraneous to the interests of international observers and witnessed its geopolitical role as a bridge for regional and international trade routes reduced to serving the southeastern border of Europe with Communist Russia and the Middle East.

By the 1980s, however, “winds of change” were blowing on the Eastern side of the Iron Curtain, and with Mikhail Gorbachov’s policies of glasnost and perestroika, the Cold War was nearing its logical end, giving way to a new world order. Simultaneously, geopolitical concepts were updated to understand the new world map and where geopolitical pivots had moved, which came to be known as the New World Order in an academic context. While some rejoiced in triumph of the Western ideology and others coined a neologism “Geo-economics” to explain the substantial penetration of economics into geopolitics, a drastically different approach was undertaken by Samuel P. Huntington to explain the geopolitical setting and patterns of this “new world.” He emphasized cultural differences as the primary basis for identity and conflict, predicting that nations would align along cultural lines rather than ideological or economic ones, leading to conflicts at local and global levels. Huntington identified several fault lines, including the Balkans, the Caucasus, and the Middle East, as areas where clashes between civilizations were likely.

Now, in addition to its geographically determined strategic function as a buffer and bridge on two axes – West-East and North-South, the region’s ethnoreligious mosaic was also put under the spotlight of geopolitical works and international actors. Geographically situated between Orthodox and Islamic civilizations, the region has fostered a diverse ethno-religious mosaic. Despite religious differences, examples of religious tolerance can be found in cities like Derbent, Dagestan, and Tbilisi, Georgia. Additional emphasis is given to the role of customs, which in the Caucasus is referred to as ‘adat.’ It is argued that customs (or adats) in the region are stronger than confessions, and even contend for superiority over the latter. The custom-based relationship between the peoples of religion facilitated their peaceful coexistence, tolerance, and mutual understanding. The historical background of peaceful coexistence and distinct patterns of Caucasian, custom-based relations between different religions and ethnicities, provided the understanding behind the harmonious relationship between the Caucasian people.

The Russian Effect

The demise of the Soviet Union, however, did not mean the end of the Cold War rationale. Russia – as the heir of the Soviet Union – after disappointing the hopes of anticipated democratization was still considered a power whose influence had to be contained. Zbigniew Brzezinski, like many of his contemporaries and those before him, assumed that Russia at some point in post-Cold War history, whether voluntarily or not, would choose the path of Western development, a hope that remains unrealized to this day. The reasons behind this can be traced back to the Russian understanding of the world system, which has been incautiously neglected by Western academia and which is vividly illustrated by the Russian geopolitical school: Eurasianism. All important contributors to the development of Russian Geopolitics (Nikolai Trubetzkoy, Peter Savitsky, Lev Gumilev, Aleksandr Dugin) emphasized Eurasia’s distinct cultural-geographic and socio-historical pattern and rejected Western universal ideas of the cultural and historic development of mankind. It was believed that it was Russia’s mission to unify Eurasia and maintain this unity, asserting that it was the destiny of the Eurasian people to be concerted.

It is important to understand that Eurasianinism and Moscow’s approaches toward the Caucasus correspond to each other. In this regard, the Central Caucasus is considered as Russia’s backyard. Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia, the Black Sea, and the Caspian Sea constitute strategic dimensions for Russia. The latter is determined to dominate the region and uses the “ethnic card” to keep the countries of the Central Caucasus off balance. From the Russian standpoint, any foreign influence in its “near abroad” is seen through the prism of its national security. Such a menace should be thwarted by any means, as Moscow made clear more than once that it does not entertain any notion of conceding territories of its utmost geopolitical interests.

As the successor of the Soviet Union, Russia experienced the heaviest losses in terms of territory, resources, influence, economy, as well as international image. Its borders were pushed back from the west, south, and east. To add fuel to the fire, the divorce of the Central Caucasian states from Russian influence and the emergence of newly independent states in Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan with nationalist-minded political elites reinforced the fears of a resurgence of the deep-rooted Russian-Turkish rivalry over influence in the region. A prominent Eurasianist Alexandr S. Panarin argued, that “the geopolitical concessions which post-Soviet Russia made to the West are the maximum Russia will ever concede. Any further attack by the West Belt in the form of further enlargement of NATO or by playing the Ukrainian, Georgian, Azeri, or Central Asian ‘cards’ would mean that the aforementioned concessions by Russia were like the concessions to Hitler at Munich.”

Dominating the Caucasus for Russia also translates into being closer to the Mediterranean and Balkans. Some of the imperialist-minded politicians, such as Vladimir Zhirinovsky, expressed the ambition of obtaining access to a warm water port on the Indian Ocean. Needless to say, conceding the vital Caspian Sea resources it could potentially lose with the opening of the market to the west – along with flows of Western investment following the breakup of the USSR – would substantially weaken Russia.

The Caucasian Chalk Circle

In the context of the so-called emerging New World Order, Russia was at first left on the periphery, while Turkey and Iran were the first countries affected by geopolitical turbulence. Entering the ‘Mittlespiel’ of this ‘Great Chess Game,’ the United States and the European Union quickly exploited the opportunity to increase their influence in the region of the Central Caucasus. Hence the latter soon became a space of competition between original geopolitical players and so-called ‘newcomers.

