Summary

Negotiations at the Copenhagen climate change summit have been long on drama and short on prospects for a feasible end result.

Analysis

The task of putting together a successor to the Kyoto Protocol is nothing short of herculean. On one side, there are the developing countries who don’t want to be saddled with any burden that would compromise their economic rise. On the other, there are the developed countries who don’t want to cripple their ability to compete in the global economy. Both sides are purportedly interested in an agreement that passes the scientific litmus test. That is, an agreement with deep enough cuts to avert the disastrous scenarios envisioned by climatologists. These questions are looming over the hundreds of delegations that are currently locked in negotiations at Copenhagen.

A proposal that has developed countries paying large sums of money to developing countries to help them cope with climate change has emerged as a threat to the summit’s success. The size of this UN-administered climate change fund has been hotly debated. Britain’s original proposal presented a figure of $10 billion per annum through 2012-2015, but the sum being floating by developing countries is more in the neighborhood of $400 billion per annum by 2020.

Even the medium figure of $200 billion per annum would be hard to envision working. Owing to global recession, military spending, and social programs, developed countries aren’t particularly cash-rich. If developed countries were somehow immune to the effects of climate change, then it may be possible to allocate the funds. But this is not the case. If sea levels were to rise 1.4 meters, $100 billion worth of property would be jeopardized along the California coast alone. The law of democratic politics dictates that any leader prioritizing international over domestic flood protection will find that their tenure is a short one.

Ironically it is the BRIC countries that are in more of a cash-rich position. China currently holds currency reserves of over $2 trillion.

Paying high levels of ‘reparations’ is sure to be politically divisive to say the least in the developed world, making its’ inclusion in the final treaty a potential deal-breaker, particularly for the United States.

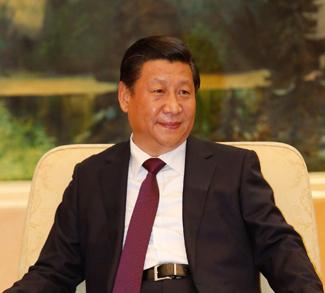

Although Chinese negotiators are well aware that such a high figure is unpalatable for developed countries, they will continue to drive a hard bargain. By keeping up with this demand, China can hope to further codify the disproportionate responsibility between developed and developing world in tackling climate change.

Whether or not China would receive any climate fund money is still unclear and the topic of heated debate between the Chinese and American delegations on Thursday. What is clear, however, is that Beijing wouldn’t be paying into the fund.

Even if Chinese insistence over ‘reparation’ scuttles any hope of agreement at Copenhagen, the Kyoto Protocol will survive the summit- a point recently emphasized by executive secretary of the U.N Framework Convention on Climate Change Yvo de Boer. Falling back on Kyoto would also serves Chinese interests, as Beijing could remain exempt from legally binding targets, allowing it to comfortably set its’ own goals and serve as its’ own verification mechanism.

The only scenario that China needs to worry about is becoming isolated and publically branded with the label of obstructionist. So far, it seems that the close Sino-Indian negotiating stance will ensure that this doesn’t come to pass.

There are however cracks emerging in developing world solidarity. On Wednesday, Tuvalu introduced a protocol proposing deep cuts across the board for developed and developing countries alike. Tuvalu was supported by several islands and African states but opposed by the BRIC countries in China and India, among others.

There can be no legitimate final deal without agreement between the United States, the EU, and BRIC countries. President Obama, leader of a state that didn’t even ratify the Kyoto Protocol, will not acquiesce to large-scale ‘reparations’, especially when developing countries refuse to commit to a deep and verifiable reduction target. China, on the other hand, will continue to place an extremely high premium on unhindered economic development as a way to legitimize the benefits of one-party rule.

While the original assumption was that the pre-summit targets announced by the China and India signified their commitment to hammer out a deal at Copenhagen, it now seems more likely that it was pre-emptive saving face for failing to agree on a new global climate change treaty.