The post CBO Hints at Future US Sovereign Debt Crisis appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

Summary

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) – the nominally non-partisan and impartial ‘umpire’ of US fiscal policy – released its latest long-term projections in March. The numbers convey what is essentially an open secret in Washington, that US finances are on a wholly unsustainable track. Yet the extent of the fiscal pressures, which stem from rapid growth in interest payments and mandatory spending, and the immediacy with which they will begin to be felt make for some sobering reading. Simply put, the problem of tomorrow is becoming the crisis of today, and this will resonate in onerous fiscal constraints in US politics in the coming years, with variables like interest rates and economic growth amplifying or easing the pressure. At best, the nature of US politics will change; at worst, a crisis of faith will shake the foundations of global finance, fracturing the pillars of the post-Cold War global order.

Background

US Interest Payments Set to Spike

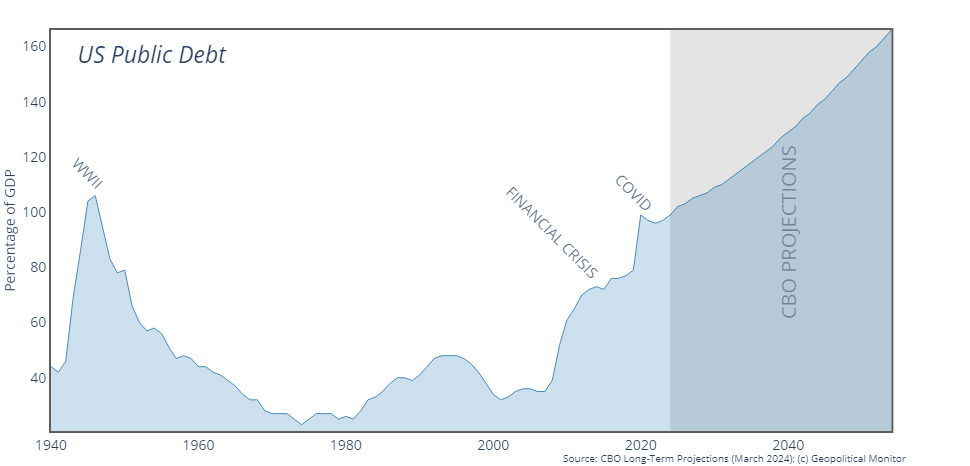

What a difference 15 years can make. In 2008, US public debt stood at 39% of GDP; now that number is hovering around 100%, buoyed by the combined fiscal pressures of the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic. The CBO’s long-term estimates from 2024 onward point the way to ever-greater heights, with the debt projected to hit 166% of GDP by 2054. Debt growth will be fueled by ballooning overall deficits, despite primary deficits (pre-interest spending) expected to remain either unchanged or smaller relative to GDP over time. In other words, deficits are on a destabilizing track regardless of how the discretionary budget is handled, driven by a ‘locked-in’ expansion in mandatory spending and debt servicing costs.

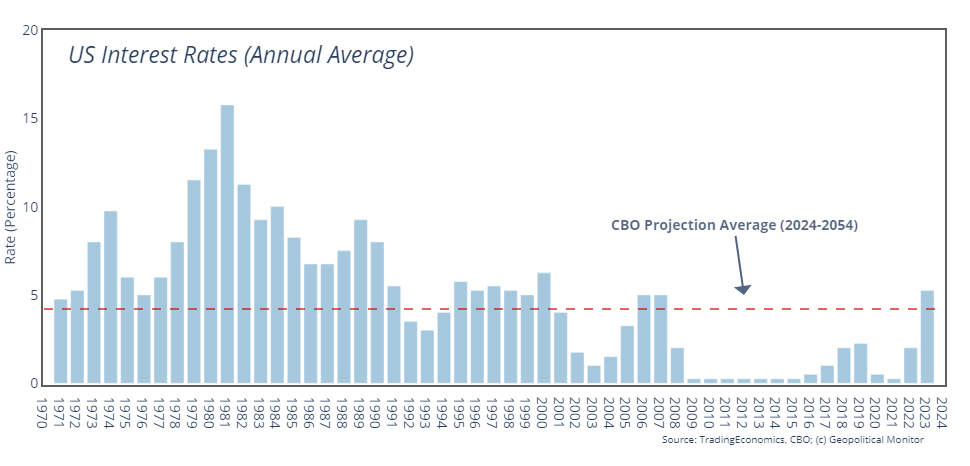

The included charts illustrate that the US government has been spending beyond its means and, barring a major course-correction, will soon face unprecedented fiscal pressure from ballooning interest payments. Such payments have already doubled in just a few years, jumping from 1.5% of GDP in 2021 to 3.1% in 2024. In absolute terms, going by the CBO’s 2024 GDP numbers, this translates into an additional $426 billion in annual outlays. The current fiscal year thus marks a turning point where the cost of debt servicing actually might exceed the entire defense budget of the United States. And it only gets worse from here: by 2034, the US government will be paying $1.6 trillion annually in interest, and interest payments will account for 64% of the deficit. And by 2050, annual interest payments will reach $4.2 trillion according to the CBO’s economic baselines.

This dire fiscal outlook ensures that future governments will be forced to borrow to cover previous debt obligations. Not only is this economically wasteful since no new productive capacity is being created, but it involves considerable fiscal risk, especially given the extent of the public debt. The overriding takeaway is that US fiscal stability will become inexorably tied to the functioning and goodwill of debt markets. Interest rate fluctuations in particular will reverberate in hundreds of billions worth of payments added or subtracted.

The post CBO Hints at Future US Sovereign Debt Crisis appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Japan’s Diplomatic Bluebook Paints China as Central Villain appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The changes are also representative of the technological advancements that have altered the security dynamic in the region, as Tokyo worries about China’s dramatic increases in military spending, which the U.S. recently warned could exceed more than $700 billion. This was parallel to a concern raised by Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi back in March. The fog in which Beijing operates also comes from a buildup in the East and South China Seas, which has drawn the ire of Defense Minister Minoru Kihara. Informationization has long been a priority of China, which has aimed to open a new area of modern warfare through multiple channels of communication-based infrastructure.