Iran is one of the classical players in the Central Caucasus, however, due to its internal turbulence and international pressures, it was forced to temporarily retreat from the contest. The latest trends show the revitalization of Iran’s interests in the Central Caucasus. In the regional context, Iran is an ally of Armenia and Russia.

Turkey, as Brzezinski suggests, must not be alienated from geopolitical calculations, because a rejected Turkey can not only become strongly Islamic but will be able to upset the region’s stability. Turkey’s role in this contest, along with its geopolitical inclinations, is to counter-balance Russia’s domination over the region. That is why Brzezinski argues that political developments in Turkey and its orientation will be crucial for the states of the Central Caucasus.

The EU presence in the region is perceptible as well. In the framework of its Eastern Neighborhood Partnership, the Union encouraged countries of the region toward reform and as an accolade granted Georgia candidacy status. Furthermore, the location and the mentioned potential to provide transit roads allow Central Caucasus to serve as an energy security guarantee to Europe. In line with this, Europe needs to assist the region in its peaceful development and assure its security as a strategic partner.

Contrary to Armenia and Georgia, Azerbaijan does not openly express willingness to join either military or economic blocs. The country is neither pro-Russian, nor pro-Western, but emphasizes the importance of regional cooperation. Consequently, the countries are at different steps in the process of Europeanization. Nevertheless, the EU’s need for a reliable partner in the Central Caucasus is currently at odds with Turkey’s estrangement from the Union and Russia being non-responsive to sanctions.

The United States has long viewed the region, and especially Georgia as a strategic buffer zone to assist its interests in the Middle East, as well as against the expansion of terrorism. In 2016, Donald Rumsfeld, former US Secretary of Defense, highlighted the strategic location of Georgia in his article in The Wall Street Journal, by stating that “[Georgia] provides a barrier to the flow of jihadists from other parts of the former Soviet Union to the Middle East. And it will doubtless figure large in the strategies of any NATO consortium for securing the Black Sea and ‘New Europe’ against Russian adventurism.”

An additional newcomer to the regional chess game is China with its growing geopolitical influence, making the region’s importance even greater through participation in the Chinese Silk Road project and, since 2017, in the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route project.

The cultural dimension, specifically the ethno-religious factor, in a time of growing resurgence of nationalism and fundamentalism, is a factor directly influencing geopolitical considerations. Historical differences have shaped difficult relations between Turkey-Armenia and Armenia-Azerbaijan, leading to friendship between Russia and Armenia. Russia’s betrayal and mistreatment of Georgia has alienated the country from its northern neighbor, with whom it shares a common religion. Despite diverse religions, Georgia maintains a friendly relationship with Turkey and Iran, with the latter enjoying a somewhat positive attitude among all the Caucasian republics.

Its location and its experience as a borderland of various religions and ethnicities permit the region to be crucial in what is claimed to be the primary menace and security challenges of the 21st century- terrorism, further enhancing the Central Caucasus’s role as a border of civilizations.

As observed, the developments of the post-Soviet era brought new actors such as the US, EU, and China into the contest of imposing influence over the region, as well as extracting benefits from it. Such unfolding of events, however, runs contrary to the aspirations of the major neighboring geopolitical powers, such as Russia, Turkey, and Iran; the concentration of political interests of the great powers in such a small region emphasizes its favored geopolitical position and economic advantages.

Borrowing from Bertolt Brecht’s theatrical play The Caucasian Chalk Circle, the configuration of international interests in the region spotlights power conflicts. Such concentration of global powers in its turn shapes the foreign orientations of the countries of the Central Caucasus. In the realm of geopolitical discourse, a region can be geopolitically significant if it serves the geopolitical and economic benefits of major geopolitical players or has the potential to challenge such political-economic aspirations of great powers. The Central Caucasus, as a result of its strategic location and diversity, possesses both characteristics. Consequently, Central Caucasus stands amid a complex geopolitical landscape, and next to presenting economic opportunities for great powers, finds itself in the hotspot of 21st-century security considerations.

The post The Geopolitics of the Central Caucasus appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Sagging Real Estate and Bad Debts: China’s Banking System Risk appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The real estate crisis in China has been characterized by a slowdown in the market and declining property prices, placing financial strain on developers and homebuyers alike. Evergrande, the country’s largest developer, was ordered to liquidate last year after missing two years of payments on its $300 billion in debts. Similarly, Country Garden slipped into default while carrying approximately $187 billion in liabilities. About two-thirds of the remaining real estate developers have already defaulted or are facing defaults on upcoming payments. This downturn has direct implications for the banking sector, as real estate loans account for a quarter of bank loan portfolios. If the market continues to slump, defaults on these loans could jeopardize the stability of financial institutions.

The post Sagging Real Estate and Bad Debts: China’s Banking System Risk appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post China’s Economy Turning a Corner? appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>One event framed the political context of the first half of 2023 more than any other: the abrupt end of China’s zero-COVID policy. The first few months of the year saw hospitals and health services overwhelmed with the sick, and a population fearful of catching a virus that had been aggressively stigmatized by the state. COVID-related deaths rapidly mounted, though no one can be sure of the exact number given underreporting in the official data. Estimates of total deaths range from the hundreds of thousands to millions.

The post China’s Economy Turning a Corner? appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Geopolitical Snapshot: Nigeria appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

Nigeria’s geopolitical importance stems from its demographic, economic, and strategic weight. As the most populous country in Africa, with over 200 million people, Nigeria represents significant demographic power via a large domestic market and labor force. Furthermore, Nigeria’s diverse society, which encompasses a wide range of ethnic groups and cultures, places it at the heart of African socio-political dynamics, making it a critical player in efforts toward regional integration and cultural diplomacy.

Economically, Nigeria is one of Africa’s largest economies, with its approximately $395 billion GDP among the top three on the continent – higher than Egypt’s $358 billion and just behind South Africa’s $401 billion. The nation’s wealth is largely attributed to its extensive oil and gas reserves, making it one of the world’s leading oil exporters. Strategically, Nigeria’s location on the Gulf of Guinea grants it a pivotal maritime position, controlling crucial shipping lanes with access to significant Atlantic trade routes. This strategic maritime position is vital for international trade, especially for oil exports. Moreover, Nigeria’s role in regional and international organizations, such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the United Nations, amplifies its influence on regional security, economic policies, and diplomatic initiatives. As a leading contributor to peacekeeping missions in Africa, Nigeria has a substantial impact on the continent’s security landscape. Its efforts in combating regional threats, such as terrorism and piracy, further underline its importance as a stabilizing force in West Africa.

The post Geopolitical Snapshot: Nigeria appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post EU Opens Membership Talks for Bosnia & Herzegovina appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

Geopolitics in the Western Balkans

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s geopolitical importance in the Western Balkans stems from being at the crossroads between the East and West and the Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Islamic worlds, making it a melting pot of religions, historical influences, and cultures. This unique position has historically made it an area of strategic interest and competition among nations.

While Bosnia and Herzegovina has a very limited coastline, its proximity to the Adriatic Sea, positioning near major sea routes and ports in the region enhance its strategic importance, especially in terms of trade and military mobility. The country’s complex ethnic and religious demographics, consisting of Bosniaks (primarily Muslim), Serbs (primarily Orthodox Christian) and Croats (primarily Catholic), reflects wider regional diversities and tensions. The interplay of these ethnic groups within Bosnia and Herzegovina is a microcosm of the broader Balkan dynamics, influencing peace, stability, and relations in the region.

The dissolution of Yugoslavia in the 1990s gave rise to the Bosnian War (1992-1995) and the subsequent establishment of the independent state of Bosnia and Herzegovina with the Dayton Agreement. During this period, Russia supported the Serb population in Bosnia, particularly those who sought to maintain closer ties with Serbia and Russia.

Since the 1990s geopolitical rivalry over the area has intensified. The ongoing war in Ukraine has worsened already tense relations between Russia and Western countries, contributing to increased tensions in the Balkans.

Over 20 years since the conflicts in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Yugoslavia), the institutions established to manage the diverse demands of various ethnic and religious groups are showing signs of instability. As a significant part of this region strives for closer ties with the EU and NATO, Western governments believe that Moscow is exploiting existing tensions to obstruct these foreign policy aspirations.

The situation shifted recently, as the invasion of Ukraine arguably weakens Russia’s influence in the Balkans. This presents a chance for Western nations to renew their engagement with the area.

Russia’s Interests in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Efforts to integrate Balkan countries into Western organisations have faced steady opposition from Russia and nationalist and separatist forces in those areas, especially given the ongoing threat of unresolved disputes in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as between Serbia and Kosovo.

In European nations, where political structures are significantly more robust, the rise of xenophobia and populism is causing upheaval, making the Kremlin’s support for far-right and authoritarian-leaning leaders in the Balkans a cause for concern. Russia’s actions are likely to promote a regression in democratic practices and increase political divisions, both of which pose challenges to the ambitions of Balkan countries wanting to join the EU and NATO.

The Kremlin’s strategy in the Balkans serves as a distraction, diverting Western attention from Russia’s more concerning manoeuvres elsewhere, such as the military escalation in the Sea of Azov, the deteriorating conflict conditions in eastern Ukraine, the advancing boundary line in South Ossetia, and Moscow’s covert influence campaigns in post-Velvet Revolution Armenia. For Russia, engaging in the Balkans is a tactic to shift focus away from these activities and to impact wider European security and economic structures.

Energy, investments, business deals and military cooperation all serve as key economic vectors for Russian influence in the Western Balkans. The effective use of energy as a means of diplomacy showcases the critical importance of fossil fuels within the Russian economy. Moscow has consistently aimed to minimize its dependence on Ukraine for gas transit, favoring Southeastern Europe as an alternative route. This strategy has also involved making several European nations reliant on Russian natural gas.

Russia has supported Bosnian Serb separatist movements both formally, via the Republika Srpska, and unofficially, through various cultural, religious, educational, and paramilitary organizations. Moscow has increased its backing for Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik, who has promised to secede the Republika Srpska from the national institutions of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Russian arms dealers have provided weapons to the police forces of the Republika Srpska, and Russian mercenaries have offered training to members of Bosnian Serb paramilitary units.