Confronting China in the security realm is a monumental challenge, as Japan is still largely dependent on the United States and security ties to Indo-Pacific partners like India and EU Member States are still in the early stages. Attempts at more assertive bilateral communication, such as through the Japan-China Security Dialogue and its attempt at a communications hotline with Beijing last year, have mostly been fruitless affairs. Thus, the third chapter of the new Bluebook is a formal and public diplomatic explanation of its alliance and defense strategies that are squarely aimed at China, as well as lingering security threats from North Korea and Russia. For keen observers of Japan’s defense policy, this is not at all surprising and has been a part of Japan’s security and defense reorientation for several years.

With China now squarely in the sights of Japan, also evident in the 2023 Bluebook is a strong indicator that Tokyo’s foreign policy environment will be volatile at best, with policy aimed at responding to PLA coercion through a stronger promotion of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific plan that aims to broaden regional cooperation. This cooperation will play out in the realm of maritime security, intending to mitigate any damage caused by China’s “economic coercion,” which was also a key theme of the 2023 G7 Summit in Osaka.

As is typical in this long-running publication, Japan presents itself in the most positive light, focusing on an open diplomacy rich with evidence of its soft power and status projection, with cherry-picked examples from its engagement in Africa through TICAD, Security Council leadership and reform efforts, and nuclear disarmament objectives. What’s missing is the stark contrast between Tokyo and Beijing on the international stage, where China’s lead on the African continent is miles ahead, both in terms of extractive industries, rare earth minerals, infrastructure, and the size of its diplomatic presence. Beijing’s soft power also extends into complex relationships with line ministries and civil society, where the funding of hospitals and other critical development provide evidence to the scale of Japan’s challenge.

But closer to home, the pillars of Japan’s FOIP plan offer clues on how it can go toe to toe with Beijing, balancing the combative rhetoric with real-world results. For example under Pillar 1, “Principles for Peace and Rules for Prosperity,” the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) offers Japan a chance to engage with ASEAN partners at the ministerial-level, particularly in areas where each share vulnerabilities that were exacerbated by COVID-19 and continued Chinese aggression in the all-important Strait of Malacca. Second, in its own backyard and in the tense South China Sea, Japan’s emphasis on strengthening the rule of law through a variety of institutional mechanisms as well as flexing its diplomatic credentials and well-earned reputation in Southeast Asia via technical assistance and training to critical partners like Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Indonesia.

Clearly, the Chinese reaction was predictably negative and it also provoked nationalist sentiments in South Korea over its claims to “Dokdo” or Takeshima, but this is par for the course with a less than surprising reorientation of Japan’s security posture.

As I said, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Mark S. Cogan is an Associate Professor of Peace and Conflict Studies at Kansai Gaidai University in Osaka, Japan. He is a former communications specialist with the United Nations in Southeast Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.

The post Japan’s Diplomatic Bluebook Paints China as Central Villain appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Strategic Use of Migration: The View from Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

Emigration as Economic Alleviation

Some countries actively encourage emigration as a strategy for development. Migrant laborers send back a portion of their earnings – remittances – which can have multiplier effects on the home economy.

For many countries, remittances make up a larger portion of gross domestic product (GDP) than foreign direct investment (FDI). The World Bank’s data shows that Nicaragua’s 2022 GDP was over 20% remittances and just over 8% FDI. In 2023, remittances to Nicaragua were nearly 50% higher than the year before, standing at $4.24 billion, an estimated 28% of GDP.

Venezuela, on the other hand, has consistently received fewer remittances and very little FDI between 2000-2022 (both remaining largely below 2% of GDP according to World Bank data), though the Inter-American Dialogue estimates that remittances reached 5% of GDP in 2023. Interesting hypotheses can be considered to explain this behavior, such as the migration of entire family households, and/or a lack of confidence in the country’s future as a destination for personal and family investment.

While there is not sufficient data about the amount of remittances and their weight in Cuba’s economy, indirect evidence suggests that the chronic economic crisis was aggravated further after an estimated decrease of 3.31% in remittances since 2022, despite an amendment to the limit approved by the US government. Thus, in Cuba, migration appears to be an asset for political stability rather than a path for economic alleviation, given other structural factors that exert a more significant effect on the national economy.

However, the inherent risk is that overreliance on remittances does not constitute a sustainable economic development model. Remittances present an “easy” lifeline for governments, which may disincentivize diversification and state-sponsored investment in the economy. As Manuel Orozco observes in Nicaragua, remittances are unsustainably shouldering the responsibility of supporting private investment, providing access to credit, and reducing debt. Nicaragua taxes the added income from remittances, which supports the regime. Nicaragua is not reinvesting such taxes in the country.

Overreliance on remittances can also increase the vulnerability of governments antagonistic to the United States. For example, as Nicaragua increasingly relies on remittances, future policy pressure from Washington may significantly tamper growth and increase the prospect for new civil unrest crises. This is also echoed in previous debates in the U.S. about using the Patriot Act antiterrorism law to cut off remittances to hostile governments.

Emigration as a Political Stabilizer

Allowing or encouraging emigration can politically stabilize countries with high labor surplus or political dissatisfaction. Emigration reduces unemployment, which can reduce economic grievances, known as the “safety valve” effect. Relatedly, the emigration of political dissidents or economically dissatisfied citizens leaves only the more satisfied, passively dissatisfied, and regime-supporting citizens in the country, which translates to reduced risks of political violence and protest.

This safety valve effect was well understood by Fidel Castro. Over his decades-long rule, he repeatedly allowed political dissidents or economically disaffected Cubans to emigrate to the United States, with the most salient example being the 1980 Mariel Boatlift. Cuba continued to use the emigration safety valve while the US’ “wet foot, dry foot” policy was in place.

In Cuba, after the mass protests of July 11, 2021 the regime developed major legal disincentives for future protests. The penal code approved in September 2022 included more severe penalties for individuals who commit acts against the socialist constitutional order. Similarly, Nicaragua and Venezuela have approved legislation such as Nicaragua’s 977, 1042, and 1055 laws, and Venezuela’s laws against organized crime and financing of terrorism, and against hate, for peaceful coexistence and tolerance. These new pieces of legislation along with high discretionary application deter many from further engaging in domestic political life and incentivize greater emigration.