In Bosnia, Russian financial engagement is primarily directed through the Republika Srpska, a Serb-majority region, as a means for Moscow to exercise influence over Bosnia’s political direction. These investments have positioned Russia as the fifth-largest foreign investor in Bosnia. However, not all of Russia’s promised investments materialized or made profits. For instance, Russian billionaire Rashid Sardarov whose offshore company based in Cyprus has control over at least five energy enterprises there, committed to investing 800 million euros in the Republika Srpska in 2011. One of the thermal power plants he vowed to construct, planned for completion in 2017, has been indefinitely postponed.

NeftGazinKor, a company owned 40% by Russian oil company Zarubezhneft, manages oil refineries in the Republika Srpska towns Brod and Modriča, marking Russia’s most significant investment in Bosnia to date. Despite incurring losses of about $60 million since 2016, these refineries remain operational, indicating that Moscow values strategic influence in the Republika Srpska over direct economic returns. These ventures not only secure jobs for Bosnian Serb refinery workers and foster favorable opinions toward Russia but also enable Republika Srpska leaders to showcase their alliance with Moscow and possibly own the stakes in the company.

Furthermore, Russia is represented as a crucial financial supporter of the Republika Srpska beyond just the energy sector. High-level discussions have been held between senior Russian officials and Milorad Dodik. Following the enforcement of Western sanctions on Dodik for organizing a 2016 referendum that breached the Bosnian Constitutional Court’s ruling, reliance on Russia has intensified. Since then, Russia financially supports the Republika Srpska and Milorad Dodik with hundreds of millions dollars of grants and loans.

Milorad Dodik is often a guest of Russia and has had meetings with President Putin, and other high officials. Recently, in his interview the Russian Ambassador to Bosnia and Herzegovina, Igor Kalabuhov thanked Milorad Dodik for friendly and extensive cooperation between Russia and Republika Srpska. The Russian Embassy in Sarajevo is one of the largest and most equipped, and could theoretically steer unrest and support Milorad Dodik should the need arise in the future.

Serbia’s Interests in Bosnia and Herzegovina

A central component of Serbia’s foreign policy is duplicity, whereby Belgrade simultaneously aspires to EU membership and closer relations with NATO, while balancing relations with other major powers in the belief can profit from each.

Serbia’s policy towards the region has not changed since the departure of Slobodan Milošević. However, different means are now being employed, and they are largely placed in the context of current events in the relationship between the West and the Islamic world, especially concerning Bosnia and Kosovo. Still now, as 30 years ago, a proposal for the reconfiguration of the Balkans along ethnic lines emerges from circles of national ideologists.

Serbia’s geopolitical interest in Bosnia and Herzegovina is to preserve the Republika Srpska and work on its possible annexation to Serbia. It is geopolitically important for Serbia because of the geopolitical pressure on Montenegro and access to the Adriatic Sea, seizing the opposite bank of the Drina River, and shifting the “civilizational boundary” westward, which further projects Serbian influence.

In Serbia, Republika Srpska is treated as a state to defend the constitutional rights of the Serbian people and that has been internationally verified by the Dayton Agreement. The dissolution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, or the independence of the Republika Srpska, is a stated goal to which both EU membership and the essential national interests of Serbia itself are subordinated. Therefore, nationalists believe that binding Serbia to European integration would de facto tie Belgrade’s hands when it comes to providing assistance to maintain the Republika Srpska.

Serbia also has interests in the military industry of Republika Srpska. Through stakes in various defense companies, the Serbian government under President Vučić can finance production of equipment for the military, while supporting Milord Dodik and also potentially supplying the Serbia and Republika Srpska’s militaries.

There are interests in the energy sector as well, related to gas supply from Serbia and building new pipelines toward Banja Luka to secure energy supply to Republika Srpska. This project is supported by Russia; notably, the pipeline project will not cover other parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina especially Sarajevo, Travnik, Brčko and Zenica.

This order of priorities dictates Serbia’s behavior towards Bosnia. The events of the 1990s and their interpretation as a liberation war remain the main obstacle for removing the fundamental impediment to state consolidation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as the normalization of relations with Serbia.

Croatia’s Interests in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Welcoming a developed and stable Bosnia and Herzegovina as a member of the EU and NATO is one of the main interests for Croatia.

The Croatian government has invested considerable sums from the state budget into projects in Bosnia and Herzegovina. However financial support is not the only assistance that Bosnia and Herzegovina needs. Reform of the political system and proper representation of Croatian people in state institutions is even more urgent, especially in light of what Croatian Ambassador to the UN, Ivan Šimonović, stated during a Security Council meeting last year, that Željko Komšić is not a legitimate representative of the Croatians and was elected by misusing an electoral law in desperate need of reform.