Emigration, however, also creates chances for the potential formation of external diaspora opposition or internal opposition groups supported by diasporas. For example, diasporas can “remit” democratic values and opposition back home. In Venezuela, the diaspora has represented opportunities for increased engagement from the opposition with international organizations, foreign governments, and even the formation of a contending parallel government (as in the appointment of Juan Guaidó as interim president and a series of congress members in exile). For this reason, some diasporas have faced measures to restrict the entry of funding into the home country. For example, Nicaragua has approved a foreign agent law, increased monitoring and restriction of remittances, awards from abroad, and cryptocurrency transactions.

Emigration for Geopolitical Leverage

Internationally, countries can leverage emigration crises to destabilize or extract concessions from neighboring countries. This is a form of “reputational blackmail” often directed at more liberal destination countries, which highlights liberal countries’ inconsistent commitments to championing life and liberty while simultaneously attempting to keep asylum seekers out.

The central historical example of this strategy is Cuba’s 1980 Mariel Boatlift, when Castro sent thousands of “socially undesirable” migrants to the U.S., turning up the political heat on President Jimmy Carter in the hope of reducing criticism of the Castro regime.

Migration, not only from but also through Nicaragua, has allegedly been used as an attempt by the Ortega-Murillo regime to exert geopolitical leverage by increasing the weight of migration on the U.S., presumably in exchange for sanction relief. Charter and scheduled flights from several migration origins have been reported to arrive in Managua as part of global migrant trafficking networks, as Nicaragua represents an attractive “shortcut” to alternatives like the Darien Gap. Flights with Cuban, Haitian, Indian, Moroccan, and Senegalese migrants among several others, have been reported to arrive regularly in Managua, from where migrants travel by land to the U.S.

Similarly, in 2024, facing the prospect of US sanctions on Venezuelan oil, Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodríguez told the United States: “If they carry out the false step of intensifying economic aggression against Venezuela, at the request of extremist lackeys in the country, from Feb. 13 the repatriation flights of Venezuelan migrants will be immediately revoked.” The logic behind these strategies is to threaten Washington with more migrants (or to be stuck with migrants presently on US territory) to deter the US government from levying sanctions.

However, this strategy can invite retaliation. For example, Washington imposed sanctions on “flight operators facilitating irregular migration” from Nicaragua in November 2023, February 2024, and March 2024, which have been also addressed by the governments of Haiti and Belize.

Policy Recommendations for the United States

The diversity of strategic interests related to migration in the surveyed Latin American countries highlights the necessity of tailor-made policies rather than one-size approaches to migration from Latin America. The US government should reward more cooperation with more economic support.

In terms of carrots, along with developmental aid, the United States should implement incentives for governments in the region to cooperate with the enforcement of regular migration, thus creating a buffer zone that distributes the weight of temporary migrant assistance across several countries. This assistance is something Washington should be directly involved in.

The U.S. should also consider the implementation of incentives for local companies to nearshore business processes to disincentivize economic emigration. This is the underlying motivation for the 2021 “Root Causes Strategy,” which the U.S. should continue and also expand to include the countries discussed above.

To address political emigration, the United States has often promoted democracy and good governance. While the long-term impact of such policies may reduce emigration by political dissidents, democratizing pressures may antagonize autocratic governments, which may then weaponize migration against the U.S. An alternative is to build countries’ migration management capacity, but this effectively strengthens autocratic governments’ repressive apparatus. Short-term emigration may decline at the cost of greater future political emigration.

In addressing both root causes, the United States could expand its avenues for “regular” migration, while investing in its processing capacity to ensure its own security. Increased opportunities for safe and regular migration would disincentivize irregular crossings, while simultaneously allowing the U.S. to vet incoming migrants. Allowing vetted migrants would help the U.S. address its own labor shortages and help Latin American countries reduce unemployment and increase remittances.

In terms of sticks, Washington can use economic and selective sanctions against countries being actively uncooperative on (i.e. weaponizing) migration. This has been the response to Nicaragua. The U.S. should mitigate any expected backlash by increasing regional multilateral efforts at migration management.

Overall, the United States must match its policies to the emigration countries’ motivations, crafting a holistic approach that acknowledges the interrelated impacts of diplomatic, security, economic, and migration management policies.

Giacomo Mattei is a PhD student at The George Washington University studying migration geopolitics and security.

Luis Campos is chief analyst and editor for the Americas at Horizon Intelligence and author of Puentes y Cercos: La Geopolítica de la Integración Centroamericana published by Glasstree Academic Publishing.

The post Strategic Use of Migration: The View from Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Embracing European History and Mortality in Eastern Poland appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>This part of the world, for better or for worse, remains a vanguard and a bulwark of history. It is the dividing line between dignity and barbarism, a Europe whole and free or one that remains captive to the revanchist aims of its much larger neighbor. It is not a borderland at the edge of Europe but increasingly the capital of, and in Ukraine, the future of, a Europe that exists in its truest and most complicated form. It is not a Europe trying to escape from history but one that brings forth constant reminders of a darker past. In a recent speech at the Sorbonne in Paris, President Emmanuel Macron was right to echo this sentiment by saying ‘our Europe is mortal.’ After two years of conflict in Ukraine, Macron is starting to speak more for Europe, notably because he has listened to and has gained the trust of NATO’s Central and Eastern European member states. An ardent Europhile seeking to break free from history would never dare to preach about Europe’s mortality. However, with the help of Poland, Czechia, and others, the cautious winds of history have started to blow further west, bringing a strategic clarity and foresight to leaders like Macron that is to the benefit of all of Europe.

Traveling through eastern Poland recalls the importance of staying principled and strong in the face of aggression, of not succumbing to half-measures but of going all in for the sake of history. Ukraine feels very close from Lublin, Zamość and Rzeszów, and the psychological impact of NATO as a security guarantor provides a palpable sense of calm and reassurance. Security can be measured in many ways, from the amount of military hardware a state possesses, to where that hardware is positioned, and the percent of GDP a state spends on defense, all of which make Poland one of NATO’s most secure member states. However, security’s most powerful measurement is psychological, knowing that you are safer because of pledges and commitments made amongst allies who will come to your aid in the event of an attack. Poles living in close proximity to the Ukrainian border know this, as does President Putin, signifying a degree of fraternal order and protection that remains non-existent at Ukraine’s opposite border in the east.