In 2021, a NATO summit was convened to make decide on reforms of the Alliance by 2030. This is the summit where Croatian Minister of Foreign Affairs Gordan Grlić-Radman, who is part of the “Šeks and the City” elite, refused to attend with the Croatian president, claiming it was “beneath his dignity.” It was then that President Milanović insisted on including the Dayton Agreement and electoral reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina as a necessity to be agreed upon and implemented in the final NATO declaration, under threat that without it, he would not sign the declaration.

To the Croatian people, who are less numerous than Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and who formally do not dominate any entity, unlike Bosniaks and Serbs, there is no other option but to pursue their own policy in accordance with their national and other interests, which is only possible if they too have their secured rights and own entity – the Croatian Republic. If the Serbs can, then the Croats have the same right, and are also constitutive as an ethnic population.

It’s in the Croatian interest to supply Bosnia and Herzegovina with gas from the LNG terminal or possibly the Ionian-Adriatic gas pipeline coming from Split and continuing toward Mostar and beyond. This plan is supported by the United States and EU.

Toward EU Membership?

This year, an olive branch went out to Bosnia and Herzegovina. Many may find it odd that a country burdened with interethnic frictions and under the protectorate of the High Representative would start negotiations with the EU. Yet the serious danger of a possible armed escalation in the Balkans, influenced by Russia and China, has given rise to a new approach by the EU towards the Western Balkan countries, especially towards BiH. Although it is a gift from the EU to the most wounded country of the Western Balkans, it is nonetheless a unique opportunity for BiH to move closer to true European values, and also to gradually move away from the outdated Dayton Agreement rules and establish a fully sovereign state with three equal peoples.

The post EU Opens Membership Talks for Bosnia & Herzegovina appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

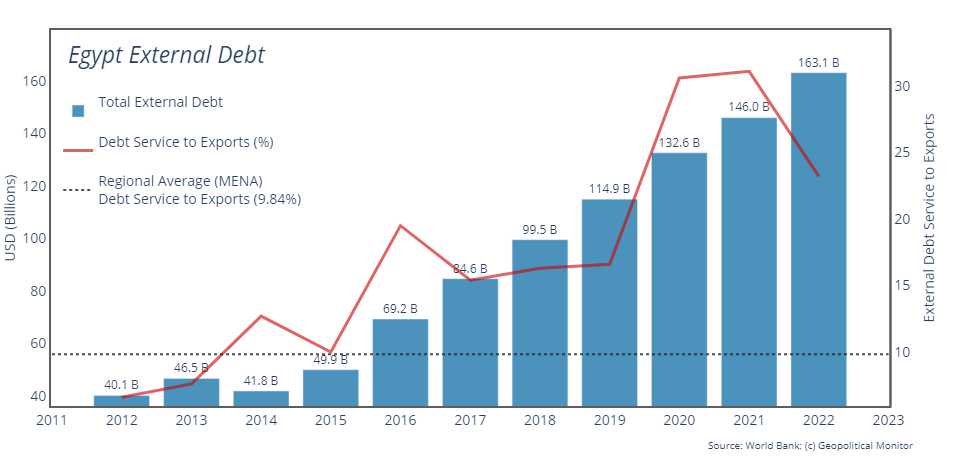

]]>The post Geopolitical Snapshot: Egypt appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

Egypt’s geopolitical importance is difficult to overstate. Strategically located at the crossroads of Africa and Asia, Egypt controls the Suez Canal, one of the world’s key maritime choke points. Each year, a significant portion of the world’s trade, including a substantial percentage of global oil shipments, passes through the canal, making its security and uninterrupted operation a prerequisite for stable global supply chains. Egypt’s geopolitical weight is further buttressed by Cairo’s historical role as a cultural and political leader in the MENA region. The country has the largest population in the Arab world at approximately 102 million, serving as a significant cultural, educational, and political hub. Its peace treaty with Israel and strategic partnerships with Western countries, especially the United States, alongside its influence in the Arab League, all cast Egypt as a pivotal player in Middle Eastern politics and peace efforts, whether in Gaza or Sudan. Consequently, the stability and policy direction of the regime directly impact regional security, counter-terrorism efforts, and the dynamics of the broader Middle East and North Africa region.

A New President for Life?

Egyptians went to the polls in 2023 amid a bleak economic outlook. The outcome of the contest was a foregone conclusion, as President Abdel Fatteh el-Sisi – the military leader who had stepped in to remove Mohamed Morsi in 2013 – took 89.6% of the vote against a withering field of competition. According to a report by Human Rights Watch, the election was marred by repression of civil society, arrests, intimidation, and the lack of any viable alternative.