Supposed promises made to Gorbachev about the enlargement of NATO in 1990 become irrelevant over 30 years later when the soil is that much more secure and the process of obtaining that security is a result of the wishes of a sovereign people. The smallest Polish villages in the Lublin and Subcarpathian provinces may not be known in all the capitals of NATO, but they have been deemed worth defending. In a region where borders and thus nationality and identity used to constantly change at the barrel of a gun in the 19th and early 20th centuries, there is a comfort in knowing that while no border is inviolable, its legitimacy and defense has become institutionalized. This is the result of many years of painstaking European integration that will one day hopefully extend all the way to Ukraine’s eastern border with its invader and occupier.

As the world increasingly turns its attention to the Indo-Pacific, Africa, and other centers of growth in the 21st century, it can be tempting to view Europe as a relic of the past. However, eastern Poland shatters that narrative, as it is where the questions surrounding Europe’s mortality and the West’s future as a geostrategic actor in a world of enhanced competition and multipolarity are on full display. So long as there is war in Europe, there is increased mortality in Europe as the demons of the past threaten to raise their heads. Europe’s mortality is a direct consequence of its fractious history, just as traveling in eastern Poland serves as a reminder of the thin line between progress and barbarism, of being oppressed versus being the oppressor, and of the dangers of appeasement and complacency in the face of strife. The fields of Lublin and Subcarpathia reveal that nothing in our present moment is black and white, oppression does not discriminate, and there is no fixed power dynamic to provide a sense of moral clarity in times of turbulence.

This Europe is raw and close to the ground, comprised of flawed individuals, imperfect choices, and an internal battle to do what is right versus what is politically expedient. It is fragile yet sacrosanct, rooted in a rich culture, and yet ever susceptible to the act of wandering as great writers such as Joseph Roth and Stefan Zweig have famously chronicled. At a moment’s notice, culture can be erased and survival, that delicate dance with mortality at both the individual and the nation-state level, can guide all actions. To traverse eastern Poland is to bear witness to a tragic history but also a hopeful future should the states of Europe and her allies choose to make it so. Likewise, to declare Europe mortal is to summon its life and the lives of those cut short on its soil in order to help guide the next generation to more prosperous lands.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.

The post Embracing European History and Mortality in Eastern Poland appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post The EU in the Middle East: Challenges and Opportunities appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>

EU Policy in the Middle East

The EU has pursued two main strategies toward the Middle East region in the past two decades: the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP) and the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (EMP). These strategies have aimed to prevent the spread of security crises in the Union’s neighboring countries by promoting European norms, such as liberal democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. However, these strategies have proven to be ineffective and insufficient in dealing with fast-changing and dynamic developments in the region. The ENP and the EMP have failed to address the root causes of the problems and conflicts in the region, such as the lack of political and economic reforms, the marginalization and oppression of people, the interference of external actors, and the unresolved issue of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Recent regional events, such as the Arab Spring and the emergence of new power structures and transnational actors, have shown the limitations and inefficiencies of these strategies. They have also highlighted the need for the European Union to review and redefine its role in the international system, especially in the Middle East region.

The EU acknowledged this need in its global strategy document of 2016, where it stated that internal and external security are interlinked and that the current challenges and threats, such as terrorism and violence, in the Middle East and North Africa region are a common opportunity for EU countries to build a stronger Europe based on interests and principles. The EU also declared its intention to enhance its security and defense policy by developing more military capabilities and increasing its cooperation with NATO and other partners. Finally, Brussels expressed its commitment to support the political and economic transitions in the region by providing more financial and technical assistance, fostering dialogue and cooperation, and promoting regional integration and stability.

EU Challenges in the Middle East

However, the EU faces three barriers to playing an active and effective role in the Middle East. Firstly, there is a lack of a coherent and comprehensive approach toward the region at the Union level. This stems from the divergent interests and perspectives of the major European countries, which make it hard to reach a common policy in dealing with the complex and diverse issues and actors in the region. This problem has led to the independent policies of large and powerful European countries, such as France and Germany, who pursue bilateral interactions with regional actors to gain influence and geostrategic position. Another factor that limits the EU’s role is the economic crisis, which has reduced the financial capacity of the Union to manage and respond to the needs of this crisis-stricken region. The EU’s structural weakness, the lack of a judicial mechanism to enforce its decisions and resolutions, and its insufficient foreign policy levers are other factors that undermine the Union’s decision-making capacity.

Secondly, the Middle East has diverse and complex political structures, problems, crises, and actors. The governments in the region are not mainly based on the will and vote of the people, but rather on various forms of authoritarianism, sectarianism, nationalism, and tribalism. The region also faces various types of crises, such as civil wars, ethnic conflicts, humanitarian disasters, terrorism, and extremism. The actors in the region are not only states but also non-state actors, such as militias, rebel groups, religious movements, and regional powers. These factors make it difficult for the Union to adopt a fixed and specific policy for the region, as it has to deal with each case separately and independently.

Lastly, trans-Atlantic issues have also hindered the EU’s active and effective role in the Middle East, as the United States and Israel have often opposed the EU’s independent role, instead preferring that the EU play a complementary role within the framework of their policies. The United States and Israel have different interests and perspectives from the EU on various issues in the region, such as the Iranian nuclear program, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Syrian crisis, and the role of regional powers.

EU Opportunities in the Middle East

Despite these challenges, the EU also has some opportunities to play a positive and constructive role in the Middle East, by using its soft power and diplomatic tools, as well as its economic and humanitarian aid. The EU can leverage its reputation and credibility as a neutral and honest broker, as well as its experience and expertise in conflict resolution and peacebuilding, to mediate and facilitate dialogue and cooperation among the conflicting parties in the region. The EU can also support the political and economic reforms and transitions in the region by providing more incentives and conditionality, as well as more flexibility and differentiation, to the countries that are willing and able to implement the European norms and values. The EU can also promote regional integration and stability by supporting the existing regional organizations and initiatives, such as the Arab League and the Arab Peace Initiative, and by creating new platforms and mechanisms for dialogue and cooperation, such as the Union for the Mediterranean and the 5+5 Dialogue.