The post Geopolitical Snapshot: Egypt appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

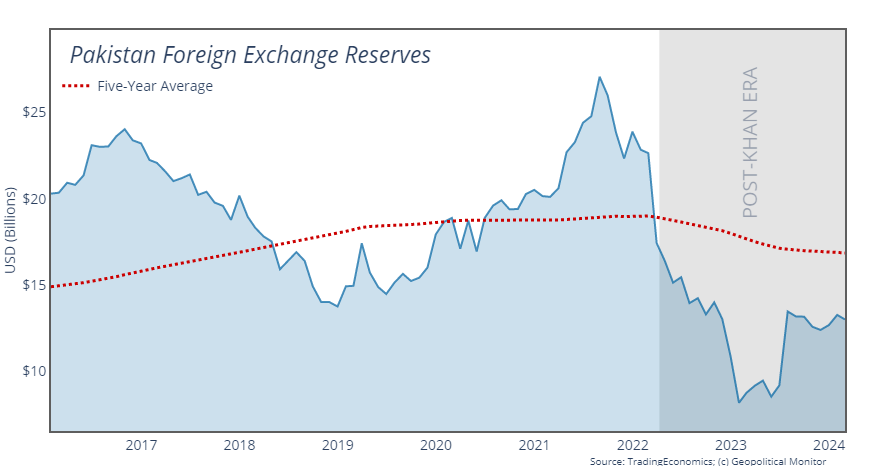

]]>The post Geopolitical Snapshot: Pakistan appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

Though it has yet to realize its economic promise, Pakistan more than makes up for this in military and diplomatic weight. The country is home to a sizable and overwhelmingly young population of over 240 million people, the fifth largest in the world; it boasts a modern and well-funded military, armed with nuclear weapons; and it borders key countries like India, China, Iran, and Afghanistan. The authorities in Islamabad, whether political or military, are also frequently involved in various internal and external conflicts, ranging from the rise, fall, and re-rise of the Taliban to cross-border Baloch separatism and India-Pakistan tensions.

The post Geopolitical Snapshot: Pakistan appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Backgrounder: Haiti’s Descent into Chaos appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The country has long been considered a failed state, where the government holds only tenuous control and is unable to deliver even the most basic services to the public. Street gangs are believed to now control over 80% of the territory in the capital city. Last week, gangs attacked two prisons, freeing at least 3,000 inmates who have now undoubtedly become participants in the street violence. Other governmental institutions, such as police stations, the presidential palace, and the interior ministry have come under attack. At present, gangs are struggling to gain control of the country’s primary seaport and airport. Prime Minister Ariel Henry, who left the country seeking international law enforcement assistance, remains unable to return.

The post Backgrounder: Haiti’s Descent into Chaos appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Backgrounder: Ethnic Armies in the Myanmar Civil War appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The ongoing conflict, characterized by its smoldering, low-intensity nature, occasionally escalates into more intense bouts of fighting before subsiding. However, since the 2021 coup, reported clashes have surged by about 67%. The ‘1027 Offensive,’ launched by the Three Brotherhood Alliance last October, appears to signal a significant shift in the conflict, with resistance forces securing substantial territorial gains and achieving numerous victories. This success has also emboldened other ethnic armed groups (EAO) to join the alliance.

Since the coup, several new EAOs and militias have emerged or reactivated, with many rallying under the National Unity Government (NUG). Comprising lawmakers elected in the 2020 election, the NUG aims to consolidate command over diverse EAOs to counter the Tatmadaw. Its military arm, the People’s Defense Forces (PDF), strives to unify all autonomous PDFs under a single command structure. While tensions persist among some EAOs, the NUG, and PDF, most disputes are set aside to facilitate collective efforts aimed at ending the military dictatorship.

Below is a comprehensive and up-to-date list of current armed groups and political parties, along with brief explanations of their backgrounds and activities. It’s important to note that the fluid nature of conflicts in certain regions means that new groups can form, existing ones may splinter, and alliances can shift over time. While this list provides an overview of the current landscape, the situation on any given day may vary.

Armed Groups and Political Organizations in Myanmar Civil War

All Burma Student Democratic Front (ABSDF): Operates along the Myanmar–Thailand border, India–Myanmar border, and China–Myanmar border. Joined the CRPH/NUG following the 2021 Myanmar coup.

Arakan Army (AA): Active in Chin State, Kachin State, Rakhine State, Shan State, Bangladesh–Myanmar border, and India–Myanmar border. Claimed troop strength of 30,000 in 2021, with over 15,000 in Chin and Rakhine State, and approximately 1,500 in Kachin and Shan State. Serves as the armed wing of the United League of Arakan and is part of the Three Brotherhood Alliance, Northern Alliance, and Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee.

Arakan Liberation Army (ALA): Operates in Kayin State and Rakhine State. Serves as the armed wing of the Arakan Liberation Party. Maintains close ties with the Karen National Union (KNU). Joined the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH)/National Unity Government (NUG) after the 2021 Myanmar coup.

Border Guard Forces: These are subdivisions of the Tatmadaw, operating under Regional Military Commands and composed of former insurgent groups from various ethnic backgrounds. Examples include the Karen Border Guard Force and the Kokang Border Guard Force.

Border Guard Police: This is a department of the Myanmar Police Force, specializing in border control, counterinsurgency operations, crowd control, and security checkpoints in border and insurgent areas.

Chinland Defense Force (CDF): Operates in Chin State, Magway Region, Sagaing Region, and along the India–Myanmar border.

Chin National Army (CNA): Active in Chin State and serving as the armed wing of the Chin National Front. It is a part of the United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC).

Chin National Defense Force: Operates in Chin State, Magway Region, Sagaing Region, and along the India–Myanmar border. It serves as the armed wing of the Chin National Organisation.

Chin National Front: A Chin nationalist political organization advocating for a federal union based on self-determination. It is a member of the National Unity Consultative Council.

Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH): An exiled Burmese legislative entity comprising of National League for Democracy lawmakers and parliamentarians displaced following the 2021 Myanmar coup d’état. With a membership drawn from both the Pyithu Hluttaw and Amyotha Hluttaw, totaling 17 individuals, the Committee aims to assume the responsibilities of Myanmar’s dissolved legislative body, the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw. Additionally, it has established a government-in-exile, the National Unity Government, collaborating with various ethnic minority insurgent factions.

Kachin Independence Army (KIA): Formed in response to Ne Win’s 1962 Burmese coup, the KIA operates in Kachin State and northern Shan State. It serves as the armed wing of the Kachin Independence Organisation and is part of the United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC). Additionally, it is a member of the Northern Alliance and the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee.

Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO): Led by Chairman N’Ban La, its armed wing is financed primarily via the cross-border trade with China in jade, timber, and gold. Additionally, funds are raised through taxes imposed by the KIA on locals.

Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA): Operates across Kayah State, Kayin State, and the Tanintharyi Region, serving as the armed wing of the Karen National Union (KNU) and a member of the United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC). It broke its ceasefire following the 2021 coup.

Karen National Union (KNU): Operates in Kayah State and Kayin State as an affiliate of the Karen National Union. After the 2021 coup, it broke its ceasefire agreement, shifting its goal from independence to establishing a federal, democratic system in Burma.

Karenni Army (KA): Operates in Kayah State, serving as the armed wing of the Karenni National Progressive Party. It is also a member of the United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC). The group resumed hostilities following the 2021 coup.

Karenni Nationalities Defense Force (KNDF): Operates in Kayah State, Shan State, Kayin State, and along the Myanmar–Thailand border; formed in response to the 2021 coup. It claims to be a unified organization comprising various Karenni youth resistance forces, totaling 22 battalions, including three based in Karenni State, two in Shan State, and several ethnic armed organizations. It includes other groups such as the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP) and aims to overthrow the junta, following the defense policy of the National Unity Government (NUG) and the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH).

Karenni National People’s Liberation Front (KNPLF): A communist and Karenni nationalist insurgent group, the KNPLF is active in Kayah State. Initially served as a government Border Guard Force, it now collaborates with various armed groups, including the Karenni Army, Karenni Nationalities Defence Force, Karen National Liberation Army, and People’s Defence Force.

Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP): A political organization based in Kayah State. In 2021, the KNPP joined the National Unity Consultative Council.

Kokang Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA): Operates in the Kokang region. It broke its ceasefire agreement following the coup and resumed fighting against the government. The MNDAA participated in Operation 1027 alongside its allies, the Arakan Army and Ta’ang National Liberation Army. On January 5, 2024, the MNDAA seized full control of Laukkai, the capital of Kokang, after defeating Tatmadaw forces.

Mon National Liberation Army (MNLA): Operates in Mon State and the Tanintharyi Region, serving as the armed wing of the New Mon State Party. It entered into a ceasefire agreement in 2018.

Mon National Liberation Army (Anti-Military Dictatorship) (MNLA A-MD): Formed in 2024 after splitting from the MNLA. It disregarded the ceasefire and joined the anti-junta forces.

Myanmar Army, or ‘Tatmadaw’: Along with its affiliated political entity, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), and the ruling junta known as The State Administration Council (SAC), the Tatmadaw emerged as a combatant following the 2021 coup, led by Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services Min Aung Hlaing. The National Defence and Security Council declared a state of emergency, granting the commander-in-chief absolute legislative, executive, and judicial authority as per the constitution. Min Aung Hlaing delegated his legislative powers to the SAC, which he leads, establishing a provisional government, with Min Aung Hlaing also serving as the prime minister of Myanmar.

Myanmar Air Force: Equipped with jets and attack helicopters from Russia and the People’s Republic of China, the Air Force regularly violates Thai airspace and has been reported to drop bombs on civilians near the border.

Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA): Operates in Shan State (Kokang) after splitting from the Communist Party of Burma. It serves as the armed wing of the Myanmar National Truth and Justice Party and is part of the Three Brotherhood Alliance, the Northern Alliance, and the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee.

National League for Democracy (NLD): The pro-democracy political party led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, which emerged victorious in both the 2015 and 2020 elections. Although the NLD does not have a direct militia, it garners support from various resistance armies. The junta dissolved the NLD, purportedly due to its failure to renew its registration as a political party.

National Unity Government (NUG): Established in 2021 by Min Ko Naing, a prominent pro-democracy figure, with a significant representation of members from ethnic minority communities. Min Ko Naing declared that ousted leaders Aung San Suu Kyi and Win Myint would retain their positions within the NUG and urged the international community to recognize their government instead of the ruling junta. The European Union has acknowledged the NUG as the government-in-exile, and the NUG has appointed representatives in the USA and UK. The People’s Defense Force (PDF) serves as its armed wing, and the NUG has instituted People’s Administration Teams (Pa Ah Pha) to oversee areas under its control.