The EU can also cooperate and coordinate with other international and regional actors, such as the United States, Russia, China, Turkey, and Iran, to address the common challenges and threats in the region, such as the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, global terrorism, climate change, and migration. Finally, the EU can use its trade and energy relations with the region, as well as its development and humanitarian assistance, to foster economic and social development, reduce poverty and inequality, and improve the living conditions and human rights of the people in the region.

The post The EU in the Middle East: Challenges and Opportunities appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post The Kadyrov Dynasty Set to Endure in Chechnya appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>However, rumors concerning Kadyrov’s health have been a consistent feature of late. Earlier on, the rumors claimed Kadyrov had suffered from kidney failure. More recently, reports suggest that Kadyrov was suffering from pancreatic necrosis in 2019, and his condition has worsened in the meantime. While Kadyrov released a clip of him exercising to divert public attention, speculation concerning his health is still rife.

Yet whether Kadyrov is healthy or not, one thing is sure: Chechnya will remain stable, even in a post-Ramzan Kadyrov situation. The stronger-than-expectation control of Moscow, Kadyrov’s dynastic strength, and the lack of sufficient opposition inside Chechnya will combine to sustain the status quo.

Moscow’s Iron Grip on Chechnya

Many have argued that the Moscow government has already lost de facto control over Chechnya, as Kadyrov’s force is independent from Moscow’s command. Moscow also handed over control of the Chechen oil company to the Chechen government, granting a strong boost in direct financial resources. Furthermore, Chechnya’s history of friction with Russia and Kadyrov’s blunt criticisms surrounding the Ukraine war could be interpreted as potential drift away from Moscow.

However, in reality, Moscow retains tight control over Chechnya in other ways. Economically and politically, the current regional authority can only survive with Moscow’s continued support.

Moscow indeed granted a degree of economic independence to the Chechen government. Yet, Chechnya relies on Russian transfer payment to survive. Russian subsidies comprised 87% of the Chechen annual budget, and these payments survived the federal funding cut of 2017. Even Kadyrov has recognized that Chechnya would not survive without Moscow’s fiscal support, as Moscow provides around $3.8 billion dollars a year to the Grozny government. Chechnya continues to suffer from extremely high unemployment while building massive mosques and modern business districts. Only Moscow’s cash can sustain this deformed economy.

The Kremlin also keeps its eye on the political arena in Chechnya, and Putin has indicated a willingness to tip the scales on the next Chechen leader. This could end up being someone other than the heirs of the Kadyrov dynasty, whom Russian propaganda has consistently promoted. Moscow has recently appointed Apti Alaudinov, Kadyrov’s right-hand man, as director of military-political work at the Russian Ministry of Defense. The promotion generated some speculation about Alaudinov’s succession to the Chechen government. The news also reinforces the fact that Moscow has the ability to install any Chechen leader it wishes, further reinforcing Moscow’s iron grip over the region.

The Kadyrov Dynasty

Kadyrov and his relatives have obtained great political trust in Moscow. Over the past 25 years, Kadyrov managed to build a dynastic rule in Chechnya, and one way or another this dynasty will play a key role in maintaining Chechnya’s stability after Ramzan Kadyrov.

Some reports indicated that more than half of the critical positions inside the Chechen government are held by relatives of Ramzan Kadyrov or members of his village. Besides politics and the military, the Kadyrov family also makes massive profits in Chechnya. For example, in 2015 it was claimed that Kadyrov and his family imposed an unofficial tax upon Chechens. The French dairy company Danone also has plans to sell its Russia operations to a management team directly linked with the Kadyrov family.

Meanwhile, Kadyrov still shares the same interests as the Moscow government. As previously mentioned, Moscow has the ability to control Chechnya in various ways. Kadyrov’s family has gained massive economic and political privileges under the current system. It’s obvious that Kadyrovs are thriving under Moscow’s goodwill; thus, there is no practical reason for the family to challenge Moscow’s authority.

Ramzan Kadyrov is also preparing for the next generation to take over. Kadyrov’s elder son, Akhmad Kadyrov, has met with Putin. Although it was an unofficial meeting, the move seems a clear indication that Kadyrov intends to secure his son’s position in future Chechen politics. Meanwhile, other close relatives control key positions in the Chechen government. Kadyrov’s son, Adam, heads the security department, and his daughter, Aisha, serves as the deputy prime minister of Chechnya. The next generation is now already playing a role in Chechen politics.

The Lack of Credible Opposition

Practically speaking, there is no real opposition that’s able to challenge Kadyrov. Political opponents in Chechnya are very divided over ideological differences. From liberals to extreme Islamists, there’s no common ground to work together, allowing the Chechen government to divide and conquer.

On top of this, the opposition movement has shrunk significantly. The Chechen and Moscow governments have cracked down on the region’s armed resistance activities. Some groups, like the Caucasus Emirate, have stopped their activities entirely. Similar to the remnants of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, the other groups are more active outside of Chechnya and Russia. Even in a post-Kadyrov world, these groups lack the means and resources to become involved in Chechnya.

Meanwhile, the violent nature of the Chechen regime has made dissidents either hide their presence or seek refuge outside of Chechnya. A Chechen opposition YouTuber living in Stockholm has had to fake his death to avoid assassination attempts. Meanwhile, the Grozny government also targets the family members of Chechnya activists. Even recently, Kadyrov called for blood vengeance against the relatives of wanted fugitives.

Looking Forward

Indeed, Chechnya has shown a tendency toward independence throughout the years. The region has experienced historical frictions with the Russian government; Kadyrov’s Army and its expansion challenged Moscow’s military control; and economic independence creates drift in the Moscow-Grozny relationship.

Yet one thing remains for sure: even if Kadyrov is no more, his family and right-hand men will still play essential roles in Chechen politics. The autonomous republic will not break away from Russia. Moscow remains in strong control of the region, and Chechnya lacks any opposition that can truly threaten the status of the Kadyrov dynasty.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.

The post The Kadyrov Dynasty Set to Endure in Chechnya appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Backgrounder: State Players in Middle East Geopolitics appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>Arguably, the United States and Iran could be considered the most significant players in proxy wars in the Middle East. Iran backs some of the more prominent proxies, namely Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis. These three groups are effectively shaping the trajectory of Middle East diplomatic and security dynamics. In every conflict where Iranian-backed proxies are active, US-backed proxies are fighting them. The recent Hamas attack on Israel has escalated tensions, prompting countries to take sides. The taking of sides also results in the deployment of proxies. And while Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and other nations support proxies in various conflicts, Russia, with its much broader scope of policy interests, is arguably the third most prominent sponsor in the region.

The post Backgrounder: State Players in Middle East Geopolitics appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Is Haiti’s New Transitional Government a Game Changer? appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>For one thing, it is a nod to the Caribbean Community (CARICOM)—among others—which pulled out all the stops to come to Haiti’s aid in this precarious moment.

For another, it provides a much-needed sign of better times to come. Haitians residing in-country have endured years of political instability and hellish lived conditions, a combination of factors which weigh heavily on their everyday milieu.

This reality simultaneously took its toll on democracy rooting itself, just as much as the thin stature of democracy therein has had a bearing on the milieu in question.

On the back of a political history of Duvalier era dictatorship, then, the transition to democracy in Haiti has been fragile. It hit a major stumbling block in 2019, when constitutionally due general elections were called off. Two years later, as Haitian civil society had feared all along, the prospects for the exercise of the franchise by Haitian voters went from bad to worse.

Following the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021, with Prime Minister Ariel Henry taking up the reins of power thereafter, Haiti’s electoral limbo became all the more acute.

The political developments in Port-au-Prince yesterday, then, show rare progress in the realm of Haitian political change.

The era of the embattled and ad hoc government led by Henry, whose resignation (which has now come to pass) was tied to the advent of this political transition, is over—sort of.

Michel Patrick Boisvert, who served as finance minister in Henry’s government, is the newly-installed interim prime minister. Boisvert will serve in this capacity “until the transition council appoints a new head of government, a cabinet and a provisional electoral council set to pave the way for an eventual vote.”

That Henry lost Washington’s political backing in recent months sped up the groundwork for the ongoing political transition, whose conditions and framing have a lot to do with the yeoman diplomatic efforts of the CARICOM bloc—of which Haiti is a member—to turn things around.

Whether this moment marks a turning point for Haiti, though, is an open question.

The gang-fueled unrest that has beset the country—hardening in place since earlier this year, when this latest crisis was triggered—reportedly continues. This serves as a reality check for the new, albeit, transitory powers that be.

They will likely not have an easy go of it, as they lean in on what hopefully is sustained engagement with a variety of stakeholders—in a purpose-driven manner, seized of the moment of opportunity, but also of peril.

CARICOM and the other key players will no doubt remain engaged in the process, not least because of previously agreed upon arrangements to do so.

This is one key to the hoped-for success of this new, particularly sensitive political era in Haiti.

The hopes of a beleaguered nation and its many backers, in the regional Community and wider international community, are riding on the transitional government’s success at prosecuting a relatively discrete mandate.

The politics involved in seeing a way forward give many pause, though, suggesting that—once again—the significance of this new political moment should not be overstated.

Given the gravity of the crisis currently facing Haiti, the discouraging reality that has befallen it, this is a time for all concerned to continue to put their shoulders to the wheel.

Haiti is not out of the woods yet; not by a long shot.

The bottom line is that the potential for things to go sideways is high, especially if the gang problem is allowed to fester and if political forces sacrifice the country’s renewed (and tentative) democratic march on the altar of power games.

Far from being chastened by the arrival on the political scene of the new government, transitory as it may be, the criminal armed gangs will likely play on the prevailing circumstances—against a backdrop where state authority has long been in collapse and they have increasingly “taken control as democracy withers.”

Those in authority, charged with putting things in place for a transition to electoral democracy, have little choice but to confront the ubiquity of gang influence in societal strata. It will be an uphill battle to wrest Haiti from the hands of gangs, who have historically been ensconced in the country’s political culture. But a third party’s pledge to render requisite assistance—in the wider context of security imperatives—is on the table.

Can these and other pertinent, pressing issues be managed well? We will have to wait and see.

The core question, though, remains the same as it always has regarding Haiti: Can those charged with such awesome responsibility as regards steering the future course of the world’s first Black Republic rise above the (political) fray, such that the country’s peoples can have a real chance to turn the tide in their quest for human and national development?

Absent an answer—to suit the times—to this question, the political upside of this moment will be fleeting.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.

The post Is Haiti’s New Transitional Government a Game Changer? appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post Chad Looks to Expel US Forces ahead of Polls appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The statement mirrors similar demands from Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, countries which are currently under military rule. All three have since followed through on their intentions to expel foreign forces. Chad is effectively the last country in the Sahel region that plays host to foreign soldiers. Niger, which was also home to US personnel, requested that the US withdraw its troops in March.

Chad is divided by the arid Sahara Desert to its far north, the tropical savannah to its south, and the Sahel transition zone between them. There are few notable geographic features besides Lake Chad, where the country gets its name. The capital N’Djamena lies near the Cameroonian border on the banks of the Chari River in the west. In the east lies the border region with Darfur in Sudan, to the north Libya, to the south the Central African Republic, and Niger and Nigeria to its west.

Chad has the third youngest population of any country in the world, at an average age of 16.6 years. It is a majority Sunni Muslim country, with a substantial Christian minority inhabiting the south. Most Chadians are secular on political issues, however.

After the death of former Chadian president Idriss Déby in 2021, the military initiated a coup that installed Déby’s son Mahamat. Since then, Mahamat Déby has moved to consolidate power. In 2022, he unilaterally extended the transition period, took up the reins of transitional president, and announced his candidacy for the presidential elections scheduled for May 6. Opposition candidates have had their candidacies rejected. The only candidate left with any hope of challenging Déby in the polls is the current prime minister, Succes Masra. However, Masra’s supportive statements toward the Mahamat Déby administration have tarnished his credibility as an opposition figure. The ultimate result of the upcoming elections will almost surely be a continuation of the present security policy, likely under a Mahamat Deby presidency.