Northern Alliance: Comprising of the Arakan Army (AA), the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), the Northern Alliance is active in Shan State. The alliance is also a member of the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC).

Pa-O National Army (PNA): Operates in Shan State and allied with the Tatmadaw. It serves as the armed wing of the Pa-O National Organisation and is responsible for safeguarding the PNO-administered Pa-O Self-Administered Zone, comprising of Hopong, Hsi Hseng, and Pinlaung townships in southern Shan State. Since the 2021 coup, the PNA has actively recruited for the Tatmadaw.

Pa-O National Liberation Army (PNLA): Aligned with the resistance against the Tatmadaw and has pledged support to the National Unity Government (NUG) in defeating the junta and establishing a federal system. In 2024, it formally revoked its ceasefire and began coordinating with local People’s Defense Forces (PDF) and the Karenni Nationalities Defense Force (KNDF), launching attacks against the junta and its aligned forces.

Pa-O National Organisation (PNO): Maintains close ties with the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP).

People’s Defense Forces (PDF): Serves as the military wing of the National Unity Government (NUG) and comprises of roughly 65,000 troops. Composed of resistance groups and anti-junta ethnic militias, the PDF bears ethnic or regional names such as Chinland Defence Force, People’s Defence Force (Kalay), and Karenni People’s Defence Force.

People’s Liberation Army (PLA): Affiliated with the Communist Party of Burma (CPB), the PLA was reactivated on March 15, 2021, when communist fighters crossed from China into Kachin State. The Kachin Independence Army (KIA) provided them with weapons to combat the ruling junta. Additionally, the PLA operates within the Tanintharyi Region, situated in the southernmost part of Myanmar, extending along the upper Malay peninsula to the Kra Isthmus. It shares borders with the Andaman Sea to the west, Thailand beyond the Tenasserim Hills to the east, and the Mon State to the north. Collaborating with the People’s Defense Forces (PDF), the PLA asserts to have approximately 1,000 active troops as of December 2023.

Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO): Operates in Rakhine State and along the Bangladesh–Myanmar border. It was reactivated since the coup.

Shan State Army North (SSA-N): Operates in Shan State and serves as the armed wing of the Shan State Progress Party (SSPP). Allied with the Tatmadaw, it declared a truce with the Shan State Army – South on November 30, 2023, claiming to be planning to unite the two armies in the future.

Shan State Army – South (SSA-S): Operates in Shan State along the Myanmar–Thailand border and stands as one of the largest insurgent groups in Myanmar. Serving as the armed wing of the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) and a part of the Shan State Congress, it maintains alliances or ceasefire arrangements with the Tatmadaw. Currently not aligned with the resistance, it is led by Lieutenant General Yawd Serk and is headquartered in Loi Tai Leng. Its political arm is the Restoration Council of Shan State. On February 19, 2024, the RCSS implemented mandatory conscription for all citizens aged 18–45 residing in its territory, obliging them to serve a minimum of six years in the SSA-S, with severe penalties for refusal.

Shanni Nationalities Army (SNA): Operates in Kachin State and aligns itself with the Shan State Army – South and the Tatmadaw.

State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC): Later rebranded as the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), emerged as a military junta following the pro-democracy People Power Uprising of 1988, also known as the 8888 uprising.

Student Armed Force (SAF): Established after the coup by members of Yangon-based University Student Unions. They received basic military training from the Arakan Army. Former actress Honey Nway Oo currently holds a senior officer position within the SAF.

Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA): Operates in Shan State with an estimated troop strength of 10,000 to 15,000. It is a member of the United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC), the Three Brotherhood Alliance, the Northern Alliance, and the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee. The TNLA also governs the Pa Laung Self-Administered Zone.

Three Brotherhood Alliance: Consists of the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and the Arakan Army (AA). It is an anti-junta alliance operating primarily in Rakhine State and northern Shan State. The alliance spearheaded Operation 1027, a successful offensive against the junta in northern Shan State, marking a significant turning point in the conflict.

United Wa State Army (UWSA): Operates in Shan State and is regarded as Myanmar’s most powerful and well-armed army, boasting around 30,000 troops equipped with modern weapons. It serves as the armed wing of the United Wa State Party (UWSP) and is a member of the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee. The UWSA governs the Wa Self-Administered Division (Wa State) and maintains a de facto ceasefire with the government. It has frequently allied with the Tatmadaw to combat Shan nationalist militia groups, including the Shan State Army – South. Unlike other armed groups, the UWSA is not pursuing independence or secession. Instead, it engages in extensive business and trade with China and earns revenue from drug and weapon production. Notably, the UWSA has acquired surface-to-air missiles from China to counter the Tatmadaw’s air superiority, a critical asset for insurgent groups.

United Wa State Party: The governing party of Wa State, led by Bao Youxiang (known as Tax Log Pang in Wa, Dax Lōug Bang in Chinese Wa, and Pau Yu Chang in Burmese). Bao Youxiang serves as the President of the Wa State People’s Government, the General Secretary of the United Wa State Party, and the Commander-in-Chief of the United Wa State Army.

The post Backgrounder: Ethnic Armies in the Myanmar Civil War appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>