Though only fielding around 30,000 soldiers, the Chadian military has received extensive support from foreign instructors and direct combat assistance. The country has been in a state of war for the better part of 30 years, with a civil war erupting in 2005. The military is battle-tested, not just from delivering the government a victory on the battlefield, but also from years of directly supporting regional militaries in their fight against Islamic extremists, with the 2012 Mali insurgency being one notable example.

Of growing concern to Washington is the potential alignment of Central and West African states like Chad with Russia, specifically through the Wagner Group, a Russian private military company. In an interview with France24, Déby insisted that his country was not a “slave looking to change his master,” suggesting a desire to balance the stakeholders involved. This accords with Chad’s longtime strategy of entertaining foreign backers to maintain a hold over an ethnically and politically fragmented society.

The pivot may be a tactical move by Mahamat Déby meant to boost his chances in the election. Goodwill towards France and the United States regarding their presence in Chad has run thin lately. By appearing to take a stance against historic colonial powers, Déby is galvanizing support from that section of the Chadian electorate.

Electoral politicking, however, may not be necessary. No Chadian election in history has ever been free and fair. Instead, commentators have suggested that it is a bargaining tactic that N’Djamena is using to increase US support for the Chadian government.

Chad’s relationship with France is deeper than France’s relationships with Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. As a result, Chad can’t shake the ties off so easily. For now, the French are not likely to immediately follow the Americans should the latter be fully expelled from the country.

The post Chad Looks to Expel US Forces ahead of Polls appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>The post The Gaza War and US-Caribbean Relations appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>This is apparent in a rising chorus of contrarian views in CARICOM member states’ Gaza war-related diplomatic narratives in the United Nations (UN), as compared to the United States’ associated positioning, setting the tone for the daylight between these states and Washington.

Initially, CARICOM adopted a position that was generally more restrained in tone. This was the context in which the bloc began to spend political capital on lending its voice to an already incendiary situation, striving for balance.

This behaviour on the international stage is consistent with the view of international relations scholars that, in international politics, smaller states inter alia “might seek [status-related] recognition by great powers, as useful allies, impartial arbiters, or contributors to systems maintenance” (emphasis added). Yet, in full view of Gazans’ disturbing reality and a region roiled by a metastasizing Gaza war, this type of diplomacy has its limits.

Several months later, in a Statement on the Ongoing Situation in Gaza, CARICOM leaders underscored that they are “deeply distressed” by the ‘deteriorating’ state of affairs in Gaza.” (In line with K. J. Holsti, who calls attention to the signal importance of such foreign policy actors in foreign policy decision-making, it is apt to unpack their pronouncements on the matter at hand.) While they reaffirmed their condemnation of Hamas’ October 7, 2023 assault on Israel and resultant hostage-taking, they pilloried subsequent “Israeli actions that violate international humanitarian law and the human rights of the Palestinian people.”

It is instructive that while US President Joe Biden eventually described Israel’s conduct of its war against Hamas in Gaza as “over the top,” this did not change Washington’s policy course in respect of support for Israel. Along the way, the U.S. repeatedly scuttled UN-related attempts to call for a ceasefire, tying the UN’s hands. This amid Israel’s apparent refutation of a humanitarian crisis in Gaza, in a context where UN-Israel relations have seemingly “reached an all-time low.”

In stark contrast, CARICOM leaders doubled down on unequivocally calling for “an immediate and unconditional ceasefire in Gaza and safe and unimpeded access for the delivery of adequate and sustained humanitarian assistance.” That said, Jamaica’s Gaza war-related voting record in the UN General Assembly and public pronouncements have caused some consternation among commentators; and Prime Minister Andrew Holness had to set the record straight.

CARICOM leaders also contended that, for the regional grouping, Israel’s excesses in the occupied West Bank contribute to international instability. They tied their criticism of Israel’s wanton disregard of calls from within UN bodies for a ceasefire to the provisional measures-related order in the South Africa v. Israel case at the International Court of Justice.

And they did not pull punches when advocating for a two-state solution in keeping with UNSC Resolution 242.

The bloc continues to raise the alarm over this conflict in the Middle East, citing concerns regarding the wider implications for “regional stability and international peace.”

The normative character of CARICOM’s foreign policy approach is apparent in its Gaza war-related diplomatic trajectory, which is also illustrative of a cumulative tension vis-à-vis the United States’ imprint on the said conflict. This is because the United States’ foreign policy intentions qua state behaviour, in the Middle East and elsewhere, hinge on power.

For its part, Guyana has signalled its impatience with Washington’s Israel policy which, for some scholars, centres on a “special relationship”— one that purportedly plays an outsized role in “the totality of American foreign policy in the Middle East.”

Notably, Guyana abstained from a recent, widely criticized US-led draft resolution in the 15-member UN Security Council (UNSC). Guyana was elected in 2023 to join this UN body, for a two-year term (2024-2025), as a non-permanent member. That measure set a low bar. It just made the case for the imperative of an ‘immediate and sustained ceasefire’ in Gaza, compelling Guyana to underscore that the resolution stopped short of aligning with the international community’s call for an immediate humanitarian ceasefire in Gaza.

Russia and China, two of the UNSC’s five permanent members, voted against the draft resolution. It failed to pass, given the strictures of the UNSC voting system.

Guyana was among the 14 UNSC members which, shortly thereafter, backed another resolution. On this occasion, there was a clarion call qua demand for ‘an immediate ceasefire’ during Ramadan in 2024. The Security Council passed the resolution, with the U.S. conspicuously exercising an abstention regarding the vote-related proceedings.

This only served to further highlight Washington’s growing international isolation regarding foreign policymaking in the face of the decades-old Israeli-Palestinian conflict which, for months now having passed into uncharted waters, has been centre stage in international politics—eclipsing even the Ukraine war.

That the United States is haemorrhaging prestige in the Caribbean has not ceased either. This has ruffled feathers there in this geopolitical moment, putting the most significant strain on US-CARICOM relations since their post-Trump era revamp. No sooner had these relations benefitted from a reset under the Biden administration than have the last few months marked a stress point in those ties, which must be gauged anyway by their historically “mixed success.”

One source of things changing is that as postcolonial states, which are products of the struggle for political independence, CARICOM member states increasingly view the Gaza war through a normative qua ethical prism. In turn, it is a mirror onto their own quest for autonomy and unwavering belief in self-determination. (The fact is that these states’ postcolonial identities anchor their worldview, which is shaped inter alia by legacies of colonialism and the plight of those peoples who are still oppressed.)

Today, countries like Guyana turn to UN bodies like the UNSC to shore up diplomatic positioning in that regard.

In this thinking, all such peoples have a right to self-determination among the community of nations.

Washington’s decidedly skewed Gaza war-related foreign policymaking challenges such postcolonial conceptions anew, having a bearing on these states’ perceptions of their own status in the international system.

This a watershed moment, then, in the sense that coming into focus for CARICOM—indeed, shaping its view of Washington—is how the U.S. will earnestly respond to the international community’s outcry about the devastation wrought by six-plus months of war in Gaza and the ever worsening plight of its peoples.

Reports are Washington has put Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on notice that unless his government changes its war strategy, which has stoked the humanitarian crisis in that enclave, it might have to reassess facets of its Israel policy.

Just recently, though, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a legislative package that provides tens of billions of dollars in security assistance—among others—to Israel. The Senate has since passed the bill. And Iran’s recent direct airborne attack on Israel only galvanized US support for the latter, with this great-power rallying to Israel’s defence.

The question is whether such support emboldens Netanyahu to toe the maximalist line of far-right elements in his government by continuing to wage Israel’s war on Gaza—which, according to some analysts, possibly constitutes a never-ending war with ulterior motives. That Netanyahu now openly scoffs at international pressure for a Palestinian state says it all. This against a backdrop where, even if Netanyahu’s days in government are numbered, “his approach to the war [qua ‘use of force’ per defence establishment thinking on Israel’s National Security Doctrine] has broader support.”

The prevailing cosmopolitan view, which stands in opposition to the Netanyahu government’s position on the matter, is for a two-state solution to come to pass—as the only way to end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

In a further sign of the (geopolitical) times, though, the UNSC failed to recommend full UN membership for the State of Palestine, owing to the United States’ casting a veto regarding the draft resolution in question.

Guyana was among the 12 UNSC members which voted in favour of the draft resolution, which reads:

“The Security Council, having examined the application of the State of Palestine for admission to the United Nations (S/2011/592), recommends to the General Assembly that the State of Palestine be admitted to membership in the United Nations.”

This draft resolution will go down in the annals of UN-anchored multilateral diplomacy as having produced an important moment for a show of support for Palestine, in what is perhaps Gaza’s darkest hour. It faces unprecedented, horrific destruction.

With the international spotlight on the diplomatic moment personified by the aforesaid UNSC vote, on April 19, 2024, Barbados announced its official recognition of Palestine as a State. Considering its timing, this move is likely intended (at least in part) as a rebuke of the United States’ reasoning behind its vote-related stand.

A few days later, the Government of Jamaica indicated that it took the decision to recognize the State of Palestine. In shedding light on this decision, Senator the Honourable Kamina Johnson Smith, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade, called attention to Jamaica’s support for a two-state solution. Minister Johnson Smith said that this is the “only viable option to resolve the longstanding conflict, guarantee the security of Israel and uphold the dignity and rights of Palestinians.” Furthermore, she underscored: “By recognizing the State of Palestine, Jamaica strengthens its advocacy towards a peaceful solution.”

Minister Johnson Smith noted that her country’s decision to recognize the State of Palestine is in keeping with its “strong commitment to the principles of the Charter of the United Nations, which seek to engender mutual respect and peaceful co-existence among states, as well as the recognition of the right of peoples to self- determination.” She also linked the decision to the Gaza war and the resultant humanitarian crisis, reaffirming inter alia Jamaica’s backing of an immediate ceasefire.

Barbados and Jamaica have cast their lot with the 10 other CARICOM member states which have recognized the State of Palestine. They are St. Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Haiti, Grenada, Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Belize, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, and Guyana.

Behind the scenes, CARICOM leaders and diplomats have likely (and in no uncertain terms) voiced their misgivings to their American counterparts as regards Washington’s approach to treating escalating tensions in the Middle East. The matter of the groundswell of support in CARICOM for an independent Palestinian State and for it to be afforded all attendant rights have surely come up, too, especially at a time when more countries are prioritizing recognition of that state.

Insofar as it is “embroiled in [the] Gaza conflict,” Washington is regularly in touch with Caribbean capitals. In an attempt to drum up support for what some analysts view as its one-dimensional determinism in foreign policymaking, Washington makes the rounds of these capitals.

This as the influence of the People’s Republic of China—which, along with Russia, is the United States’ strategic competitor—grows in the Caribbean.

To varying degrees—with a healthy respect for long-standing, country-level ties and the record of accomplishment—respective emissaries carry on with the daily business of diplomacy. Having regard to the deep “security and economic ties” between the U.S. and CARICOM, it is also the case that the latter grouping would not lose sight of the importance of the long game in its member states’ respective foreign policy approaches to America.

Still, attuned to their postcolonial identities, CARICOM member states are guarded in this moment. After all, their foreign policy inclination is to embrace “human and global interest.”

Such conviction is side stepped by others—if not rhetorically, then in praxis. For them, the competitive nature of the putative zero-sum international system is such that their own security is the overriding concern.

As CARICOM member states take stock of their contribution to the international community’s contemporary diplomatic manoeuvres on the question of Palestine, they are of the mind that they stand on the right side of history.

Yet for all their attention to the normative grounds for defusing the powder keg that is today’s Middle East, leaning in on the case for approaching the national interest in the same vein, CARICOM members run up against the broader context of their foreign policymaking. Simply put, à la the system-level, international relations are “geopolitically constructed.” This framing is the proximate cause of the Gaza war; but, it is not the only factor that one ought to assess. As already intimated, domestic and “unit-level factors” in foreign policymaking also play a consequential role in the grand scheme of things.

In this schema, it is highly debatable whether the top dogs seriously weigh moral ends.

In standing on principle, strengthening its status-related hand in international politics, CARICOM has notched another victory in the thrust-and-parry of the anarchic global system.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author(s) alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.

The post The Gaza War and US-Caribbean Relations appeared first on Geopolitical Monitor.

]]>